Alvin F. Poussaint, a psychiatrist who, after providing medical care to the civil rights movement in 1960s Mississippi, went on to play a leading role in debates about Black culture and politics in the 1980s and ’90s through his research on the effects of racism on Black mental health, died on Monday at his home in Chestnut Hill, Mass. He was 90.

His wife, Tina Young Poussaint, confirmed the death.

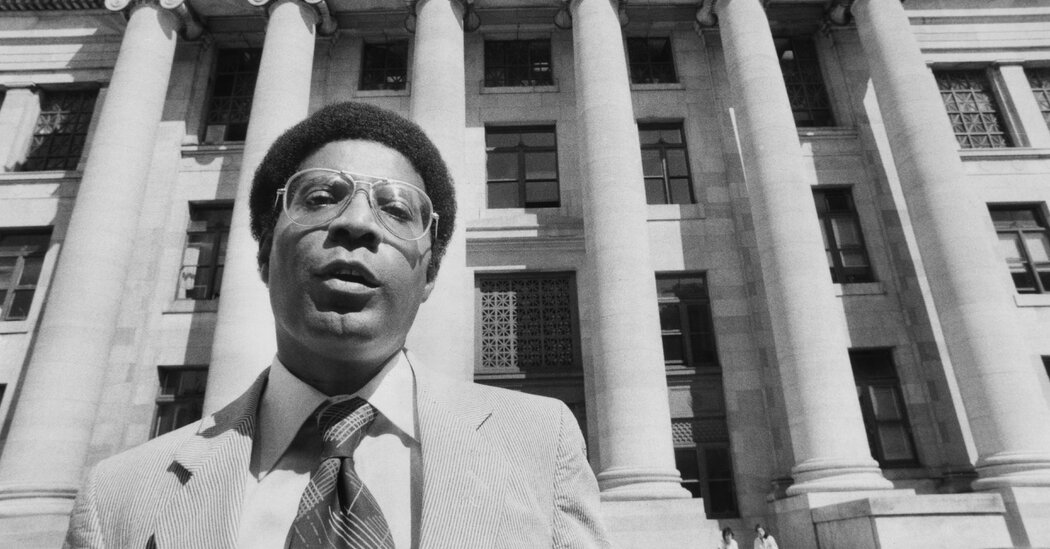

Dr. Poussaint, who spent most of his career as a professor and associate dean at Harvard Medical School, first came to public prominence in the late 1970s, as the energy and optimism of the civil rights movement were giving way to white backlash and a skepticism about the possibility of Black progress in a white-dominated society.

In books like “Why Blacks Kill Blacks” (1972) and “Black Child Care” (1975), he walked a line between those on the left who blamed persistent racism for the ills confronting Black America and those on the right who said that, after the civil rights era, it was up to Black people to take responsibility for their own lives.

Through extensive research and jargon-free prose, Dr. Poussaint (pronounced pooh-SAHNT) recognized the continued impact of systemic racism while also calling for Black Americans to embrace personal responsibility and traditional family structures.

That position, as well as his polished charisma, made him a force in Black politics and culture. He served as Massachusetts co-chairman for Reverend Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign and was reportedly the model for Dr. Cliff Huxtable on Mr. Cosby’s sitcom “The Cosby Show.”

He repeatedly denied being Mr. Cosby’s inspiration, but he certainly was Mr. Cosby’s guiding light. He read almost every script as a consultant for the show, he said, sending notes about how to avoid stereotypes or deepen a story line and advising writers before they tackled a particularly thorny theme.

“I don’t rewrite,” Dr. Poussaint told The Philadelphia Daily News in 1985, “but I indicate what makes sense, what’s off, what’s too inconsistent with reality.”

Long before Mr. Cosby was accused by more than 50 women of sexual assault and misconduct, he was known as America’s Dad, a stern but loving paterfamilias of not just the Huxtable clan but also America at large. Much of the advice Huxtable gave to Black youth mirrored what Dr. Poussaint had been saying for years. (There is no evidence that Dr. Poussaint knew about the accusations against Mr. Cosby.)

Dr. Poussaint became a go-to commentator for journalists looking for insight into Black culture. When “Family Matters,” another sitcom centered on a Black family, featured a brainy, goofy teenager named Steve Urkel, Dr. Poussaint was on the case.

“The fact that he’s a nerd and very bright may be a step forward,” he told The New York Times in 1991, “accepting that a Black kid can be bright and precocious and might end up in an Ivy League school.”

