Several months ago I was lucky enough to meet a Riverhead publicist at a mixer for Black folks who work in book publishing. We started chatting, and she mentioned that she was working on Danzy Senna’s soon to be released novel, Colored Television. I felt, in that moment, like a chasm in the earth had opened underneath me. I have long been a huge fan of Senna’s work. I first discovered her writing in the fall of my freshman year in high school. I was a new student at a wealthy, conservative, and very white all boys college preparatory school on a majestic, rustic campus in Hunting Valley, OH. Having transitioned from public school, I was having some trouble adjusting to the environment, and rather than socialize during my free periods, I roamed the stacks of the library. The school may not have been for me, but the library was exquisite, like something out of an east coast boarding school fever dream. Every day I explored, pulling books down from the shelves. I felt subversive, judging each book by its cover and jacket copy, and choosing whether or not I was going to read it. That year, I discovered Arundhati Roy, Anna Quindlen, and Norman Mailer, among others. I also discovered Danzy Senna, and her luminous debut, Caucasia. For the first time, I was aware, as I read, of that feeling you get when you are truly seen, understood in an authentic way, because you see your experience reflected on the page for the first time.

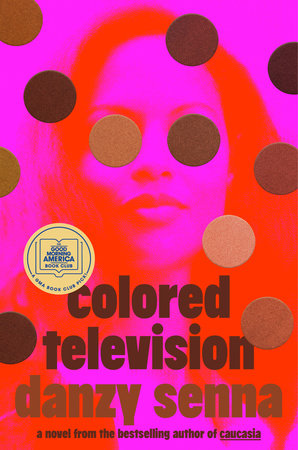

Here was an author who wrote about what it meant to live at the intersection of multiracial identity, to feel equally pulled in multiple directions, some of which were at odds with your surroundings. I was smitten, and have remained so in the years since. Colored Television, published in September, is clever, laugh-out-loud funny, and unafraid to bask in the complexities of multiracial identity. I had a wide-ranging conversation with Danzy Senna about making art, selling out, and the evolution of our priorities as we age.

Denne Michele Norris: I love beginnings, so I always like to ask writers about the genesis of their work. I’m wondering where this novel came from? What inspired it?

Danzy Senna: It was many years ago that the inklings came to me. I’ve been living in L.A. for many years as a novelist, and I kept wanting to write about L.A., and I love the literature of L.A., and I kept thinking ‘Where’s my L.A. novel?’ But the first inklings of this novel were a family, this Black family that occupied a fluid place in the creative class. So often novels about Black families are steeped in tropes where they’re either living in poverty or they’re super wealthy, moving on up to the east side, and I was interested in this other class space of Blackness, this creative class where there’s a lot of wealth of culture, but the bank account is low. And I also wanted to write about a Black couple where it’s a more equal relationship, but there are problems nonetheless, and then I started dipping my toe into Hollywood, and I was like wait a minute, this stuff is really good. These people were giving me some really good material.

DMN: Just to go back to the class stuff for a minute, one of the most interesting things about this book, you’re right, is that it subverts the tropes around Black storytelling related to class. You’ve got the creative class, the intellectual class, but as you said, this family doesn’t have much money. They’re nomadic, but they’ve had the chance to settle into this mansion and really fantasize about a different life. And Jane gets completely swept up in the fantasy.

Our dreams and identities and fantasies are so, so susceptible.

DS: I see her as a really susceptible person, and I think you see that in the origins of their relationship: the psychic telling her whom she should be with, and her getting fixated on an image and a catalog. I’m fascinated by how much we’re influenced by the images that are fed to us. Our dreams and identities and fantasies are so, so susceptible. And Jane, in particular, is even more vulnerable to how people see her, how she is read, so much so that her identity becomes wrapped up in these images and fantasies, and how she thinks the people around her are seeing her. And she’s always been this way.

DMN: Let’s talk about Jane as a character. She is delicious. Her obsession with status is amazing, her snap judgments about everyone around her are unwaveringly accurate. Her belief in the novel she’s writing, which as a reader, I knew was doomed. I found myself feeling so many things for her, and about her—loving her, judging her—and I’m wondering what it was like to write her.

