When Arthur Huff Fauset acquired his 800-page FBI file, he remarked in an unpublished 1981 retrospective of his life: “One good thing about this is: all of my speeches, which I had lost, all of my public utterances, exist now, because the FBI did ‘watch’ over me. It was beautifully done; they get ‘A’ for their work!” Turning the archive of surveillance on its head, Huff Fauset, a Black radical involved in the National Negro Congress, the Philadelphia branch of the Federation of Teachers, the United People’s Action Committee, and possibly the Communist Party, reframed the act of intended destruction as an act of preservation; the FBI’s recording of his life undermined its own goals by essentially archiving his speeches, which would have otherwise been lost to history and even the author’s own memory. In these words written at the end of his life, there is a poignancy to his sarcasm: He may leave a legacy after all, but only through the institutions that silenced him in the first place.

Huff Fauset’s sense of humor about the FBI’s extensive file on him belies the serious consequences of the state’s interreference in and active repression of his life and works as a mid-century Black radical. Born in 1899 in Flemington, New Jersey, Huff Fauset spent the majority of his life working, teaching, and organizing in Philadelphia. After attending the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy, he became a teacher and later a school principal. During his tenure as principal, he would receive his BA in 1921, MA in 1924, and PhD in anthropology in 1942, all from the University of Pennsylvania. He published his dissertation, one of only two monographs he would publish in his lifetime, scholarly or otherwise, in 1944. If Huff Fauset is known to anyone, it is for this, Black Gods of the Metropolis: Negro Religious Cults of the Urban North, which reshaped the study of Black religious cultures by attending to Black religious diversity outside of Christianity, as well as using oral history.

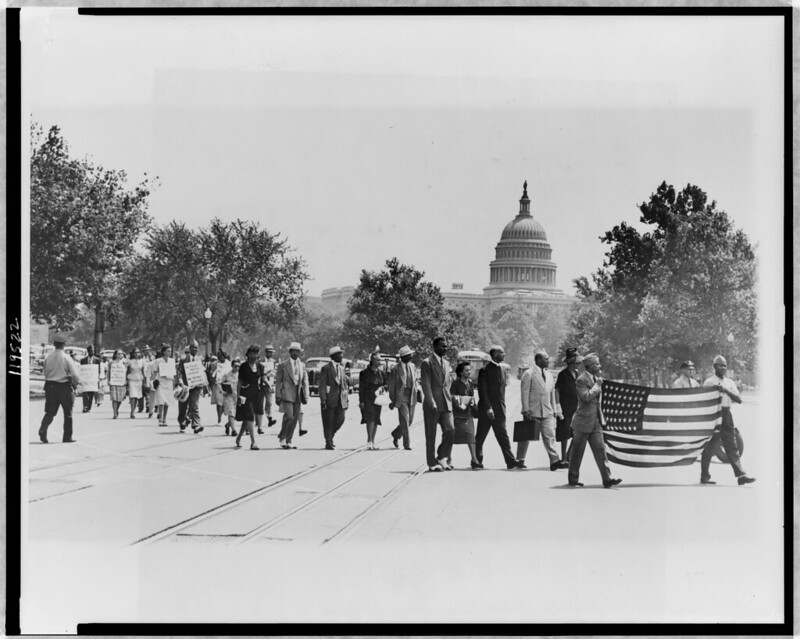

But Huff Fauset also moved in the radical political circles of the 1930s and 1940s that grew in response to European fascism, the Great Depression, and Jim Crow. By the early 1940s, he was known as a prominent organizer in the National Negro Congress, serving as the president of the Philadelphia chapter and its national vice president. His autobiography, which he sometimes also referred to as an “autobiographical novel,” contains a lengthy section about his alias, Rudy McCloy, joining and navigating racial dynamics in the Communist Party. State surveillance followed swiftly after and would continue until his death in 1983. His sudden dismissal from army officer school in Grinnell, Iowa, on the eve of his graduation marks the first recorded incident of the FBI’s attempted destruction of Huff Fauset’s career due to his radical involvements. He later suggested that the National Negro Congress, which he described as a “very important but little remembered or known movement toward freedom in the 1930s,” similarly had been “early aborted, thanks in great part to the alphabetical organizations of opposition such as CIA, FBI, etc.”

In 1946, Huff Fauset was forced out of the Philadelphia public school system due to accusations of being a communist, and moved to New York City. From this point on, less is known about his political life, though he did attend Columbia University’s Teachers College and worked as a public schoolteacher. In his March 3, 1961, correspondence with Langston Hughes, he laments his current employment situation, as he “Got chucked from the NY school system for the same old you know what: (after the Khrushchev incident).” “The same old you know what” is characteristic of Huff Fauset’s rhetoric of plausible deniability—suggesting but never fully articulating his political involvements. More than 15 years later, in a 1977 interview with David Levering Lewis for his book When Harlem Was in Vogue, Huff Fauset joked nervously about an FBI agent calling him the day before the interview, offering his file in exchange for $87. He even recalled, during the height of the House Un-American Activities Committee, an FBI agent visiting his home.