Dr. Poussaint consulted for both “The Cosby Show,” which ran from 1984 to 1992, and its spinoff, “A Different World,” which aired from 1987 to 1993. He wrote the introduction and afterword to Mr. Cosby’s 1986 best seller, “Fatherhood”; the two then co-wrote “Come On, People: On the Path From Victims to Victors” (2007).

By the time “Come On, People” was published, Dr. Poussaint had grown concerned about Black men, particularly young ones. His older brother, Kenneth, had spent years in and out of jail, drug rehab and mental-health institutions, a tragedy that Dr. Poussaint saw as equal parts personal and social.

With the journalist Amy Alexander, he wrote “Lay My Burden Down: Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis Among African-Americans” (2000), and during the 2000s he took multiple tours around the country with Mr. Cosby, interviewing Black men and families.

“I think a lot of these males kind of have a father hunger and actually grieve that they don’t have a father,” he told Bob Herbert, a columnist for The Times, in 2007. “And I think later a lot of that turns into anger. ‘Why aren’t you with me? Why don’t you care about me?’”

By then, Dr. Poussaint was addressing a new generation of Black Americans — not the one that had taken lessons from “The Cosby Show” — and some found his message simplistic. He also drew criticism for arguing that racism was partly a mental disorder.

“It’s time for the American Psychiatric Association to designate extreme racism as a mental health problem,” he wrote in The Times in 1999. “Otherwise, racists will continue to fall through the cracks of the mental health system, and we can expect more of them to act out their deadly delusions.”

That position, critics said, risked absolving racists and misdiagnosing the systemic nature of racism in American society.

But Dr. Poussaint continued to find a ready audience among those who understood the balance he was trying to strike between recognizing racism and not allowing it to be an excuse for what he saw as nihilism and irresponsibility.

“I always wonder, whenever I talk to Dr. Poussaint, why he isn’t better known,” Mr. Herbert wrote. “He’s one of the smartest individuals in the country on issues of race, class and justice.”

Alvin Francis Poussaint was born on May 15, 1934, in East Harlem, one of eight children of immigrants from Haiti. His father, Christopher Poussaint, was a printer, and his mother, Harriet (Johnston) Poussaint, ran the home.

Dr. Poussaint described himself as a studious, conscientious child, very much in contrast to his brother, Kenneth, with whom he shared a bedroom. As a teenager, Kenneth suffered from mental health issues and drug addiction and engaged in petty theft to support his habit. He died of meningitis in 1975.

The experience, along with a childhood bout of rheumatic fever, pushed Alvin toward studying medicine. He graduated from Columbia University in 1956 and received his medical degree from Cornell in 1960. He completed his residency at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he also received a master’s degree in pharmacology in 1964.

During his time in Los Angeles in particular, Dr. Poussaint grew convinced that racism was causing a mental health crisis for Black Americans. At the invitation of the civil rights leader Bob Moses, he moved to Jackson, Miss., where he became the Southern field director of the Medical Committee for Human Rights, a group that pushed to desegregate medical facilities and provided health care and training for civil rights workers.

He participated in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march, carrying a briefcase full of medical supplies — more than a doctor normally might, because he knew that few white people along the route would offer to help.

In 1973, Dr. Poussaint married Ann Ashmore in a ceremony officiated by Mr. Jackson. They had one son, Alan, and divorced in 1988. He married Dr. Young, a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, in 1992; together they had a daughter, Alison.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his son, his daughter and his sister, Dolores Nethersole.

Dr. Poussaint joined the faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine in 1967. He moved to Harvard in 1969. He was the founding director of the school’s Office of Recruitment and Multicultural Affairs. He retired in 2019.

Dr. Poussaint’s experience in the South was harrowing. He was repeatedly called “boy” by police officers, who threatened to arrest him when he insisted on “Dr.”

As he told The Boston Globe in 1996, his time working with the civil rights movement made him skeptical of the idea that America could overcome its legacy of ingrained racism.

“When I was involved in the civil rights movement in the South, I believed, like a lot of the people I was working with, that we were going to turn this around in 10 or 20 years; we were going to eliminate racism,” Dr. Poussaint said.

He added, “Afterward, I began to understand how deeply it was embedded in American culture: It was part of the way the country saw itself, the way people behaved and established their own sense of worth, using blacks and some other groups as scapegoats.”