“This is so boring!” Luka Dončić moaned.

Article continues after advertisement

The Lido di Roma Tournament featured a day off for each of the age-13-and-under teams competing at the event, an opportunity for some education and to experience Italian culture. The Union Olimpija team packed into a van to make the short trip to Ostia Antica, a massive archaeological site and popular tourist destination at the location of ancient Rome’s harbor city, where remains have been discovered that date back to the fourth century BC.

“Bad idea,” remembered Matteo Picardi, the tournament director and organizer of the field trip. Every five minutes or so, the tall kid with dirty blond hair who was clearly the leader of the Ljubljana, Slovenia, squad approached Picardi to complain.

“Let’s go to a basketball court!” Dončić pleaded.

A lot of players call the court their sanctuary. For Dončić, a phenom with a flair for entertaining, it was a stage.

A basketball court, without question, was where Dončić felt most comfortable. A lot of players call the court their sanctuary. For Dončić, a phenom with a flair for entertaining, it was a stage.

Dončić grew up in Slovenia—a small country in the basketball-mad Balkans that gained its independence from the former Yugoslavia in 1991—as Saša Dončić’s son. His dad was a six-time All-Star in the Adriatic League with a guard’s game, a big frame, and a giant personality, a man with whom everyone in the country wanted to sip some wine or chug a beer, and a great many succeeded. Saša’s playing career spanned almost two decades, and for the last several years, little Luka was essentially part of his teams. He hung out in the locker room before and after games and usually sat under the basket during the action, sweeping the gym floor when called upon. The boy always had a ball within reach, jacking up jump shots or putting on impromptu dribbling exhibitions in time-outs and at halftimes.

When Saša jumped from the Slovenia club Domžale to Union Olimpija, his 8-year-old son went with him, joining the longtime powerhouse’s youth program. He practiced with his age group for a grand total of 16 minutes before the coaches realized that Dončić belonged with much better competition, putting him with the 1996-born group, kids three years older than he was. After one practice with the older group, Dončić was promoted to the Olimpija selection team—a feeder system for the pro club—where he routinely dominated his age group and more than held his own when playing in age groups three or four years older.

The game isn’t just easy for Dončić; it’s natural. “I don’t even think he sees. I think he feels,” said Lojze Šiško, who was the director of Union Olimpija’s youth program. “You can learn to see, but you can’t learn to feel what is on the court. There’s a big difference.”

As much as is possible for a 13-year-old son of a pro, Dončić had carved out his own name in Slovenian basketball circles and beyond before the Italian trip. Months earlier, he’d even received an invitation from Real Madrid, one of Europe’s most prestigious clubs and arguably the world’s best basketball team outside of the NBA, to play for its squad in the Minicopa Endesa, the junior version of a high-profile Spanish tournament. Dončić starred, scoring 20 points in a championship game loss to Barcelona, capping the performance by banking in a half-court shot at the buzzer—a meaningless bucket but quite memorable, nonetheless.

Nobody who witnessed Dončić’s performance on the afternoon of April 9, 2012, will ever forget it. The boy played with a flair in that small Roman gym—where wooden beams crisscross the ceiling and much of the light comes from windows in the dull, sea-green walls behind the baskets—that foreshadowed his future performances in front of packed crowds filling the world’s most famous arenas.

Dončić, wearing his father’s No. 4, put the finishing touches on Union Olimpija’s run to the Lido di Roma Tournament title with a 54-point triple-double in the championship game rout against the Italian club SS Lazio. Dončić scored at will, putting up 39 points by halftime, shooting three-pointers with effortless form, and displaying a polished, innovative off- dribble game—attacking at ease with either hand, freezing defenders by changing directions and speeds, creating space in crowds with pivots and power, finishing with an array of floaters and scoop shots.

With the score lopsided in the second half, Dončić sought the spectacular, passing the ball like a young artist playing with his paints and enjoying the experimental process. No-look feeds, behind-the-back passes, driving full speed, and blindly flipping the ball behind his head to an open teammate. He nutmegged a kid while bringing the ball up the floor, crossing over by dribbling between the helpless Italian boy’s legs.

“In this moment I told someone that he reminded me of a young Dražen Petrović,” longtime Olimpija basketball chief Srečko Bester said, invoking the name of arguably the greatest guard ever to come out of Europe. “He was a killer with a baby face. It was so easy for him.”

Was all that showmanship necessary? Maybe not, but it sure was fun. Dončić has always had an intense competitive drive and a tendency to get bored when he isn’t challenged. It’s why his coaches, from age 8 up to the NBA, orchestrate practice drills to have winners and losers as often as possible. During games, Dončić sometimes challenges himself to see what magic tricks he can pull off, stretching his imagination while testing the limits of his skill set. Over-matched opponents become extras in his theater acts.

