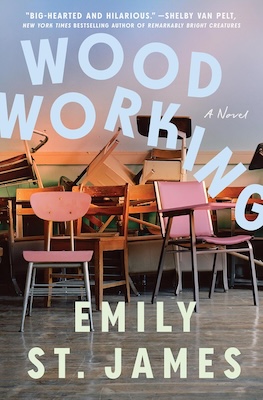

Emily St. James’s debut novel Woodworking chronicles the developing friendship between a 16-year-old trans girl and her recently-out-to-herself English teacher in Mitchell, South Dakota in the months leading up to the 2016 election. In a town like Mitchell, secrets are few and far between, making Abigail’s transness and Erica’s recent divorce fodder for gossip and inquiry. When Erica comes out to Abigail, it sets into motion a ripple effect that will travel through their community, bringing to the forefront a network of women that support and challenge one another, ultimately forcing each of them to look within themselves and make room in the world for what they find. With undeniable wit and a wealth of empathy, St. James tells a story about not only finding oneself, but what comes next.

The going-ons in a rural American town leading up to Donald Trump’s first election serve as a welcome reminder that not only is the personal, in fact, political, but also that the trans experience is universal despite the American political machine’s growing insistence that it’s an error of psychiatry. These two women of vastly different experiences who have exactly one thing in common forge an alliance both necessary and inconvenient. Inadvertently, they ask a town to reckon with what is expected and accepted, catching some unlikely figures in a clandestine web of connections. Woodworking—a term used describe the practice of post-transition re-closeting to live a life of assumed cisgenderism—becomes a looking glass through which anyone’s true self can be concealed or revealed, simultaneously highlighting life’s greatest possibilities and unearthing our deepest fears about ourselves and the society in which we live.

Christ: There is a parallel between the circumstances in Woodworking and the experience of publishing your first book with the background of Trump taking office.

Emily St. James: A lot of novels are now set in 2016 because it’s weirdly a fertile ground for dramatic irony, but I wanted to capture the way that support of trans people has backslid. I picked a bathroom bill because those were popular in 2016 and South Dakota’s governor at the time, Dennis Dugard, had vetoed a bathroom bill. Reality dovetailed with the book’s world. Now there’s all this legislation, especially aimed at trans kids and it’s horrifying. I anticipate every interview I do about this book is going to be like, Well, what do you think of the current legal landscape for trans people? It stinks. It’s bad. It’s not good. As a trans woman, I am aware that everything I write is going to be read through that lens and be perceived as a political statement from people who interpret my existence as political, but I was not interested in writing either the Aaron Sorkin version of the trans lady standing up and making herself known or the leftist small group of trans women band together and survive against all odds through mutual aid and fighting the state. I would gladly read those books, but I was interested in these specific characters and their relationships. It’s weird to have started writing this book about Trump coming to power when it seemed like he was out of power and then publishing it at a time when he’s coming into power again. It’s a very history-repeating moment.

C: The political touchstone of bathroom bills was perfect because they rely on passing, which is inherent to the concept of woodworking.

A lot of novels are now set in 2016 because it’s weirdly a fertile ground for dramatic irony, but I wanted to capture the way that support of trans people has backslid.

ESJ: Bathroom bills, as you said, are effectively a question of passing. Abigail points this out and she doesn’t have to worry about this because she started hormones when she was 16. How she presents herself is recognizable in a way we define acceptable as society. She’s an outsider, punk, whatever you want to call that style. If she gets a look askance it’s because she’s constantly dyeing her hair wild colors and it’s not to do with her transness. The circumstance of why she is constantly read as trans and wants to disappear is entirely because of where she lives.

I know a number of trans kids growing up as themselves. It’s not clear to me why when they reach adulthood, they should have to say, “by the way, I’m trans.” There is this idea in our brains that trans solidarity necessarily requires no anonymity. At the farmer’s market, I’m not Emily St James. I’m just some lady. That anonymity is precious. You cannot be yourself 24/7. You have to have time to just be another person. The weight of constantly being out is so wearing. Erica is going to have to go through that. I don’t like passing discourse because it’s placing a value judgment on your genetics and you can’t control that. It’s a space in which the various trans characters in the book have different relationships.

C: Given the contextual nature of anonymity, do you view woodworking as a spectrum?