DS: All of my characters are shadow selves of me. I’m exploring aspects of my own self, and the people around me, but I’m cutting out other parts of myself to zoom in on some element, some flicker I saw in myself. By the time I’m finished writing, it’s no longer me, it’s this other figure that might be a cousin to me. I have all the same feelings: love them, don’t trust them, find them infuriating, but also delicious. So she articulates things that might flit through my head, and I let her go down that road even further. But it’s like the id. She brings out all these qualities that we suppress in ourselves. Her obsession with status, for instance. I was tapping into the parts of me that have that. Her susceptibility to popular culture and to aspirational fantasies. We all have that, and mostly we repress it, but for the character I take it, perhaps, 10 degrees further. But she’s not wrong all the time. I don’t distance myself from her entirely, nor did I with my last character. I like the darkness in my characters. I think you have to love that if you’re writing them.

DMN: It’s funny because my first novel is coming out next spring, and all I do in my free time is scroll trulia and look for homes I could buy in other parts of the country—because New York City is astronomical, right? I never really thought I’d want to leave New York, never thought about buying property, but it’s recently become something I really want. So as I was reading this, I kept thinking about doggedly pursuing your art for so long, for so many years, which is feels like both Jane and Lenny have done, and allowed each other to do, and then sort of reaching a point where you begin to realize that life is more than just the art you want to make.

DS: It becomes about aging, too, and about growing into reality. I lived on coffee, chardonnay, brie, and crackers for years in a row apartment in New York. I’d get up, work until 10, then go to work, and come home and work on my novel. And I remember that self with such affection. But I can’t live like that now. I have children! But it’s also that you get tired and you need more balance and you need vegetables, you know? And this is part of Jane’s susceptibility. She’s moving through the chapters of her life. Thinking of the Jane that lived in Brooklyn, for her it’s like looking at herself through a window. She feels separated from that self, and she’s torn between Lenny, who’s happy to keep being nomadic, and Hamilton, who’s the extreme opposite in that capitalism has completely taken hold of him. And for Jane, it kind of comes down to her kids. They’re her reality check because she’s left thinking about how their lifestyle affects these two little people they must care for.

DMN: I wanted to go back to what you said earlier, about your characters being shadow selves. I read a review, recently, that ende by drawing a connection between you—Danzy, the writer, the author—and Jane. I wanted to ask you about the reader’s tendency to conflate the author and the character, especially when you do write characters that resemble you, or come from your background. Does that impact how you approach writing fiction? How much do you think about it?

DS: I have a lot of thoughts on this because if you are a woman of color, or any marginalized identity, you will be assumed to be writing a diary, or autobiography, much more than if you are a white male writer. Somewhere in there is the idea that you are not capable of the complexity of writing fiction, and if it has any resemblance to you, then surely, it’s confessional. And that’s steeped in racism, sexism, and the condescension that you didn’t write 500 drafts of this and aren’t deeply in control of this as a construct. This was never a diary, though I am aware of all the ways it will be read that way. But the trick, then, is on the reader, because this took so much conniving to write fiction. I am as much Lenny as I am Ruby, as I am Jane. All of these characters were created by me, so all of them come from me, in some way. I think that the more marginalized you are, the more you’re going to be read as only being capable of writing autobiography or memoir. With my first novel, that happened to me hundreds of times when I was going out and talking about that book, and in the reviews. And it’s one of the things I’m most proud of about Caucasia—that it was complete bullshit. Everything in that book was constructed. I never went on the run with my mother. I never passed as white a single day in my life. And so that book is the result of deep intellectual thought and creative construction and work, the labor of creating something that is new. And that I think this is stolen from you when that assumption is made.

DMN: That’s such a great answer to a very complex question

Unless the reader is in my body, they don’t know how much fictionalizing I did.

