When most folks hear the word “archive,” they picture a dusty library folder…but when scholars use the word, sometimes they mean it in a different sense. For them, “the Black Archive” certainly refers to the papers and documents that track lives and deeds. But scholars, or at least new generations of scholars and writers, also see it as something messier and more imaginary. You don’t necessarily go to a library and pull up a call number for a file with this kind of archive. Instead, you ask impossible questions: How do we remember, much less reckon with, ugly truths that entire civilizations tried to bury? How do we find stories that aren’t in census data or the letters of rich folks? Where is the archive of the diminished, the despised, the dispossessed?

Fortunately, we live in a marvelous time for solving historical mysteries. Thanks to tireless digging and creative approaches (often using digital tools such as the new databases of scanned newspapers but also using the words of poets when historians alone reach for facts and language), we have a cluster of books that model new ways to see not just Black history but also American history, with all of its beauty and cruelty, afresh.

The Black Archive is having a moment now, and here are 7 books to intrigue, confound and enlighten you—all with stunning stories of courage and love.

The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts: The True Story of The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Gregg Hecimovich (with a foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.)

Some two decades ago, The Bondswoman’s Narrative became one of the remarkable and strange best sellers of the 21st century. Written by Hannah Crafts in the 1850s, this handwritten manuscript was identified by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. as the first known novel written by an African American woman. With its strange gothic horror melded with suspense, and sometimes sentimentalized and sometimes brutally matter-of-fact depictions of the pain, sexual violence, and resilience its heroine used to reveal her captors’ lies and to survive bondage in the antebellum south, The Bondswoman’s Tale was a major contribution to the annals of American literature. And yet, it also posed a literary mystery that hit the headlines: Who was Hannah Crafts? Was she Black? White? How had she escaped? Was this book a fraud? What was her real story?

Thanks to indomitable detective work married to incisive and generous literary analysis, Hecimovich has brought to life a story that simply couldn’t have existed without decades of determination, expert sleuthing, and some luck. As his book reveals, her true name was Hannah Bond, an enslaved Black woman from North Carolina who escaped disguised as a man and fled to a farm in upstate New York. While in hiding, she wrote A Bondswoman’s Tale, which, although a work of fiction, was filled with clues about who she was and what her own actual experiences had been.

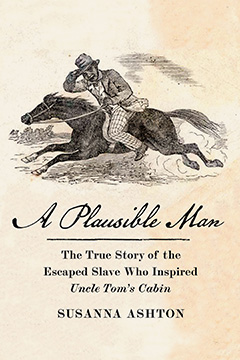

Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom by Ilyon Woo

First off, props to such a compelling title. The Crafts’ story is well known to scholars, but Woo’s fresh retelling of their tale is riveting. Step by step, she tracks how Ellen and William Craft, an enslaved couple in Georgia whose union was not recognized by any court of law at that time, maneuvered one of the most audacious escapes imaginable. Light-skinned Ellen disguised herself as a genteel white man in poor health, traveling North for treatment with his dark-skinned slave—her husband, William, in disguise as her captive. Hiding in plain sight, the couple braved inquisitive hotel guests and pushy railway passengers. Ellen even put her arm in a sling to justify avoiding hotel desk registries—as she was illiterate and would have been found out when presented with a pen.

Once north in New England, the Crafts’ troubles were not over: they had to evade recapture and make their way to Canada, and eventually, now facing international celebrity status, they found an uneasy sanctuary in England. The Crafts’ ambitions were often at odds with the aims of the Anti-Slavery organizations and white patrons they were surrounded by. And sometimes, their wishes were not in concert with those of their activist friends, such as fellow fugitive William Wells Brown, who sought to keep them in the public eye even when they were hoping to settle down more quietly. But the couple held onto each other, and in an astonishing twist rarely seen in such life stories, they boldly chose to return to Georgia some years after the Civil War. Woo lets their story unfold in their own words at times, drawing from their memoirs and interviews. But she also builds out their story in the broader context and conversations around fugitivity and freedom. Taut and tense, Master Slave Husband Wife is a story of flipping gender, race, and power politics upside-down in the pursuit of freedom fueled by love.

Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge by Erica Armstrong Dunbar

News flash: George Washington not only held people in bondage, but he and his wife were mad about it. They found managing enslaved people tiresome, although well worthwhile. Hence, it should have been no surprise to anyone that they bitterly complained about, chased, harassed, and did their best to terrorize Ona Judge, a brave and resourceful woman who walked out their door one day never to return.

In this gem of a book from 2017, Erica Armstrong Dunbar traces how Ona Judge foiled the plans of the Washingtons, who used all their connections and political heft to recapture her.

During that stretch of time when Philadelphia was the capital (1790—1800), the Washingtons lived there with eight enslaved people to wait on them. This was all very comfortable for the Washingtons, but local Pennsylvania laws meant that after six months, those slaves were supposed to be freed. After all, this wasn’t the slave state of nearby Virginia. The Washingtons tried to circumvent these laws by sending their enslaved servants in a regular rotation back to Virginia just before the six-month mark. Ona Judge, learning that she was due to be sent back to Mount Vernon, had other ideas. The ensuing hunt that Dunbar sketches out for us is suspenseful and undergirded by a deep terror—Judge’s very survival was at stake. At stake, too, as the author shows us, is our own willingness to reckon with the myths and truths of the founding fathers. Any romantic notions of George Washington will be shook.