There were only an estimated 600 spectators in the crowd that afternoon, but word of Dončić’s sensational performance spread quickly. He wasn’t just one of the best basketball prospects ever seen in Slovenia, a nation of just more than 2 million people that had produced a handful of NBA players. He was an elite talent by European standards, which is why Real Madrid soon offered Dončić a five-year contract to leave home for Spain and train in its renowned youth academy, which would put him on track to eventually play for a perennial EuroLeague contender. Dončić had also already landed on the radar of at least one NBA franchise’s scouting department.

Roberto Carmenati, a scout stationed in his native Italy, called one of his bosses soon after the Lido di Roma Tournament. “Tony, there’s an amazing kid that you must go see!” former Mavs director of player personnel Tony Ronzone recalls Carmenati saying.

“At that age, you hear that all the time,” Ronzone said. “You’re like, right, okay. But he’s just a special kid.”

Whether to accept Real Madrid’s offer was an emotional decision for Dončić. At 13, was he ready to leave the comforts of home in Slovenia for the unfamiliar land and language of Spain? His mom, Mirjam Poterbin, suggested that he could wait a little bit to make such a life-changing commitment. Dončić replied that he wanted to go, deciding that he was willing to sacrifice his adolescence in pursuit of his potential as an international basketball star, prompting mixed reactions in his hometown.

Dončić sought the spectacular, passing the ball like a young artist playing with his paints and enjoying the experimental process.

“Maybe some other staff at Olimpija, the GM, maybe they were angry because he was leaving,” said Šiško, the director of Union Olimpija’s youth program. “But the coaches working with him in the last three years with Olimpija, we knew that it was a great opportunity, and he must leave Ljubljana to become such a big player.”

It was agonizing for Poterbin, a former model and beauty salon owner who had divorced Luka’s father in 2008, raising their son in a Ljubljana apartment that overlooked the outdoor basketball courts where he spent much of his free time. After leaving Luka at Ciudad Real Madrid, the club’s expansive campus about fourteen miles north of the city, Poterbin bawled on the flight back to Slovenia. The cultural transition was tough on Dončić, too, who lived in a small dorm room with roommates from Spain and Bosnia, attending school around a demanding basketball schedule. He had to rely on hand gestures to communicate with his first Real Madrid coaches as he learned to speak Spanish.

The basketball transition, however, wasn’t hard at all. As he had done in Slovenia, Dončić dominated while playing against older boys, drawing comparisons to Ricky Rubio and Nikola Mirotić, prospects recruited by Spanish clubs in their early teens who blossomed into EuroLeague stars before becoming first-round NBA draft picks. Months after Dončić had moved to Madrid, the Spanish newspaper ABC proclaimed that he had emerged as the best basketball prospect in all of Europe.

Another clear sign that Dončić was destined for the NBA: he signed with BDA Sports, the agency run by Bill Duffy, one of the league’s most powerful agents. Duffy’s client list is headlined by Hall of Famers Yao Ming and Steve Nash and includes a pair of prominent Slovenians: Rasho Nesterović, Dončić’s godfather, who played 12 years in the NBA; and Goran Dragić, Saša’s former teammate who was starring for the Phoenix Suns at the time.

“When we recruited him when he was 13 years old, we already knew we had something special in our hands, which was going to be very different from other players we’d had before in Spain,” said Quique Villalobos, a former Real Madrid player who was BDA’s representative in Spain. “We weren’t 100 percent sure, but we had the feeling we had some kind of gold in our hands.”

Dončić collected MVP awards while leading Real Madrid’s teams to championships at top junior tournaments throughout Europe’s elite club circuit. Real Madrid’s established pros followed Dončić’s exploits in the same manner in which Americans keep up with a generational college prospect projected for NBA stardom, such as Zion Williamson during his lone season at Duke. “When he played guys his age, he was killing them! We always checked his numbers,” said Salah Mejri, a center on that Real Madrid squad. Dončić started practicing with Real Madrid’s top team at age 15 and even appeared in a preseason game.

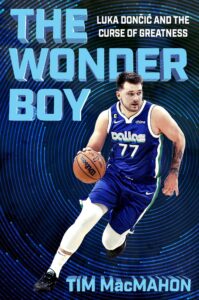

By then, the Spanish sports newspaper Marca had dubbed him “El Niño Maravilla.” Translation: The Wonder Boy.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Wonder Boy: Luka Dončić and the Curse of Greatness by Tim MacMahon. Copyright © 2025 by Tim MacMahon. Published by Grand Central Publishing, a Hachette Book Group company. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.