When I first told people I was working on a comic about trauma, I sometimes got funny looks. I can’t be certain, but I think the correct translation of this type of body language would be something like this: “Why are you doing a comic about that? Aren’t comic books supposed to be silly, or surreal, or written for young adults?”

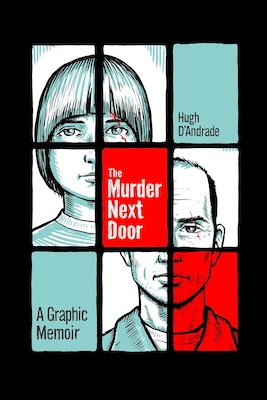

My book is called The Murder Next Door: A Graphic Memoir, and it concerns the murder of my next-door neighbor when I was a child, and the ways that this event has impacted me throughout my life. Working on this book involved drawing on certain memories that were painful to recall. At times I had to stop working, either to break down sobbing, or to just stare at the wall in numb silence.

I sometimes joke that the process was healing, since it allowed me transform trauma into boredom, thanks to the long hours and tedious work that is involved in any work of graphic literature. But truthfully it did provide me with a lot of time to think about my memories, and what it means to both draw and write about trauma.

The skeptical reactions that my friends had to my chosen topic is understandable, but a little misplaced. The list of graphic novels about trauma is a long and distinguished one—in fact, trauma might be one of the core subjects of this type of literature! Here’s why:

Our minds encode traumatic experiences as images, but they may not always be the most coherent images. A survivor may recall only flashes of imagery, appearing out of order, shorn of context. I believe this happens because the mind wants to etch the experience into our consciousness in indelible ink (so that we can avoid danger in the future), while also scrambling the information, to protect us from overwhelming anxiety.

And this is where comics are so ideal. When you, as a reader, pick up a comic book or graphic novel, you’re encountering a collection of images—hundreds of frames, sometimes confusing or chaotic. As you read, in your mind’s eye these images are threaded together, woven into a new meaning, and assembled into a coherent narrative.

This process mirrors what the mind does, or needs to do, to manage traumatic memories! So, I believe that comics are a natural forum for addressing trauma, because of the way they mirror our minds’ process of encoding and re-encoding memory. The comic artist Seth called comics “memory machines.” And it is memory that is the most needed, but sometimes the most fugitive, when something terrible happens.

Below is a list of powerful graphic novels that address trauma. I highly recommend all of them.

Come Home, Indio by Jim Terry

This book, by an absolute master of the comics medium, depicts what I might call “ordinary trauma.” A person need not be a victim of some spectacular violent crime to experience trauma; sometimes, all it takes is being born as a person of color in a racist society. Or, too, being born into a family of addicts, in a society that profits from addiction.

In this book, Jim Terry beautifully describes growing up as an indigenous person, evoking his family life with love, tenderness, and raw anger. As a child, he is exposed to racism from the very start, while also suffering the indifference and sometimes hostility of adults. Addiction is part of the fabric of this life, and he faces its effects — and the process of overcoming it — with heartbreaking honesty.

Did I mention that Terry is a master of this art form? Pick up this book to see what the language of comics can do in the hands of someone who has true control of his brush, who loves language and pictures, and who knows how to make black and white lines come alive.

Epileptic by David B.

This book is another example of “ordinary trauma.” As a child, young David has a comfortable home life in France, and he is lucky enough to possess a precocious talent for art. But his childhood is plagued by the turmoil and turbulence of his brother’s epilepsy, which can turn an ordinary day into a nightmare of violent seizures and tedious hospital visits. He is faced with dueling feelings that would confuse and

trouble any child or adult: love for his brother, as well as resentment at the way his brother’s ailments can deprive David of love and attention he also deserves.

The artwork in this book is inspiring, and entirely unique. Images are drawn with a confident hand, using a heavy black line that can sometimes describe incredible detail, and sometimes allow for pure simplicity. At times, the images spill and spin across the page, with a dreamlike effect. There are very few books that evoke the inner lives of children with so much honesty. (Note: this book is a few decades old, and may be difficult to find in some comic shops, but is easily found online.)