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tiya Miles

A sack? A book about a bag? What can we learn from looking at a particular object, in this case, a small cotton bag filled with tokens of love for 9-year-old Ashley, a child about to be sold away from her family? According to the embroidered message sewn onto the bag a generation later, the sack contained only a tattered dress, three “handfuls” of pecans, and a braid of Ashley’s mother’s hair. But it carried far more than that—it was, in the words of the mother, “To be filled with my love always.” With imaginative archival work that goes far beyond letters, documents, or even genealogy, Miles builds out a tender and loving world of mothers and daughters with these simplest of objects.

Where other writers might be confounded or frozen when confronting the unknown, Miles admits that she is never able to precisely able to identify Ashley and her mother, but doesn’t let that stand in her way of seeking broader truths. Paperwork files aren’t the only place for stories. Examining every word in the embroidered message, Miles finds legacies of survival in textiles, in seeds, and in hair that connect traditions and longing. There is so much urgency in this work—it calls us to see things that have been discarded for what they are and what they can be.

Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America by W. Caleb McDaniel

From the title of this winner of the Pulitzer Prize in History, you’d think you’re going to read a powerful story about reparations of some sort. And for sure, that’s what it is. But be ready: it lands in places you won’t see coming. Henrietta Wood was born enslaved but in 1848, in Ohio, she was legally freed and thought her days of bondage were over. In 1853, after a few brief sweet years of freedom, though, she was kidnapped by a Sheriff named Zubulon Ward, dragged over the border into Kentucky, and sold back into bondage. She wasn’t free again until after the Civil War. This kind of tale could have been buried forever and no one would have remembered her particular tragedy. But Wood wasn’t going to let this injustice go by. She didn’t forget, and she didn’t forgive. With a sharp eye for detail and a rich historical framing that highlights the compassion and dignity of the remarkable woman at the core of the story, McDaniel tells how Wood went on to sue Ward for damages and won not only a moral victory but also a substantial financial one and one which was to set the stage and standard of restitution thereafter. That standard has rarely been upheld, but thanks to McDaniel’s resurrection of the story, we can see how reparations, no matter how meager meant something powerful to the survivors.

The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots: A True Story of Slavery; A Rediscovered Narrative, with a Full Biography edited by Jonathan D. S. Schroeder.

Oooooh kay. As you can tell from the harrowing title, there is nothing subtle here. John Swanson Jacobs escaped enslavement in the American South. He was then determined to use his freedom to wage war against the avarice of the American system and its supporters—especially the 600,000 enslavers. But he wasn’t going to be dull about it! He would take everything down with a righteous fury that wouldn’t be mediated, filtered or softened by a white abolitionist editor, as was often the case for life writing by survivors of bondage. As he wrote: “My father taught me to hate slavery: but forgot to teach me how to conceal my hatred.”

In Jacob’s memoir, which is accompanied by a biography by Jonathan D. S. Schroeder, who unearthed the original version from an 1855 newspaper, Jacobs decides to go for broke. His writing is wry, unforgiving, and full of fury. It’s hard to take your eyes off the page. While this is certainly the story of his life in captivity and his later escape, it chronicles, too, the racism and cruel disdain he often encountered in the North. He takes time out of his own riveting experiences (carrying pistols to use against “fleshmongers” or bounty hunters, for example) to rail against the hypocrisy of the founding political documents of the United States. To Jacobs, the American Constitution, which enshrined slavery, was “that devil in sheepskin.”

Jacobs told his story from afar—from Australia, in fact—and perhaps that’s why he could be so brutally candid. Back when he was enslaved, he had accompanied his enslaver to the northern states. Rather than return south, Jacobs fled to stay North on his own, free terms. After a few years, he became a mariner. His voyages took him around the globe, and during a stint in Australia in the mid-1850s, he published his life experiences in a newspaper. A softer and much-truncated version of his memoir came out in book form a few years later. This full and uncensored version from the newspaper, though, newly brought to our attention in this edition by Schroeder, of what slavery was and what it meant to Jacobs was essentially lost on the other side of the globe until now.

Jacobs’ raging tale of survival and resilience would be wild enough. Yet the work has another stunning twist: John Swanson Jacobs was the brother of Harriet Jacobs, a woman who had herself escaped intolerable suffering at the hands of the Wheeler family with an almost incomprehensible strategy: she hid in an attic crawlspace for seven years. Yes. You read that correctly. Harriet, too, eventually escaped from enslavement and from that attic by making it North. She went on to write what is probably the most influential account of enslavement from a woman’s perspective, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

John and Harriet were a powerful pair of siblings, with a shared gift for bold storytelling and uncompromising courage. How wild is it to see a story of bondage and freedom from both a brother and sister who vowed never to let their suffering be forgotten? Instead, with these astounding memoirs, they lay waste to a system that had tried to crush them. Teamwork.