At seemingly every juncture, Huff Fauset’s life was punctuated by increasingly powerful state intelligence agencies hell-bent on stamping out an insurgent mid-century Black radicalism, and particularly Black communists. As author Winnie Williams would later write in a retrospective, he was “buffeted by the excesses of a powerful Agency whose abuses of that power have caused him to be kept under surveillance for many years of what should been a profoundly significant life, and by increasing problems possibly aggravated by evidence of that silent but relentless pursuit.” She concludes by lamenting that “he surely deserved far better treatment from his country than has been shown him.”

At a time when the Left is both resurgent and under attack, looking back to figures who navigated repression, who seemed to be silenced but actually persisted in creating art, even if under the radar, might beat back the tide of nihilism.

Huff Fauset’s elision from literary history, in other words, was not merely a scholarly oversight but a reality constructed in advance by powerful forces. Indeed, his words typify the paradox that Jean-Christophe Cloutier describes in Shadow Archives: The Lifecycles of African American Literature: “That future presence is born out of past absence, that anything saved serves only to remind us of all that was lost—forms the archivescape of African American literature.” On Cloutier’s account, literary archives form a dialectic of presence and absence; the preservation—or discovery—of documents always suggests some prior moment of effacement or repression, while the very act of repression ironically memorializes what is being repressed for future generations. Mary Helen Washington names the series of African American radicals who suffered this state repression and surveillance “the Other Blacklist,” those writers and activists of the Black Popular Front who, to differing degrees, interacted with the Communist Party. This list most famously includes Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and Lorraine Hansberry. Huff Fauset’s memory, however, seems to have been more successfully submerged.

On June 20, 1958, Huff Fauset wrote to W. E. B. Du Bois from Seattle, Washington, describing his simultaneous creative productivity and publishing failures. “Since I saw you last,” he writes, “four years ago at your lovely home, I completed a novel based on Shaka (no-go however), another out here (which will be no-go until we have our own presses, since the Negro is in love with the white girl!) and am now hard at work on another, which while not as significant as either of the other two, I am hoping may see the light of print.” Du Bois responded with a similar lamentation, stating, “There is in the United States a determined effort to suppress all literature by Negroes which does not amuse or appease the Whites, and especially the Southern Whites … Naturally, the ordinary American is not going to pay to read articles or books which are either critical of his group or at least not of prime interest.”

Neither writer suggests that the government had any involvement in their publishing difficulties, but the publishing industry was nevertheless especially harsh to Black writers who moved against the political mainstream. We now know, as much scholarship and reporting of the last decade has shown, that J. Edgar Hoover instructed the FBI to investigate Black writers and even independent Black bookstores. Though Hoover’s infamous Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) was formed in 1956, the FBI’s tracking of African American literature extends all the way back to Claude McKay’s 1922 poetry collection Harlem Shadows, often considered to be the inaugural text of the Harlem Renaissance.

As Huff Fauset alluded to in his retrospective, archives open up the possibility to read around the official political and literary history that government repression has constructed. His literary archive boasts an idiosyncratic collection of stories: a murder mystery within the Communist Party, a conspiracy narrative about a Russian cult, and a fictionalized retelling of the life of Shaka, the 19th-century ruler of the Zulu Kingdom. Murder in the NAJCP, drafted in successive stages between 1958 and 1973, most explicitly engages the vexed history of Black radicalism, American communism, and state repression. This manuscript is a work of historical fiction looking back from 1938 at the moment of Black and communist organizing in the 1930s. The novel follows Thoreau Stokes, an orphan raised in the Black church in Philadelphia, who has become known as a bit of a rebel. After becoming involved in the fictional National Association for Justice for Colored People (possibly based on the NAACP), he is recruited into an organizing project with the Communist Party. Composed of Stokes; a Jewish communist, Max Edelstein; an old-guard Russian Bolshevik, Herman Wolf; and the WASP Joyce Brown, the project’s goal is to make the NAJCP the communist vanguard within Philadelphia’s Black community. The conflict between Stokes and Edelstein forms the dramatic center, as they both desire Joyce Brown, who is eventually and mysteriously murdered. When Stokes is quickly accused of the murder, the party turns on him as well, fearing backlash from the state in an already anticommunist atmosphere. In the end, Joyce’s bigoted grandfather is revealed as the culprit, irate at his granddaughter’s association with Black men.

