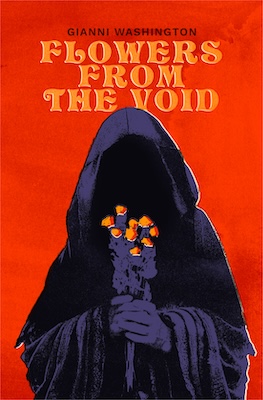

The lights go out. And in the darkness two friends banter—until one sees something. A portal into another realm? The friends are frozen and a figure appears announcing they tell stories here. It doesn’t matter if the friends want no part of this, the monsters’ greed is bottomless. That’s the prelude to Gianni Washington’s debut short story collection, Flowers from the Void (CLASH Books). Published in the U.K. this past spring by Serpent’s Tail, the collection is now available to American readers who enjoy short stories that veer into the strange and haunting.

This prelude acts as a clever framing device for the collection, allowing Washington to showcase a wider range of stories regarding tone, narrators, and voices than might otherwise be expected. Some of the stories stick close to our world, others stray from it. Often the alternate realities aren’t immediately apparent, so the reader is lulled into the world of the story before realizing what trepidation awaits, other times that’s clear right away. Most of the stories are contemporary, though not all—one takes place in the 17th century with an African witch preparing to join a coven of white women. On the surface, the compilation of stories might seem rather hodge-podge, as if they don’t quite fit together aside from a shared creepy factor. But a deeper reading reveals the immense heart bubbling underneath each of the stories. Because while they are indeed unsettling, they’re much more than that; they’re pulsing with empathy and united by how they highlight what we all have in common: a shared humanity. And each story is skillfully written—something that becomes even more apparent the second time around. Washington is an inventive and talented writer, elegant on the line level, emotionally intelligent with her characters, no matter how monstrous, and able to weave unforgettable macabre stories that linger, but also should be pondered. Flowers from the Void is a smart, imaginative collection by a notable new voice in fiction.

I had the pleasure of talking to Gianni Washington about this diverse range of stories, rereading, and the horror genre.

Rachel León: Typically when I interview authors it’s before their books’ pub date, but we’re talking after your collection was published by Serpent’s Tail and before its launch with Clash Books, so I thought we could start there. Can you share what it’s been like to first debut abroad? I’m wondering if that somehow lessens the pressure, or maybe it adds to it?

Gianni Washington: It’s a bit of both. I feel some pressure regarding how the book will be received in the U.S. versus the U.K., especially because the book is still quite new and finding its ideal readers across the pond. A staggered release draws the process out, giving my mind free rein to come up with every awful scenario possible. On the other hand, I appreciate the chance to experience talking about the book in public ahead of its release here because I anticipate (maybe hope is a better word) that it will get easier the more I do it.

RL: I hate to ask, but how would you describe this book’s ideal reader?

GW: Really, I suppose the book’s “ideal” reader is me, haha. The risk of publishing anything is that readers won’t be pulling from the same bank of references as you, the author, and as a result, won’t get as much out of the work as you hope they will. That said, my ideal, non-me reader is receptive, compassionate, observant, and thoughtful; in other words, someone who reads in good faith.

RL: I love that because despite how these stories tend toward strange and otherworldly—horror, if you will—I felt like they’re united by the idea of what makes us human. Which isn’t what I anticipated from the book’s description.

GW: That’s exactly what I hope readers will take away from this book! I really enjoy using the unfamiliar to highlight the familiar. Because we can only know the intricacies of our individual lived experiences, we spend a lot of time feeling misunderstood. But I tend to attribute that misunderstanding more to the different ways we communicate and receive information than an actual inability to relate to one another. Putting characters in strange, sometimes horrific situations is one of my favorite ways to illustrate that we all have access to the same range of emotions, regardless of the circumstances we find ourselves in. Even if you can’t exactly relate to what a character is going through, you can probably relate to how it makes them feel.

RL: Maybe now’s a good time to talk about the range of the collection, which I found impressive: these stories are all so different. I hesitated to say ‘horror’ earlier because while some feel that way, others feel more gothic. There’s an incredible range here, and you pull them all together beautifully with a framing device. Could you speak to the way these stories stretch across the collection?

GW: I wanted to give readers as many opportunities as possible to connect with whatever style, situation, or character resonated with them most, as well as wanting to showcase my own breadth as a writer. The framing device was incredibly useful as a sort of home base for each story, keeping them all united thematically. Though the stories vary, I always seem to return to the same concerns: life as performance, emotional isolation, metaphysics, belief, and fear. I sometimes wonder if I shot myself in the foot by not keeping the collection more cohesive on the surface, but in the end, this is a far more authentic representation of me than I could have asked for. It can be pretty nerve-wracking to expose so many aspects of your inner world publicly, but worth the terror if it means reflecting some part of a reader back to themselves.

