In rare archival footage, James Baldwin strolls down the sidewalk of 71st Street, surrounded by a band of close-knit family members. Baldwin is gleaming with his classic, wide-open, toothy smile as his nephews cling to his fingers.

Article continues after advertisement

The clip cuts to Baldwin beaming as he holds one of his nephews wearing a bright yellow brimless hat. He enters a Manhattan apartment building, a white-brick, four-story rowhouse Baldwin purchased for his family and as a second home for himself. He resided there from 1965 until his death in 1987, commuting between his Manhattan apartment and his villa in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France. He lived on the lower level, his mother was right above his head, and his sister, Gloria, on the fourth floor.

When Jimmy would approach his Manhattan apartment, after being away in France, “Jimmy’s coming” echoed through the four-story building. Raging complaints by nearby neighbors about the ruckus over Jimmy’s arrival broke through the walls. Aisha Karefa-Smart, James Baldwin’s niece, recounts in her essay, The Prodigal Son, “Uncle Jimmy’s being home meant… the word spread like wild-fire; it was as if a village drumbeat, or a trumpet fanfare announced his arrival. Somehow folks just knew: Jimmy was home.”

In Little Man, Little Man, Baldwin chronicled the same themes he tackled in his adult work, blazing the way for adults to explore difficult realities through the clear-eyed view of a child.

As the word of Baldwin’s arrival got out, additional family members, literary luminaries, and “various other artists, and musicians” would come from different pockets of New York to cling to Jimmy.

In the foreword of the reprint of Little Man, Little Man Baldwin’s nephew, Tejan Karefa-Smart describes the apartment as their “wonderland-village,” and details being enraptured by the coming together of all the “artists, musicians, painters, sculptures and real-life poets” in his uncle’s Manhattan apartment.

137 West Seventy-first Street was a gathering place. In this noise-filled apartment with its mixture of gospel music, Motown records, and feverish discourse about racial tension, Tejan always found Baldwin’s hand and asked him constantly, “Uncle Jimmy! Uncle Jimmy, when are you going to write a book about me?” In time, a box arrived from France, containing copies of Little Man, Little Man, Baldwin’s first picture book about his own nephew, Tejan Karefa-Smart and his playful childhood.

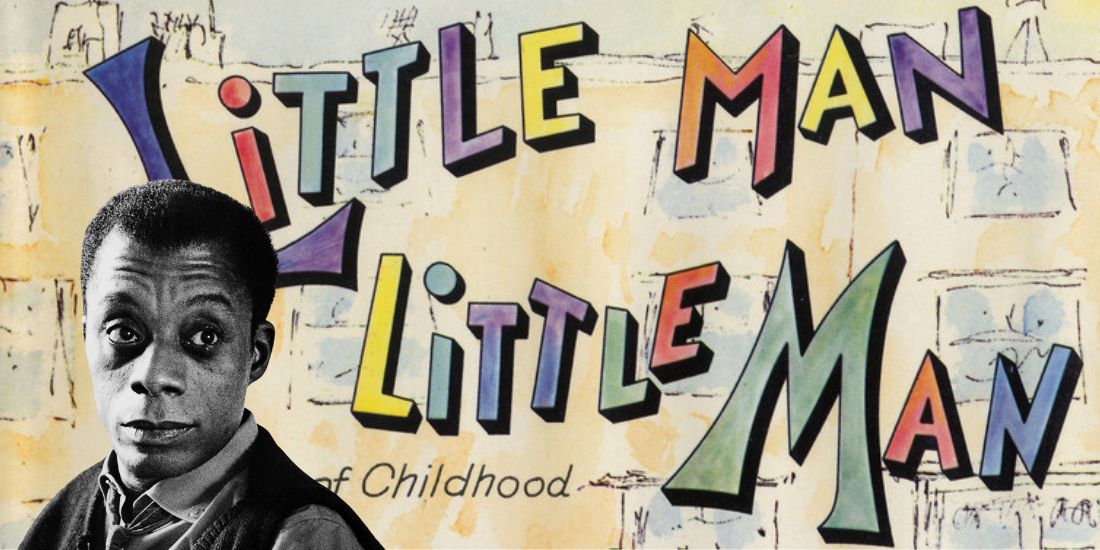

Little Man, Little Man is Baldwin’s only picture book for children. It was published in 1976 by Dial Press with art by Yoran Cazac, a Parisian visual artist. Initially drawn with crayons, Cazac rendered the final illustrated text in scratchily sketch lines and vivid watercolor. The story of Little Man, Little Man, a colorful depiction of a Harlem neighborhood, was inspired by Baldwin’s Manhattan apartment, and Tejan himself.

