THE LAST MANAGER: How Earl Weaver Tricked, Tormented, and Reinvented Baseball, by John W. Miller

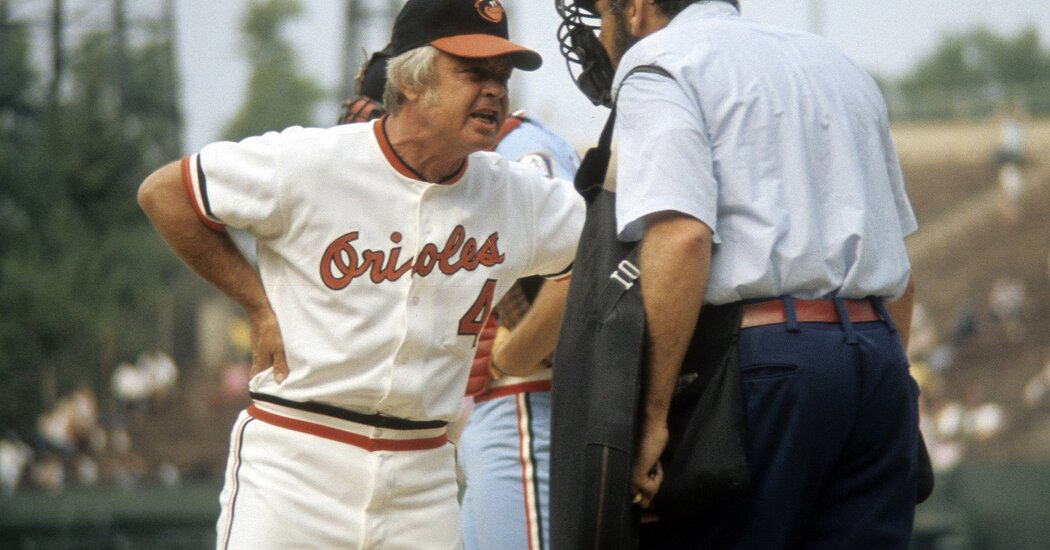

The greatest sight in Major League Baseball during the 1970s was almost certainly this one: the Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver storming out of the dugout to remonstrate over some perceived injustice to his players. He would be so incensed at the officiating — or he pretended to be — that it was if he’d been eating chilies and was excreting flames.

If you were holding a hot dog, this was dinner and a show. Weaver was short and a bit tubby; he resembled Archie Bunker’s better looking, harder-drinking younger brother. He would kick dirt on a base, or yank it out of the ground, or lie down on it, or sit on it like a Buddha. Like Redd Foxx, he faked heart attacks. He performatively tore up rule books. He mimed throwing umpires out of the game. Officials got so upset when Weaver “beaked” them in the chest with the bill of his cap that he was forced to flip it around when arguing. He was ejected repeatedly, and fans ate it up. In Baltimore’s old Memorial Stadium, one sportswriter commented, he was like Elvis playing Vegas.

Weaver, who died in 2013, is the subject of a vivid new biography, “The Last Manager,” by the writer and former Orioles scout John W. Miller. Most sports books are pop flies to the infield. Miller’s is a screaming triple into the left field corner. He takes Weaver seriously; he understands why his tenure mattered to baseball; he is alert to the details of the unruly pageant that was his life; he explains, a bit ruefully, why he was probably the last of his kind, an unkempt dinosaur who ruled before the data geckos came into power.

Weaver’s antics wouldn’t matter if weren’t a superlative manager. He led the Orioles for 17 seasons, from 1968 to 1982 plus an ill-advised return in 1985-86. During this time the Orioles had five 100-win seasons, and won six American League East titles and four pennants, including three in a row from 1969 to 1971. The team took the World Series in 1970. They were a treat to watch, and rarely out of contention, in the other years.

It’s one of Miller’s central arguments that Weaver’s instincts as a manager made him a walking precursor to the stathead era. He prized throwing strikes, getting on base and playing impervious defense. He matched players to situations. “Once computers came along, you didn’t even need a manager anymore,” Miller writes. “You could just program them to think like Earl Weaver.”

Free agency, as well as computer analysis, has sapped the power of managers. If a slugger doesn’t cotton to his manager these days, he goes elsewhere. Miller takes us back to the time when baseball managers were almost mythical characters, cornfield philosophers who were “plucked from the America of train travel, circuses and vaudeville, springing from the 19th-century clubs in New York and other cities that turned an informal folk game into modern baseball, America’s first mass entertainment.”

This biography is good from the start because Weaver’s story is. He grew up with baseball. He was born in 1930 in St. Louis, where his father had a dry-cleaning business that took care of the uniforms for the Cardinals and the football Browns before they moved to Cleveland. Young Earl had a backstage pass, of a sort. He also had a mobbed-up uncle who taught him to gamble sagaciously. The gambler’s eye is the stathead’s eye. Earl honed his analytical skills.

He didn’t attend college. Weaver played minor league ball for too many years. He was famous for his hustle. He was a scrapper who would fight guys twice his size. He never made the big leagues, but he came devastatingly, traumatically close. Klonopin did not exist then, but beer did. Weaver drifted into coaching.

Miller doesn’t try to clean Weaver up. “You would not have wanted him to date your daughter,” he writes. He was a bit seedy. He harbored “streaks of pain and anger he could never master.” He gambled on everything except, apparently, baseball, and he smoked three packs of Raleighs a day. (He had a special pocket sewn in his uniform to hide these.) He swore like a man who had dropped an anvil on his toe.

Weaver drank, almost nightly, until he was half-comatose. After his second D.U.I., he commented: “If you’re a teetotaler, I guess this looks pretty bad.” For baseball, he thought he was doing OK. Bill James, baseball’s philosopher-analyst, once estimated that 18 of the 25 greatest mangers were alcoholics.

It’s a tribute to “The Last Manager” that the tangents are good. There’s one about a fastidious man known as the Sodfather, who cared for the grass at Memorial Stadium. Weaver was pals with him from the minor leagues. The Sodfather tailored his mowing job for each game — maybe letting the grass stay a little long, for example, to keep down bunts.

Weaver was a flawed man, but Miller’s book is largely a paean to his ebullience. He had deep reserves of underdog charm. He loved his players, and, with a few exceptions, they loved him back. He loved Baltimore, and he remains a folk hero there.

Baseball managers today, in interviews, dispense clichés until you want to double Van Gogh yourself. Weaver liked to hold court after games while nude, drinking beer, smoking and eating fried chicken; sometimes he’d keep talking while at the urinal. He’d say things like, “We’ve crawled out of more coffins than Bela Lugosi.”

Miller catalogs a lot of Weaver’s best lines. He liked to comically hassle players he considered overly religious, for example. When one told him to walk with the Lord, he replied: “I’d rather you walk with the bases loaded.” When the same player hit a home run and commented that the Lord had been watching out for him, Weaver replied: “We better not be counting on God. I ain’t got no stats on God.”

The publisher Robert Giroux once said that publishing should be done by failed writers, people who “recognize the real thing when they see it.” Maybe something similar is true about scouting and coaching. It certainly was in Weaver’s case.

Robot umpires are being tested in spring training this year. I’d kill to see Earl kick dirt into their sprockets. He was a major national asset. He wanted his epitaph to read: “The sorest loser who ever lived.”

THE LAST MANAGER: How Earl Weaver Tricked, Tormented, and Reinvented Baseball | By John W. Miller | Avid Reader Press | 331 pp. | $30