ESJ: I realized later in writing the book that every character is woodworking to some extent. Erica, by not being out, is woodworking as a cis man. Constance is constantly trying to turn herself into the person she thinks her boyfriend wants. Woodworking, to some extent, is just about blending in with society in a way that doesn’t scare or offend people around you. Trans people make this overt in a way that threatens and scares some people, but we’re all going through it. Woodworking is setting aside questions about yourself, your environment, and society to be able to more effectively hide within it. I don’t want to totally talk down the idea that sometimes we have to go along to get along as a social bonding mechanism, but I do think it’s worth constantly asking ourselves, “What am I doing here that doesn’t actually bring me meaning and joy in my life? And is there a good reason to be doing that?” All of these characters are navigating a society within which they feel oppressed in different ways and grappling with what that means for them.

C: A lot of woodworking happens without that self-interrogation, so many people will just go along to get along without even making a conscious decision.

ESJ: I grew up in the world of this book, where it was like “This is who you are and this is who you need to be.” The second you start placing rigid boundaries around people, they’re going to find ways to break out of them. Queerness says if we accept that the boundaries aren’t real, then we can let people define themselves and then figure out new boundaries.

C: How does the book’s varied use of perspective among the three central women speak to their individual experiences of embodiment?

ESJ: One character talks about transition as not just going from a person perceived as male to a person perceived as a woman, but to herself and having that moment of suddenly seeing through her own eyes. That’s just going from third to first person. Erica has been vastly dissociated from herself for her entire life, and the process of the book necessarily had to be about her ceasing to do that. You’re seeing someone rise to the surface from the bottom of the ocean, but very deliberately so they don’t get the bends. There is a level of the third person voice that’s dissociative that lends itself to Erica.

First person is very blinkered. Lots of things are left out. Famously, most unreliable narrators are first person. I knew Abigail had to be an unreliable narrator in some way. Abigail has to have something about herself she’s not looking at. She didn’t live with her parents and they ignored her and she had a lot of pain around that. Then, of course, I immediately started thinking, “Well, what’s second person?” And then I got to some fun places.

C: The book is about the informal networks of support women build. What factors were considered as you mapped out the various networks in these characters’ lives?

ESJ: A support group felt necessary. I needed a space for Abigail to talk and for Erica to feel like “I can do this”. The support group was important to me in early transition. A seed for this book was a woman in my support group who transitioned in the ’80s and went deep stealth and never told anyone she was trans. It was the third or fourth meeting I’d been to and I was scared to present femme. She had a breakdown. She said, “I need community.” Some part of me realized we were in the same boat, even though we had drastically different experiences.

There is this idea in our brains that trans solidarity necessarily requires no anonymity. Anonymity is precious. The weight of constantly being out is so wearing.

Friendship with other women was so important to me when I came out, with other trans women, but also with cis women. It’s very powerful to have a friend who just sees you as who you are. It’s easier to find that in a trans face, but you will find cis people who are that way. I certainly have. I wanted to write about friendship and what it means to build a political movement in a space that is actively pushing against you doing that.

Erica’s noticing other people. She doesn’t realize it because she’s thinking about them looking at her, but I tried to capture a solidarity among people that’s not necessarily political. There’s the solidarity of just being in a restroom with someone and them giving you a little nod. We have established a human contract here. These connections feel so fragile and easily disrupted by the world, by politics, by people who want to destroy them, but they’re the strongest thing alive.

C: Throughout the novel, there’s a sense of inherent, sometimes even subconscious recognition between trans women that sometimes extends to their network of cis friends. Where does this come from and how does it function in a rural town like Mitchell?

ESJ: When you live in a rural area, you have to have the world’s best queer-dar. There is the experience that trans women often talk of, of seeing someone who is an egg and knowing them for who they are. There’s a disconnect behind the eyes that we recognize. The book is about recognition and that spreads in different directions. Again, this is something transness makes overt that we all go through. There’s power in seeing someone for who they really are, accepting them, and then trying to reincorporate that vision of them into your life. We are all very bad at it and need to get better at it. Trans people are loved every day. Trans people are held tightly by people in their lives every day. And I wanted to show that something like that could happen in South Dakota as easily as it could happen here in Los Angeles.

C: The narrative possibilities in Woodworking expand because you’re not at any point slowing down to make explanations or try to change anyone’s mind.

ESJ: That made it possible for me to do a story where transition is the setting in a weird way. It permeates everything, it’s everywhere and also nowhere. I wanted to write about the parts of transition that you don’t see.

There’s the space between when you self-accept and when you begin medical transition or begin presenting in a way different. You have plausible deniability, where you can kind of re-closet yourself. You can live in that space for the rest of your life where you know you’re trans and aren’t going to do anything about it. That’s fine and you can do that, but I had never seen a book that explored that period. The drama here was not the beats of the transition story. The drama here was, “Before I can do this, I have to work on myself.”

