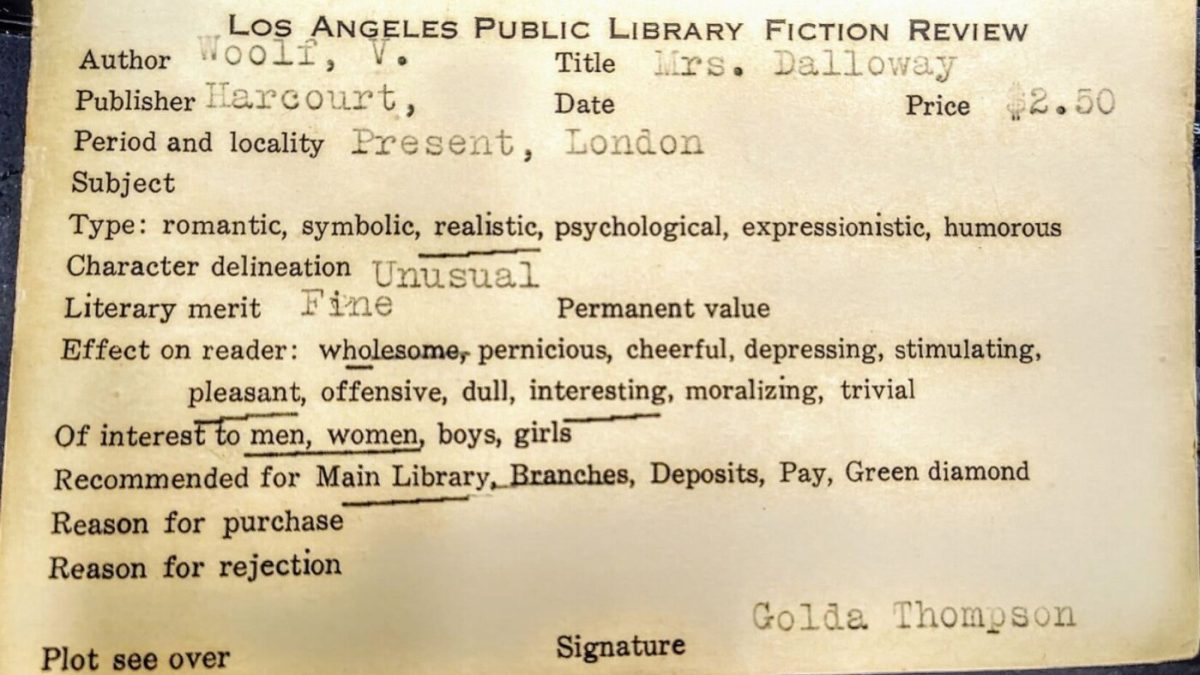

A review card of Virginia Woolf’s 1925 novel Mrs. Dalloway, written by a Los Angeles Public Library staff member around the time of the book’s publication.

James Sherman/Los Angeles Public Library

hide caption

toggle caption

James Sherman/Los Angeles Public Library

Before the internet made book reviews widely accessible, where would curious minds go to find information about a new novel’s subject matter or a plot?

If you lived in the Los Angeles area, you could reference the Los Angeles Public Library’s index of fiction book review cards. The reviews, a collection of thousands of index cards, contain library staff members’ thoughts and opinions about new fiction releases that the library carried. The library system was used starting in the 1920s and into the 1980s.

Robert Anderson, who has worked as a librarian at the Los Angeles Public Library since 1980, says the staff review cards were a handy tool that library staff used to answer specific questions the public had about different books.

“In the the pre-internet days, when you couldn’t just Google something, if people called and said, ‘I’ve heard about this book and I just want to know what it’s about,’ you could pull out the card and read it to them or show it to them if they were in person,” Anderson said.

The reviews, along with being a helpful public tool, also helped staff pick which books the LAPL would order for their shelves. “They didn’t always write reviews for every book, but it was a major way they made the decision on what to buy, particularly for newer authors,” Anderson said. If a staff member reviewed a book favorably, they were more likely to carry the title and order multiple copies, he said.

In a recent video posted to the library’s social accounts, Anderson describes the review cards and walks viewers through their archive. Although the cards are readily available to the public, housed in large drawers near the Central Library reference desk, Anderson said that the video, which was posted on Friday, will introduce most people to the collection.

“They’re in these drawers, but they’re not drawers that have a big label saying, ‘read these 100-year-old staff reviews,’ ” he said.

Anderson said the library still has its entire collection of staff reviews — both books rejected and accepted by the library — from between the 1950s and 1980s. But he said the rejections from before the 1950s were discarded just before he started working at the library. “I think if I had been here, I would have found a box or something to put them in and held on to them,” he said.

The bygone review process was simple: On an index card, library staff would handwrite or type up a short synopsis of a book they read and give their personal review of it. The staff member would then indicate: whether they thought the library should carry the book, how many copies of the book the library should procure, and other details, such as an evaluation of the text’s “literary merit.” The cards offered adjectives that the reviewer could underline to indicate how the story might affect readers emotionally.

For example, for the library’s review of Virginia Woolf’s 1925 book Mrs. Dalloway, the reviewer underlined “wholesome,” “pleasant,” and “interesting.” Of the staff member’s characterization of the book, Anderson said he wasn’t sure why the writer considered Woolf’s writing — which deals with loneliness and other, often dark human experiences — to be wholesome, “but they did.”

Other libraries may keep similar review collections, said Anderson — though he wasn’t aware of any — but he noted that library space is often an issue for housing extensive physical indexes. The San Francisco Public Library, another large library system in California, for example, does not keep an archive of this kind, according to Andrea Grimes, the program manager for book arts and special collections at SFPL. But, she noted, it has saved other old card catalogs made by SFPL librarians.

The Los Angeles Public Library’s index of staff review cards isn’t used regularly anymore, Anderson said. But he said the system now serves as a historical record of both the books, some almost 100 years old, as well as the cultural views held by the book-loving library staff of the time.

“ They’ve become an interesting reflection on not just the books themselves, but on the library staff who wrote these reviews and the attitudes prevalent in the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, on particular subjects,” Anderson said. “Just in the short little pieces of writing on these cards, you can find a lot about the particular time when these reviews were written and about the people who are writing the reviews.”