The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui

One trauma that is all too common in our world is the trauma of dislocation experienced by immigrants and refugees. Thi Bui and her family immigrated from Vietnam to the US, in the 1970s, following that terrible war. This book is the result of her efforts to reconstruct her family’s history from her own memories and the memories of her parents.

The Best We Could Do beautifully depicts intergenerational trauma. As her parents describe the many different forms of oppression and colonization the Vietnamese people have suffered over the decades and centuries, you can see how suffering is passed down from generation to generation, but also the ways that love and hope are shared as well.

Maus by Art Spiegelman

I’m a bit hesitant to list this book because of its fame and status. For many people, this is the only graphic novel they have ever read. It is probably the first graphic novel to gain mainstream literary acceptance in this country. That said, there are still far too many people who have never read it, or never heard of it, and don’t know what they are missing! I’ll suggest this book for those readers, since it really is essential reading for anyone who cares about the ways that people survive history.

Spiegelman describes in painstaking detail the struggles of his Jewish parents in Poland under Nazi rule. The suffering they endure is immense, and the author gives us an up-close view of how their lives were upended, their communities and families destroyed, and how they managed to survive. But he is equally honest, and equally detailed, in describing the ongoing suffering that he endured, as a relatively privileged child of two survivors, growing up in America. He uses tiny pictures to show his readers how trauma never really goes away. It remains in our minds, in our families and homes, waiting to be uncovered, offering us lessons, if only we can begin to listen.

Look Again by Elizabeth Trembley

I was given this book by a mentor who suggested I might find it interesting, since the themes of this book were so similar to my own. They were right! Trembley tells the story of her encounter with a dead body in the course of an ordinary day, and the immense impact this experience had on her. Just as I described earlier, the encounter left her with fractured images, flashes of memory, that she later worked to thread together into a coherent narrative. In describing the experience, she tells the story several times, each time with a slightly different emphasis, or slightly different details. The meaning shifts, and becomes richer, but doesn’t really change. And this is so much what it’s like to face a traumatic experience: it has to be peeled back, layer by layer, like an onion, to uncover the meaning, and to find the narrative. This is a wonderful book, and very well informed by the latest psychological theories of trauma.

The Diary of a Teenage Girl by Phoebe Gloeckner

Although this book is fictional, it closely tracks with Gloeckner’s autobiographical comic work, collected in another book titled “A Child’s Life.” It tells the story of Minnie, a young girl growing up in San Francisco in the 1970s—experiencing sexual abuse by her stepfather, drug use, and prostitution. The story is told with a combination of comics pages, diary entries, and illustration, and it showcases the cartooning talents of a person who has been drawing comics since childhood, and who also works as a professional illustrator of medical textbooks. One thing this book addresses is the ambivalence a victim can sometimes feel towards their abuser. Minnie’s stepfather is portrayed as a creep and a predator, but we see that Minnie’s emotional response is complex: she’s angry and hurt by the abuse, but by the end of the book, we see her taking back some of her power. And in her final encounter with her stepfather, we see that see feels some pity and disdain for him. This book may be fiction, but it holds a lot of truth.

Silence, Full Stop by Karina Shor

If I’m right that trauma is often experienced as random flashes of imagery, and that comics as a medium can sometimes mirror the process of recovery, by showing us how the mind can create coherence out of disconnected images, well then, this book is a prime example.

The trauma in the case of this author’s experience is multiple: there is the trauma of the child suffering dislocation through immigration; the trauma of the “outsider”; there is the trauma of addiction; of an eating disorder; and finally there is the trauma of sexual abuse. This book describes it all, with brutal honesty and stunning artwork.

It’s a tribute to the author’s abilities that we know it’s coming, even before the truth arrives. There’s a dread, an anxiety, that she communicates perfectly. The suffering she describes is real, but so is the empathy that we, as her readers, feel for her.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.