RL: Publishing anything that exposes our inner world is terrifying, but it seems almost poetic to do so while writing terrifying stories. Like spreading the fear around!

GW: Agree! Sharing your fears and questions and whatever else is swirling around inside your head is ultimately such a good thing because there will always be someone else out there who feels how you feel or has the same questions. Spreading the fear around can help nullify it because you create new ways to consider that fear, which can lead down some exciting rabbit holes that are more fascinating than they are frightening.

RL: Speaking of fear, I’m curious: are you into scary movies?

Because we can only know the intricacies of our individual lived experiences, we spend a lot of time feeling misunderstood.

GW: There are horror films I really liked that have stuck with me: Hereditary, The Ring (one of the few Hollywood redos I prefer to the original), the old Pet Sematary (1989). My favorite ones are also hilarious. I saw The Cabin in the Woods in the cinema without watching the trailer or knowing anything about it and it was one of the best film experiences I’ve ever had. The original Texas Chainsaw Massacre is bonkers. I also really dug The Menu and Get Out, which was hilarious and scary because of how much of it I recognized. My absolute favorite pieces of screen-based horror media are on TV. Mike Flanagan’s adaptation of The Haunting of Hill House is a masterpiece. The way the story maintains its fright factor while also being a completely engaging character study… I love, love, love it. Another fave, The (original) Twilight Zone, though not always horrific, is always thoughtful and imaginative.

RL: It’s interesting you mention humor because I tend to shy from straight up horror because it often seems one-note. I need something to go along with the dose of fear, and humor is the perfect partner. That’s another thing I enjoyed about your collection: there’s humor here, which I really appreciate.

GW: Humor has a grounding effect—it strengthens the connection between the fantastical stories we read or watch and the reality we live in. If you can see what’s funny in a situation or share a laugh with a character, you’re primed to immerse yourself further into the story as a whole. I mostly included humor in the form of banal observations and thoughts we’ve likely all had at some point as opposed to actual jokes.

RL: My favorite kind! Though, there are also a few jokes in the opening in the form of dialogue. Which brings us back to the framing device. I’m guessing that wasn’t always there. At one point did you bring it in?

GW: The framing device was actually there from the beginning! I love Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man—probably my most memorable encounter with a framing device in short fiction—and I thought it could be fun to try out something similar. Once I knew what stories I definitely wanted to include, I built the framing device around them, then wrote the remaining stories with the established framework in mind.

RL: I badly want to talk about individual stories, but I don’t want to spoil them for readers! That said, as delightful as my first read was with so many stories taking unexpected turns, I think I’m enjoying my second read of the collection even more. I’m dazzled by all your clever craft choices, so I encourage readers to revisit this one. Most avid readers seem to fall into one of two groups: Camp Never Reread and Rereaders like myself. Which are you?

Spreading the fear around can help nullify it because you create new ways to consider that fear.

GW: I am definitely a rereader. Sometimes it’s just to see if a story can still make me react as strongly as it did the first time. But usually it’s to see what I notice that I didn’t before. It’s thrilling to discover additional nuggets of interest in a story I already love. It can make a story feel neverending, in a good way. I do see where Camp Never Reread is coming from though. I get a little sad when I think about the books I won’t get around to.

RL: Yes to seeing more the second time around. One of my favorite stories in the collection is “Under Your Skin,” and knowing what would happen allowed me to notice things I hadn’t in my first read. Plus, rereading helped with one story I’d initially misread the narrator’s identity in—the back cover notes the tales are told through the lenses of Black, female, and queer narrators, so I read the one in “Hold Still” as female the first time, only realizing my mistake five pages in. It was a more enjoyable read without the confusion! Because one of the things I love about your work is its subtlety. It feels like you trust the reader. Is that true?

GW: Oh yes—Black, female, and queer, but different combinations of those characteristics, or only one of the three (or none in one case). I do have faith in the reader! When I read, it excites me to notice small details without everything being spelled out, so I try to give other readers a similar experience without leaving them confused. Striking a balance between being clear enough that the reader will enjoy the story, and staying true to your own style and creative goals is an ongoing challenge.

RL: I loved the range of narrators, especially because the differences echo that idea of what makes us human—we all experience fear. Why was that something you wanted to explore and showcase, like out of a full range of emotions, why fear?

GW: Confronting what scares me has always turned up important information. It happens every single time and I love how that feels. Some of my narrators have fears that I write them through; others only make it to the point of figuring out what frightens or confuses them, but even that helps them to understand themselves better. I think there’s value in facing what terrifies you, and in revisiting who you think you are, especially if you end up changing your mind.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.