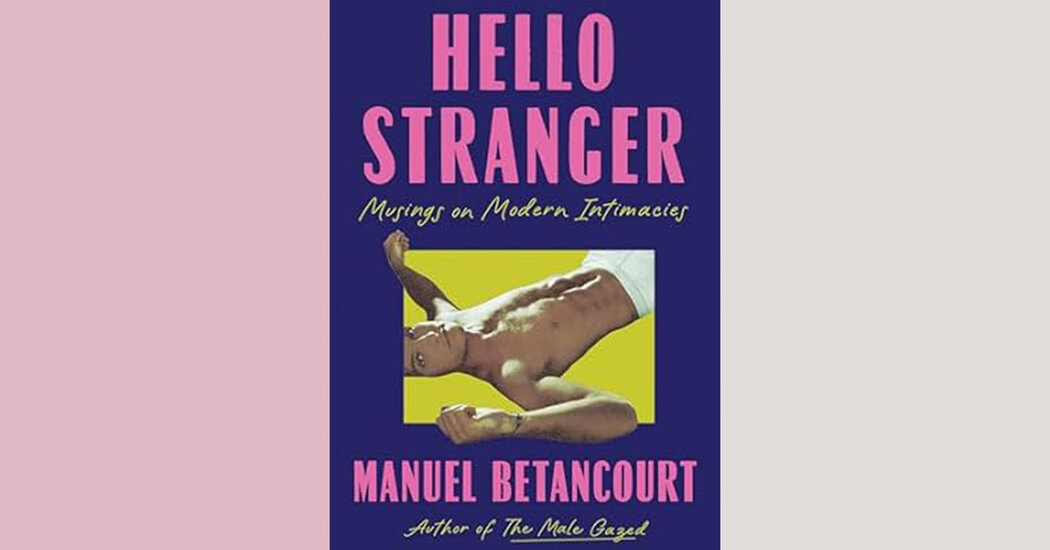

HELLO STRANGER: Musings on Modern Intimacies, by Manuel Betancourt

About halfway through his new book, “Hello Stranger,” Manuel Betancourt recounts his experience in a college course reading John Rechy’s 1977 manifesto “The Sexual Outlaw.” A titillating and raw “documentary” of sexuality in the sleazy underbelly of Los Angeles, the book set the tone for the kind of radically indignant literature that arose from centuries of homosexual oppression and, later, the AIDS crisis. Of Rechy’s insatiable appetite for sex, the young Betancourt had put forth an admittedly glib interpretation. Perhaps, he suggested to his professor, Rechy was simply nursing a fear of intimacy, his impressive body count a testament to his inaptitude for emotional attachment. But Betancourt’s classmates found his take prudish and unsophisticated. “The thundering laughter that greeted my all-too-earnest inquiry haunts me to this day,” Betancourt writes.

To understand casual sex as anathema to genuine, human connection is to reinforce a rather provincial notion of intimacy, the kind typically extolled by rom-coms. But warmth and good feeling, Betancourt comes to discover, can flourish just as easily in bathhouses or under the piers, on iPhone screens or in the affectionate gaze of a nude portraitist.

This realization provides something of a road map for “Hello Stranger,” a collection of essays and criticism about “modern intimacies” — setting up the overwhelmingly wide aperture through which Betancourt examines “the exhilarating thrills of strangers.” And while gay readers will be well acquainted with those exhilarations, Betancourt looks to mount a more sweeping argument against the tyrannies of normative sexuality, insisting throughout that friendship and flirtation might be as spiritually affirmative as monogamy.

To do so, Betancourt brings in case studies from film, literature and queer media, or media that might otherwise be parsed for signs of queerness. Mike Nichols’s 2004 film “Closer,” for instance, illustrates “how familiarity can breed a contentment that doesn’t will away masks but calcifies them instead.” Surveying Alan Hollinghurst’s novel “The Swimming-Pool Library,” the author insists on cruising as an “equalizing” or even “utopian” practice, contingent on a mostly unspoken pact between strangers. The work of the Pakistani American painter Salman Toor, in which the bodies and belongings of gay men are rendered in beatific mounds of paraphernalia, suggests “playful ideas of company and companionship.”