September 17, 2024, 10:00am

There’s a scene in Vinson Cunningham’s debut novel, Great Expectations, when a preternaturally jaded Obama campaign worker is mystified by something he sees on the wall at a donor’s house. Describing the piece as a hodgepodge of text and light, David (our hero) doesn’t initially recognize the neon event for what it is—a piece of modern art. It’s only later, some time farther along in his sentimental education, that he learns the respectable province of the work and its creator.

That creator is Jenny Holzer, a visual artist known for making large-scale, text-based installations. Holzer made her name with the series of “Truisms” posters she mounted around New York in the 1970s. A lauded member of the downtown art world, her work was popularized by adoring critics like Gary Indiana.

Holzer’s work is the subject of a retrospective running at the Guggenheim Museum in New York through the end of this month. “Light Line” is a remounting of a 1989 exhibit, and the project is as awe-inspiring twenty-five years later as it was then. But given the hodgepodge of text and light, this book nerd wondered. How are we supposed to read the work?

*

Holzer is hardly the first visual artist to work with text. Her peers include the anonymous Guerilla Girls collective, the boldly feminist Barbara Kruger, and a mess of folks emerging from a commercial art background, like Ed Ruscha. An even wider canon of painters play with text alongside vivid imagery, like Basquiat.

But where her other text-curious peers went for spare pronouncements, narrative, or absurdity, a lot of Holzer’s work is tonally expansive. As Jed Perl put it in The New York Review of Books, the Guggenheim show resists easy categorization. The centerpiece, a long ribbon of LED-mounted text encircling the famous spiral, “combines pseudophilosophy, wise-guy polemic, and aimless chatter in one gigantic post-Duchampian attention grabber.”

A visitor can stand at the base of the Gugg-stairs and receive instructions like “Destroy superabundance.” But these mandates are framed by more confessional asides, like “I want to tell you what I know in case it is of use.” If you are a text-lover generally out of depth in the visual world, this onslaught of modes and messages can be muddling.

Who is speaking? I often wondered, to the long ribbon of text. Is it the artist herself? Not always. Plaques reveal that Holzer’s work is a blend of personal and found text. Yet it’s not quite anonymous, this voice. Is it my conscience? My inner critic? A pundit, perhaps?

Once I’d admitted these pesky critical questions, I couldn’t resist the urge to hunt for narrative meaning in the exhibit.

Is it a bird, is it a plane, is it…a poem?

*

Better critical minds have debated the whole mode thing in Holzer’s work. I’ll offer that what I discovered when you meet her text like it’s poetry—which is to say, if you read it—the voice can become very clear.

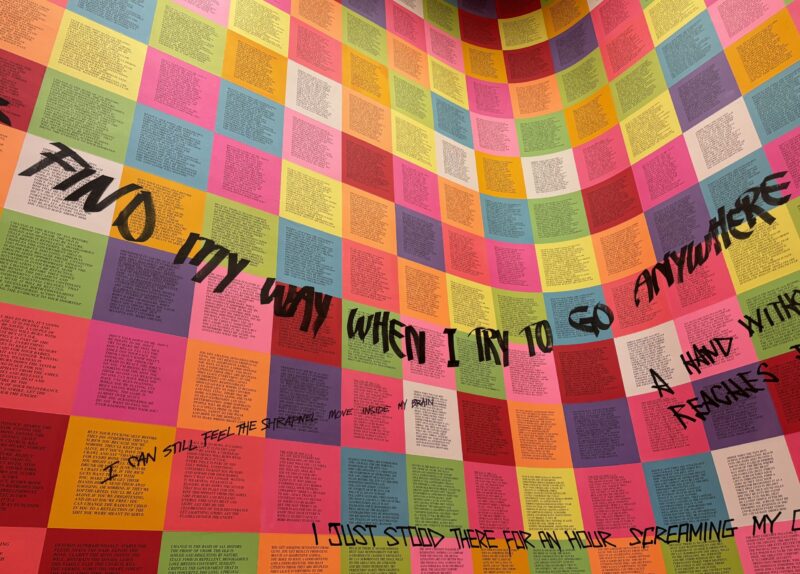

In an antechamber on the first floor, multi-colored pamphlets describe scenes of wartime horror. (Though “Description of Inflammatory Wall: 1979-82” is time-stamped, you can’t help but hear Palestine in text like “The city is in ruins,” and “I can still feel the shrapnel move inside my brain.”)

The bright color scheme does something to lift the text out of a solemn newsroom spirit. But there’s nothing irreverent about any of this reportage. And where an editorial voice is present, so is anger.

One panel indicts an obvious, specific, musky sort of villain. “Here’s a message to you. Space travel is uncertain and any refuge of yours can be blown off the map.”

On the spiral’s upper reaches, you can find similarly unambiguous political messages. There’s a series of Donald Trump’s more inflammatory tweets cast in bronze. And at the peak, a blown-up document details torture methods favored by the U.S. government. These messages made me nod, made me sigh. They did not surprise. But then I wondered if they ever meant to.

In Cunningham’s novel, the presence of the Holzer piece in a chi-chi politico’s home signifies elite capture. For Holzer can be read as the victim of a familiar art world narrative herself. An agitator is beloved, “discovered” by the market, and then pressed into symbolic service bestowing exactly the kind of hollow cache that the early work was designed to protest. As David doesn’t observe in Great Expectations, the fact that Holzer’s art can be repurposed as message art for well-meaning, well-heeled liberals feels a little on-the-nose. But if one digestible truism is all the artist is going for, what then is the point of all this abundance?

In other words. If one clear, activating, right-headed message is the point—why take so many words to say it?

*

There are books that pummel you with text till the words are beside the point. The old one-sentence doorstops. Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport. László Krasznahorkai’s new novel, Herscht 07769. As I wound my way back down the spiral steps, I tried to think of Holzer’s work in that spirit. I let the light run over me like the hodgepodge of text it is.

Released from the trouble of parsing meaning, you can surf the “Light Line” and catch a word or phrase where you will. I enjoyed reading it backwards and forwards. I’d dip in and out, delighting in repetition. I’d grab a musing—”I love my mind when it is f*cking the cracks of events”—and set it down.

When you don’t try to make sense of the messages, the absurdism sings. Some of my favorite text in “Light Line” reads like deadpan jokes. You can imagine a voice-to-voice macro reading it tonelessly aloud. “A lack of charisma can be fatal.” Sure thing. True thing.

And what does all that absurdity amount to? Nothing less than the feeling of being alive today. Noise next to brilliance. The sense that you’re missing something important, as it whizzes over your head.