DS: It can look as much like you, have as many autobiographical details as you want, and it can still be completely fictional. Unless the reader is in my body, they don’t know how much fictionalizing I did. And in order for me to write a book like Caucasia or Colored Television, I had to create some fictive distance. You must create that between yourself and your main character, even if it looks like you, even if the biographical details are yours. And I just really think that labor is stolen from writers who are assumed to be writing about themselves.

DMN: I’ve never heard anyone address that assumption in that way, and I think it’s hugely important because you’re right, it’s labor that gets stolen from writers of color, queer and trans writers, all the time. I’m going to adopt that language. I remember reading Caucasia, and looking at your author photo, and then wondering how much of that novel was autobiographical, back when I first read it in high school. And then I thought to myself, this couldn’t possibly be autobiographical! I thought to myself, so Danzy Senna was on the lamb with her mother, spent her teen years living on a hippie lesbian commune? I realized it was an absurd assumption to make, right then and there.

DS: You had enough common sense to know that! So much of that novel was in dialogue with Faulker, with Black literature of the 20th century, and that’s other labor that’s taken from you. That I’ve read literature and I’ve thought about these things in a bigger, more abstract way. But also, and let me think how to put this. When I went out and tried to sell Caucasia as a young twenty-six year old debut writer, all of these editors I met with wanted to know if this was true, if this had ever happened to me. And I when I said no, that none of this ever happened to me, that I found in my life a point of departure, that I’d thought about my life with my siblings and my Mom and my Dad, and thought how could I find a place to digress from the truth, and go into the construct, this one editor said good, that means you’re going to write other novels. If this was true, this would be your one, thinly disguised novel and we’ll never hear from you again, but if you can make this up, you can make up many stories. And I think when people ask you to piece together what part is true, and what part is made up, they’re asking you to do something impossible with a novel. Jeanette Winterson said a line that always stuck with me. She said asking someone to do that is like asking someone to turn wine back into grapes. The process is done. This is the wine, and the grapes are in there.

DMN: My feeling is that Colored Television is gesturing at something profound about the commodification of Blackness in the world of art making. I’m thinking about Lenny, and about how early the book Jane feels like adding one small “emblem of Blackness” would make his art sell out at shows, but he refuses because it feels commercial. Then by the end of the book, Lenny is painting more racialized work, and it’s selling out, and they’re able to engage in some of that class mobility Jane has been working towards for so long. So in the end, Jane gets some of what she wants. And I am curious what you think about that.

DS: I had this rather strange interview a few weeks ago where the interviewer, a white guy, was disappointed in Lenny for choosing to racialize his work, for having capitulated in the end, and putting this little emblem of Blackness into his work. And I sort of reject that notion, that somehow making one’s art more overtly racial lessens it, or goes against its purity. Like, maybe it makes the work better. After Caucasia did so well, a lot of gatekeepers in publishing suddenly and overtly suggested that I move on from the race thing and graduate, and become one of the white girl writers. It was like, “Okay, you get to be a real artist now because you can put the origin story to bed. You get to write real novels that are more universal in scope.” And I firmly reject this. That is a weakness of white literature, it’s inability to write about race. From a purely artistic perspective, that is a strength of being a Black writer. To see America as an outsider sees it makes you more capable of seeing the bigger picture than if you’re too steeped in the blindness of whiteness. So I leave it to the reader to decide whether or not Lenny made his work better or worse, but I certainly don’t think it means that his work is less pure, or less artistic, or less valuable.

DMN: How do you think Lenny feels about it?

DS: I don’t know. I leave it to the reader to decide what they think. But that’s kind of what I’m grappling with in this novel, at the beginning anyway. Because the questions of Black representation that we face would, I think, shock a lot of white writers who are never asked to think about these things. Like, can I write about this, or from which angle should I write about this? Our awareness of the white gaze is there from the moment we set pen to paper, and part of our work is to find all of these strategies that allow us to be free of that, to write what we want to write, in the way we want to write it. And so, through Lenny, I was looking at someone who makes the choice to obscure and reject that pressure to commodify his Blackness in his art, and then through Jane, someone who embraces signaling their Blackness in their art. But they’re both facing the same pair of eyes that they must navigate throughout the novel.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.