The 1619 Project created by Nikole Hannah-Jones

There’s so much to be said and has already been said about The 1619 Project that it’s hard to remember that beyond the drama and the conversations about banning it from schools or libraries, it is something to simply read and reckon with. Although originating as a special issue and multimedia project for the New York Times Magazine, designed to mark the first arrival of enslaved people to North America, the book compilation is stranger and provocative in its very structure—the breadth of its goals are more readily apparent in book form. The 1619 Project is a tremendous expansion of the original endeavor, but it isn’t just longer and broader in its considerations of topics, approaches and responses to some of the backlashes it has received. It’s more interesting than that. Controversies over the arguments put forth by the project have rarely looked at the art (written and visual) that the team offers up as a gloss to explicate the sometimes spotty history that was designed to occlude Black people from hindsight.

Hannah-Jones and her team have created a new origin story for the country by showcasing factual history, to be sure, but this volume is richly framed with the work of poets and artists. Some of the facts of American history leave you speechless. It may only be the artists who can fill in the gaps of a history designed to silence and suppress.

The 17 essays are themselves consistent in arguing with dogged and punchy care about how slavery has been and continues to be at the core of what defines the United States. Indeed, some of the most powerful essays are often the ones you don’t see coming…there is Kevin Kruse on “Traffic,” for instance, or Anthea Butler on “Church,” wielding as much insight as the more predictably polemical essays such as that of Ibram X. Kendi on “Progress,” Jamelle Bouie on “Politics,” or Martha S. Jones on “Citizenship.” But this volume is worth checking out for more than just its formal conversations. Cognizant of the restraints of the essay form, the project includes the work of poets and fiction writers that intersperse each essay and reminds us that archival documents are a legacy of limitations. It takes Clint Smith, Claudia Rankine, Sonia Sanchez, Rita Dove, Darryl Pinckney, and Jesmyn Ward, among many other artists, to respond to the archival truths in their most stark and human terms.

After an essay on “Capitalism” by Matthew Desmond, an interspersed page in the middle of the book, for example, posts a paragraph about the 1816 attack by US troops on a British military site in Florida, Fort Mose, known as the “Negro Fort,” a stronghold of free Black people and fugitives from slavery. The attack, which led to the conquest of Florida, meant that the region could no longer be a destination for those heading South seeking freedom from bondage. These unlucky freedom seekers could be claimed, again, as property. The poem that immediately follows, however, Fort Mose by Tyehimba, Jess, walks us through this history anew and limns notions of property and capital that the essay can only gesture towards: “They fought only/ for America to let them be/ marooned-left alone-/in their own unchained,/singing,/worthy,/blood

After an essay by Leslie and Michelle Alexander on “Fear” and an interspersed page noting that the famed free Black mathematician and scientist Benjamin Banneker wrote to Thomas Jefferson pointing out how the institution of slavery contradicted the fine points trumped in the Declaration of Independence, is a poem, “Other Persons” by Reginald Dwayne Betts. Betts incorporates the language of the constitution, particularly the 3/5ths clause that famously counted enslaved Black and native people as only 3/5ths of a white person in terms of apportioned political representation. As the poet rephrased it: “Slavery, another word for slavery, is a fraction.”

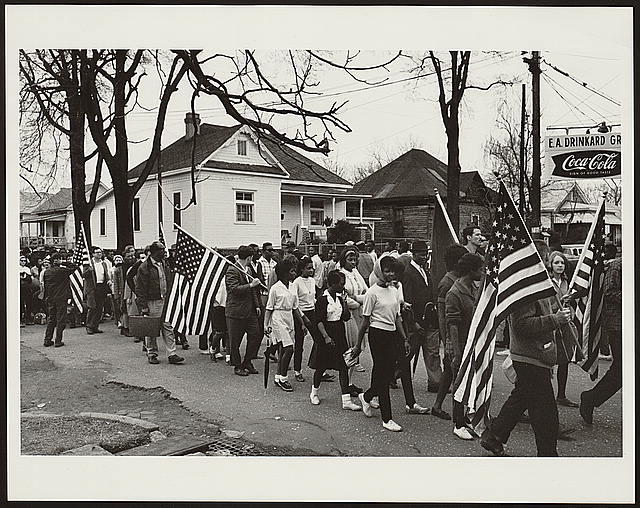

With creative responses to each essay and wry or poignant black-and-white photographs to launch each unit, The 1619 Project reminds us to reach further and with the courage to new kinds of documents and methodologies to find buried truths.

That’s not to say that the 17 essays aren’t profoundly grounded in accepted and vetted historical facts. They are. And it’s not to suggest that they aren’t accessible—they were shaped for a general readership and are kind and generous in how they reach out to readers to bring them along some difficult terrain. Nonetheless, by weaving art and scholarship, this compilation offers us new paths to reckon with truths and move forward in informed and impassioned power. As much as the historical work and public facing journalism lays it out for readers, the art within The 1619 Project suggests that it just might take our poets to model the tools we need to understand what has led us here and where we all have to go.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.