About a year into hormones, every trans person realizes that there’s other stuff in their brain. It’s like you’re in a house and there’s carpet everywhere. The process of taking HRT often means pulling up the carpet and now you can see the floor, but you see all the saggy spots. Those are not because of your gender. Maybe you struggle with depression, maybe you have trauma. And now you can see those because you don’t have this muffling layer over them. Abigail’s story is so much about that.

C: How is Erica and Abigail’s friendship complicated by ideas of motherhood?

Woodworking is setting aside questions about yourself, your environment, and society to be able to more effectively hide within it.

ESJ: Every major female character in the book is really trying to be Abigail’s mom. Erica gets the closest to being that mother figure largely because she’s not trying and because she sees Abigail as her mom in a very specific, limited set of circumstances. Motherhood is having someone that you want the best for, that you are protecting constantly. Especially once they’re 16, 17 and know their way around the world, you’re just there to be a home base for them. If you think of motherhood as being a home base then, in many ways, Erica, and Abigail serve as mothers to each other. We think about motherhood within this very concrete set of circumstances, but sometimes it’s about having somebody who tells you how to put on finger nail polish.

C: Abigail and Brooke both connect to being an “American Girl” through music. How do their respective songs speak to their unique experiences of girlhood?

ESJ: I’ve always seen “American Girl” by Tom Petty and “Your Best American Girl” by Mitski in conversation with each other. The Tom Petty song is about this woman being seen from the outside in an admiring way, but fundamentally, this guy doesn’t know her. Mitski has said very explicitly the song is about the experience of growing up a woman of color in the United States where the ideal white blonde teenager is Taylor Swift. That song also has value to a lot of trans women I know because it’s about throwing yourself against the wall of a country that doesn’t want you. It’s a much more internalized, self-aware experience. So, Brooke is only able to think of herself from the outside and Abigail primarily thinks of herself from the inside. In certain ways they need to vary those perspectives. It would help Abigail to have an idea of how she’s perceived by the rest of the world, and it certainly would help Brooke to think about her interior self.

C: Do you see Brooke as a cautionary tale?

ESJ: Yes and also no. There is value to becoming part of a collective, so she’s not wrong to blend into the background. She probably needs to examine what she wants and not just adopt what other people have placed upon her. There’s a level of dissociation to her that we don’t see with anybody else. She’s a cautionary tale in that you have to, at some point, find a community defined by what you need. Brooke will not let herself think about the world in that way. She’s so obsessed with running away from the circumstances that defined her that she never figures out a way to stop doing that. She’s a cautionary tale about what it means to run away from yourself. And we’re all doing that to some extent. And we all need to, to some extent. But you also need to open yourself up to the idea that who you are is worth embracing on some level.

C: In the chapters leading up to the election And towards the end of the book, two visual metaphors kind of come to the forefront: chalk outlines and floods. How do you see those as related to one another?

ESJ: Both images are based on the idea that nothing lasts. A flood washes everything away. A chalk outline is eventually erased. Both are about the ways in which gender and our negotiation of gender define how we relate to things. The second you decide to do something differently, things get washed away. Things get erased. People don’t think about how much our sense of self is defined by exterior factors. The flood is to some extent just society coming in on top of you. The outline is something the characters are thinking about as a metaphor: here’s a sense of self that is going to be obliterated. It’s about obliteration and that’s wonderful.

C: Helen introduces the idea that some fights are worth losing. Can you say more about that?

ESJ: I think that goodness, kindness and doing the right thing have value in and of themselves, even if the world wipes them away. Let’s say at this moment, we are entering a totalitarian fascism period that lasts for the rest of our lives, for the rest of my kid’s life. A lot of people in those situations who try to do good are obliterated. Either they have their lives destroyed or they are literally killed. That doesn’t mean the good that they did is without value. The symbol of a fight is often what’s important to keeping that light going even if you lose. The example of fighting is often all people need to keep that beacon going within themselves. That’s the point of the fight: if you choose your moments and have those fights, other people will have the other ones. You will start to build a movement. You will start to build something that lasts.

C: On that note, there are various images of interior light throughout the book. How do those speak to the dynamics occurring within and between the characters?

ESJ: I always have the image of the house on the hill in my head. Everything I write has a version of that. It’s a powerful thing to be driving through the middle of nowhere in the pitch black and see a house lit up and you’re like, “People are here, and I hope that they are all very kind and nice to each other.” What a beautiful thing it is to be in the darkness and then just suddenly there’s this light. To me, growing up was always such a profound experience to know that suddenly you weren’t alone suddenly.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.