Firmly in the mess of her mid-twenties, Vi is fresh off a breakup, pretending to submit Peace Corps applications, and working at the front desk of a hotel in a midwestern college town. Outside of a dive bar one night, Vi finds a blob. She thinks about the slime she used to make as a kid, the kind made from Elmer’s glue and shaving cream, among other things. But, this blob breathes. Or, if breathing is too strong a word, at least at first, the blob’s body moves up and down. It’s alive. And it has beady eyes that seem sort of sad.

Lonely and wanting, Vi brings the blob home to her basement apartment. There, limb by limb, the blob becomes a man, aptly named Bob. Raised on a steady diet of Lucky Charms and television, his looks inspired by a collage of heartthrobs curated by Vi herself, Bob is a hot, blank canvas onto which Vi can project her greatest desire: to be loved.

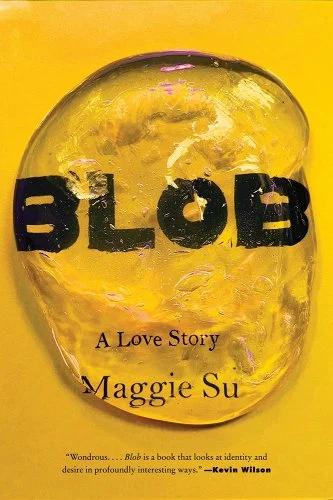

With humor and honesty, in her debut novel Blob, Maggie Su crafts an absurd, compelling creation story that raises questions about love, belonging, identity, and what truly makes us human. Is a perfectly curated partner a dream or a nightmare? How does what we consume impact how we become who we are? How can relationships influence the stories we tell about ourselves? Can we ever really know anyone else?

I talked to Maggie Su about creation myths, efforts at control, relationships, and critiquing elements of culture that have caused harm.

Jacqueline Alnes: Can you just talk to me about Blob/Bob? I love him and want to know where he came from.

Maggie Su: I’ve always been really interested in speculative conceits and playing around with “what if” scenarios. At the time, I was really interested in relationships and how people connect. I found it so alien and strange and unlikely that you would meet someone. For some reason, it just blew my mind. I wanted to take the idea of romantic connection and make it into something as unlikely as I feel like it is to find a partner.

This started as a short story and turned into a five-minute play. By the time I started writing the novel for my dissertation, it was during COVID and I was stuck in my basement apartment (much like Vi) and I was feeling the isolation and loneliness. That’s where Blob and Bob came from –– moments of desperation and staying inside.

JA: I won’t spoil anything, but reading about Bob felt like a kind of creation story. Like a lot of creation myths, once the entity has agency, they can make their own decisions and the initial perfect premise is ruined, or changed. In love, you want someone to love you and stay with you, but you can’t force it; it’s such a devastating reality.

MS: It’s like the beginning of so many relationships, where you project your fantasies onto someone. The desire to control how things turn out. That’s one of Vi’s fatal flaws, is that she not only wants to control Bob, but also believes this myth that you can fully know someone. In her past relationship, she wants to know exactly what her ex-boyfriend is thinking. Every time he keeps something to himself, she wonders what it means. Blob allows her the opportunity to know everything about him because she created him. He is mine. I can keep him here. I think her realization that sometimes these things are outside of your control, you have to allow for space and allow people to be who they are, you can’t know everything about someone, are frightening and scary for her. I had fun playing with that balance through the speculative element.

JA: What Bob knows of the world comes from television and eating cereal. We see Bob watching something like Top Chef or wrestling and that becomes his language. It made me think about what we all consume on a daily basis, especially when we are in isolation. When we’re lonely and screens are what we turn to, our perception of the world can become so warped. Could you speak a little more to what Bob being new to the world allowed you to access?

MS: I loved being able to play with pop culture. The editors have these lists of my proper nouns and it became almost a found poem: Pop-Tarts, Fruity Pebbles, Top Chef, Padma Lakshmi. All these wonderful proper nouns pervade the book.

That’s how he’s learning about the world and that’s how we all learn about the world. I have a flashback where Vi is watching The Swan, that plastic surgery show that was on where they go in as “ugly ducklings” and come out after getting plastic surgery. I watched that as a kid, in my parents’ basement. There is critique there of the culture we grow up in and what we see represented. I think Vi not seeing herself represented anywhere and the microaggressions that exist in this small, midwestern town all came together to form her. I wanted race to be a part of the book, but I didn’t want it to be something that describes why she is the way she is; I wanted it to be a factor out of many. She is already an odd, difficult person, and you add this in and she’s wondering how her otherness fits within this society.

For Bob, I wanted to play with the newness, how he can see Jeopardy! or watch wrestling or consume porn. There was something exciting to me about having a character who doesn’t have as many hang-ups as Vi and seeing that creation –– and the difficulty he goes through about who he is and his identity crisis. Vi has that realization that everyone, even Bob, goes through this feeling of not knowing where they fit.

JA: And the way you do that with Rachel, too. She is this bubbly, blond coworker at the hotel and I think Vi has a perception that Rachel has it all together. But, the way she romanticizes her life means she never actually sees Rachel, in some ways.

MS: She feels like there are all these narratives that other people have and are able to follow and that for some reason, she’s not. She’s envious of people that are able to follow the scripts society has given them, or subvert them, or go between them more easily than she is.

JA: I longed for Vi to be able to accept love and also to finally love herself. Living as a Taiwanese-American in a midwestern college town and grappling with this quarter-life crisis on top of everything else –– things are rough for her at different points in the book. My question is, what did writing her allow you to explore?