Murder falls in a tradition of Black literature concerning African Americans’ relationship to communism and state repression, including most notably Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940), Chester Himes’s Lonely Crusade (1947), and Claude McKay’s only recently published Amiable with Big Teeth (1941). Like those three novels, Murder represents the interracial radical milieu of the 1930s. In Native Son, Bigger Thomas is hunted down by the Chicago police after murdering Mary Dalton, the daughter of a wealthy white family for whom he works. Boris A. Max, a communist Jewish lawyer, represents him in court, and in his famous speech explains the socioeconomic conditions that underpinned Bigger’s crime to the jury. Though Bigger is ultimately found guilty and sentenced to death, the novel ends on an ambiguously hopeful note intimating his new, radicalized consciousness. Gordon Lee, Himes’s Black radical protagonist, is wrongly accused of a police murder and hits rock bottom; the communist Abe Rosenberg comes to his aid. At the end of the novel, Lee asserts his commitment to the labor movement despite his experience with corrupt party leadership.

Murder, however, seems to have a distinctly pessimistic outlook toward exploring, as Washington writes, the “[t]ensions between blacks and the Left [that] were exacerbated in the late 1950s as the Left suffered major setbacks under the Red Scare and McCarthyism and as many black intellectuals and activists were increasingly drawn to the black freedom movement.” Huff Fauset began drafting the novel in the wake of Nikita Khruschev’s infamous “secret speech,” addressed to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on February 26, 1956. “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” denounced Josef Stalin as a dictator, especially toward the country’s Jews. After 1956, members left the Communist Party en masse and moved toward struggles in the civil rights, women’s and gay liberation, and American Indian Movement. Khruschev’s revelations exacerbated already existing disillusionment within the party’s Black membership. Considering themselves “America’s Jews,” African American communists had looked to the Soviet Union as an antiracist global force, particularly in its promise to abolish Czarist antisemitism.

The novel does not explicitly engage the “Khruschev incident,” but rather explores an earlier moment when conspiracy theories circulated that the NNC was actually a party front group. Huff Fauset goes one step further to depict the Communist Party conspiring with the state against Stokes. The novel was never finished, so discerning a clear political outlook—to the extent that is ever fully possible with any work of art—is particularly fraught. Rather than presenting a singular and coherent viewpoint, the narrative dramatizes the various perspectives and fears that existed on the Left in the 1930s and persisted into the 1950s, juxtaposing and sometimes mocking them.

The protagonist, Thoreau Stokes, embodies the warranted paranoia about infiltration into Black organizations. Unlike Bigger, Stokes is already radicalized by Murder’s opening scene and is hoping the Communist Party will be his political home. Edelstein assumes a position of authority over race issues, explaining to Stokes “self-determination in the Black Belt” and the theories of Du Bois. Stokes is turned off by Edelstein’s arrogance to the point of conflating his Jewishness with communism itself: “Isn’t this all [communism] a Jewish plot, just like Hitler says? This girl, a plant if ever there was one … Lord help me against such a beautiful limbs … I’m human … human! … must Edelstein parade his superiority just because he’s white! Oh, if only America treated Negroes justly, I would not be here playing this crazy role!” (24). Stokes displaces his anxiety about unseen forces operating in the background of political causes onto Edelstein as a Jewish man and Brown as a white woman. The notions of a Jewish conspiracy for world domination and white women’s inherently threatening sexuality combine to make sense of the oppressive white world. Stokes’s seeming concession to uncomfortably antisemitic ideas is ultimately proven somewhat true when Edelstein testifies against him in court. This is not to say that Huff Fauset was personally an antisemite. Rather, the fracturing Black-Jewish alliance becomes a frame through which to explore Black paranoia.

There is no way of knowing what befell this novel—whether the FBI suppressed its publication, Huff Fauset thought it safer to abandon the manuscript, or he simply moved on to another project that captured his interest more. Indeed, as William J. Maxwell argues in F. B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature, the FBI’s influence on the content and publication of that literature is often difficult to discern because “Afro-modernist literature ‘pre-responded’ to FBI inspection, internalizing the likelihood of Bureau ghostreading and publicizing its implications with growing bluntness and embellishment over the years from 1919 to 1972 and beyond.” Was Huff Fauset’s abandonment of Murder a case of “pre-responding” to government surveillance? The archive does not tell us.

Saidiya Hartman writes in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval that “every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor.” In other words, recovering writers who have been lost to history is no simple task lacking in moral ambiguity, especially for those who experienced persecution. Recovering archives is neither inherently liberatory nor sufficient for political transformation.

Yet, at a time when the Left is both resurgent and under attack, looking back to figures who navigated repression, who seemed to be silenced but actually persisted in creating art, even if under the radar, might beat back the tide of nihilism. ![]()