*

As the story’s protagonist, TJ, roams whimsically through Harlem with his basketball and his friends, he is watchful. He sees the day-to-day challenges and allure of his Harlem neighborhood. He’s watching the cops, jump ropes, the drunken neighbor, sprawling streetscapes, the people on the stoops who look like they have nothing to do, the record stores, the corner store, the storefront churches—all of these images denoting the “challenges and joys of black childhood.” In a sense, Little Man, Little Man follows the sensory awareness of a child primarily through sight, depicting a typical day in Harlem.

Little Man, Little Man deviated from the conventions and traditions of children’s literature. At that time most African-American children’s books highlighted merely positive images, obscuring mature subjects. In Little Man, Little Man, Baldwin chronicled the same themes he tackled in his adult work, blazing the way for adults to explore difficult realities through the clear-eyed view of a child. “Children are not easily fooled,” Baldwin said at the Library of Congress in 1986.

As a former second-grade teacher in an all-black school in Cleveland, Ohio, I know firsthand that if you spend enough time around a child, you’ll notice that their eyes are always searching beneath the surface. And like TJ, they look unflinchingly into the world around them.

When you consider the complicated content of Little Man, Little Man, you can see the ways in which it inspired other children’s books that underscore issues of racial injustice and prejudice. For example, Choosing Brave by Angela Joy, tells the story of Mamie Till-Mobley, Emmett Till’s mother and Unspeakable by Carol Boston recounts the the Tulsa Race Massacre. Both of these texts squarely take on difficult historical accounts for children, marking them as part of the brazen legacy of Little Man, Little Man.

James Baldwin’s letters always find a way to echo again, even when the world is too afraid to face American History through his blistering, beautiful voice.

Little Man, Little Man was not commercially praised, and it did not garner extensive appeal like most of Baldwin’s critically-acclaimed books. In response to how the story seems to meander as TJ and his friends run errands, an acclaimed children’s book writer, Julius Lester, wrote a review in the New York Times children’s book section, stating that “there are brilliant flashes of the Baldwin many of us love…but the book lacks intensity and focus.” For me, this so-called lack of focus gorgeously allows for black children to be boundless and free on the page and celebrates their whimsiness in the face of searing realities, which further underscores all the ways in Baldwin’s words, “American history is more larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

Though Little Man, Little Man went silently and swiftly out of print, Baldwin adored the book for what it fulfilled for Tejan. It succeeded in “celebrating the self-esteem” of his nephew—who, after all, got to see himself in print for the first time, surrounded by his neighbors and his friends. That was most important to Baldwin.

Little Man, Little Man resurfaced after being out of print for 40 years. It was republished in 2018 through Duke University after scholar Nicholas Boggs located an original edition at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. It took him a decade to get it published again. But James Baldwin’s letters always find a way to echo again, even when the world is too afraid to face American History through his blistering, beautiful voice.

During the early drafting of Go Tell It: How James Baldwin Became a Writer, I sensed that I needed a jolt of inspiration. Something in addition to secondary sources such as Baldwin’s gorgeous mix of letters, his essays, plays, novels and James Baldwin, a biography by David Leeming. I wanted to be acquainted with something other than sheer text to lead me through crafting a lyrical biography about my literary hero for young readers.

In 2021, on a whim of impulse, I drove from Cleveland to New York and through the throng of traffic. I drove up and down 71st Street, searching for parking. I found a gap between a yellow taxi and a van. I parked and arrived in front of 137 West 71st Street, a Manhattan apartment, which attests to Baldwin’s love for family. This white-brick apartment, I imagine, is where Little Man, Little Man began.

__________________________________

Go Tell It: How James Baldwin Became a Writer by Quartez Harris, illustrated by Gordon C. James, is available from Little Brown Books for Young Readers, a division of Hachette Book Group.