MS: I was inspired by messy female characters. Some people will hate her and I won’t actually get offended by that, because I’m like, well, you hated her but you read the book, so something must have interested you about her. That’s all I can hope for. I rewatched that Season 2 Fleabag episode, the dinner episode, I think it’s fantastic. One thing I was learning from reading and thinking about flawed characters –– I mean, all characters are flawed! –– but I wanted there to be a mixture of lightness and darkness. I think the reason we are able to watch Fleabag is because there is that mix of comedy there as well.

I wanted to write a character who represented a messy Asian-American woman. I think we are seeing that more and more with Asian-American stories; it’s not just the Marie Kondo neat, perfect Asian-American daughter. There are bodily messy, socially messy, flawed women. The ways these stories connect to larger stories about race and go against the singular immigration narrative that has been really prevalent in Asian-American literature.

She’s a tricky character and I hope whether readers love her or hate her or find the horrible things she does forgivable or not, that they can see a character who is searching for love in the wrong places. It was important for me to have those vignettes of her backstory not necessarily to show why she does the things she does but instead: What are the forces that make us feel unlovable or unworthy or ungrateful? What is the guilt that we carry from place to place? There are certain things in our past, maybe, that we focus on where we made a mistake or didn’t do the right thing and Vi holds those closer to herself than anything else. She has this script for self-hatred and she’s having to unlearn that. It’s corny, but the love story is very much a self-love journey.

JA: Some of this relates to something you said earlier in our conversation about representation. Every person that Vi collages into Bob was in a magazine as like the “hottest hunk you should date.” I think the traits of what we see in movies or magazines or the qualities that were romanticized are narratives that don’t serve us. In the end, those are never real people.

MS: Definitely. It’s ironic because Bob is new and he is somehow still more socially adept than she is. He is able to find a connection with these frat boys and Vi is like, what? How are you able to do this?

JA: Parts of the story feel so absurd and hilarious, which helps lighten the darker moments or bring relief to Vi doing something that feels inexplicable. This book seemed fun to write. What did humor allow for?

MS: I remember complaining to my thesis advisor and she was like, you just wrote a scene where a man pops out of a pool like it’s a porno. How are you struggling? And I was like, that’s true.

It was a fun conceit. Bob added a lot of lightness to the book and optimism, in certain ways. His newness helped Vi get out of this stuck feeling she was feeling –– and he felt like that to me, too. When COVID was happening, there were a lot of dark news stories and a lot of isolation. To be able to escape into my writing and escape into these absurd situations brought me a lot of joy. I don’t ever write with the intention of being humorous, so I’m always a little surprised when it happens, but I like contradictions, I like putting things that are dissimilar together and seeing what happens.

The absurdity of working at a hotel, I had that summer job working the front desk at a hotel and sometimes when you are in that really mundane setting, you can find a lot of little humorous moments.

JA: I worked at a bed and breakfast and what struck me about working there –– and what you capture so well in Blob –– is just that humans are so weird. When they are walking through the lobby, making requests at the front desks, having interactions or fights that you get snippets of, it’s all so wild.

MS: I think when people are in hotels, they forget! They’ll come down in pajamas, more power to them, but you see glimpses into families, volleyball tournaments, dynamics. It was a fascinating ecosystem.

JA: For you, working through isolation especially, what was in the front of your mind to work through while writing this book? What questions were you interested in answering?

MS: I am in a very different place now. While writing, I was in isolation, in my twenties. I think it was me trying to digest the messiness of the dating scene, connection and relationships, intense loneliness, and really reflecting on what it meant to me to grow up in the midwest. Obviously Vi is not me, but so many of those experiences of feeling that otherness were. The pandemic and sitting with myself and sitting with my own thoughts and sitting alone really allowed me to channel it into something I could deal with. I started going to therapy for the first time, so I think that helped. A lot of people during the pandemic had to really come to a crisis point where they looked at their own lives and partially this book was that. And my thesis advisor was saying, your first book has been living in you for a really long time and it’s the one you need to get out. I felt that way about this book. I’m excited to move on.

JA: Reading this made me think about how hard it can be to see ourselves in that way where it’s raw and honest. It’s difficult to want to fully perceive yourself. It seems that Bob almost becomes this mirror for Vi, where when he enters her apartment she suddenly realizes the state of her apartment, she thinks about what she wears, she starts buying food. She starts being perceived in a way she has tried to ignore for the past few years of her life. Relationships, even if they are not right for you, can encourage self-reflection.

MS: So much of the book is how these external forces shape our characters. Vi is waiting for an external force to shape her, in some ways. She thought that her ex-boyfriend was this lifeline where, okay, I can just hold onto this person who seems normal and that will be my lifeline into this scripted, normal life that I’ve watched on TV. That will save me from loneliness. With Bob, it’s something she can control. In that way, I gave her what she thought she wanted. She thinks she can figure out how to be a person in the world through Bob. But I think you’re right. I think he provides a lens for her to want better for herself, in some ways, because she has to take care of him and therefore take care of herself.

JA: What did you learn from writing this book?

MS: I wrote a few novels for NaNoWriMo, but I would just abandon drafts so easily after that. The process taught me to trust myself and to follow what felt good in terms of writing. It’s very Yoga With Adriene. It’s been a dream of mine since I was a kid to publish a book, but it taught me a lot about trusting the process and trusting the reader. I wondered if it would be too much for people, is this unforgivable character going to pull people in or push people away, but it’s been really wonderful to learn that people have connected to some of her, regardless of whether you’d get a beer with her or not.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.