When I was a very little girl my mother used to take me over to the neighbor’s house down the street. Susan* (*not her real name), the neighbor was twenty or so years older than my mother and had a forty-year-old son who lived at home with her. He used to take me upstairs and molest me while my mother drank with Susan and their friends on Sunday afternoons. They drank whiskey in a glass while cigarette smoke filled the kitchen, in a house that was fascinatingly clean and empty where I was led up the stairs to the man’s bedroom. I told my mother what happened, but nothing changed. We still spent Sundays there. This ritual seemed sanctioned, somehow, like a powdery aunt kissing your cheek or an older cousin who tickles too hard. It was sanctioned in the way that so many terrible things that happen to children—generation after generation—are, and it turned my generation, Gen X, into great, winged, helicopter parents who never let our kids out of our sight., We try to protect them, yes, but also, impossibly, we try to make right the wrongs that were done to us.

When I sat in the parlor of my best friend who lived across the street from the man who was molesting me, I told her mother what was happening. I told it like it was a joke, something funny that happened to me. She was horrified. She told the appropriate people, including Susan, who then put her son into a group home. She didn’t abandon him; he came home on the weekends. And so there he was every Sunday afternoon when my mother continued to bring me over to the house while she smoked and drank with his mother. Sadly, this was not the only time I was left to fend for myself while my mother retreated into the oblivion of alcohol and her own private pain. It was not the only time I begged my mother to not force me to go places where I was abused or mistreated. Abuse and neglect were part of the warp and weave of my childhood.

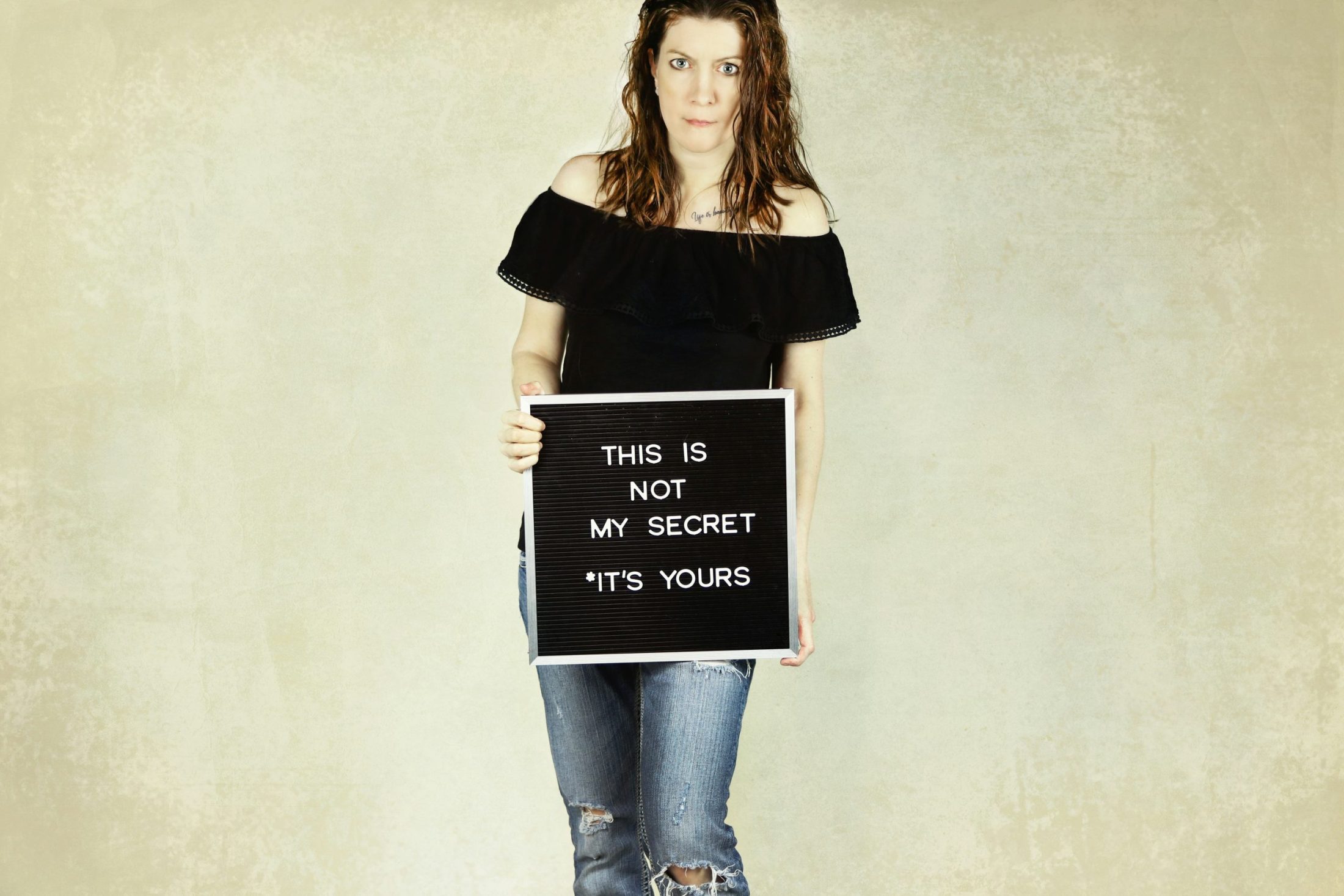

I was left to fend for myself while my mother retreated into the oblivion of alcohol and her own private pain.

When the Alice Munro story broke, I was horrified by Andrea Robin Skinner’s story, by what she had experienced and by how long she’d had to carry this awful family secret. I didn’t personally feel the loss of Munro as a literary icon because—and I guess I can admit this now that all my friends are placing her books in recycling bins—her work has never really moved me. For a moment, I thought about returning to some of the stories in the books I still have on my shelves. I wanted to return to the stories so that I could understand why her work had always left me cold. I doubt, really, it had anything to do with the person we found her out to be, a woman who didn’t just turn a blind eye to her husband’s abuse of her 9-year-old daughter, but actively chose him again and again, even after she knew all the facts and he’d admitted what he’d done.

I wondered when I read Andrea Robin Skinner’s account if Alice Munro drank, as my mother had. Drinking is a way that people live with horrific truths, about themselves and about others. I have no idea if they have this trait in common. What I do know is that they both seemed to have suffered from the kind of profound selfishness and lack of empathy that often accompanies the disease of addiction and of codependency.

My mother’s desire to drink and to numb out the world was greater than her desire to protect me. Alice Munro’s desire to stay with her husband was stronger than her desire to validate and try to repair her daughter’s pain. I don’t know the roots of Munro’s choice. I do know that my own mother drank in part because her own childhood had been so hard, marked by sexual abuse when she was a teenager—my inheritance.

Despite my mother’s difficult upbringing, she, like Munro, went on to do work that changed people’s lives. She taught public high school in Detroit and she taught with integrity and deep care, so much so that her students often sought me out and told me how much she had meant to them. Her fellow teachers drove from Detroit to the middle of nowhere town where she’d finally found peace and happiness just to pay her respects when she died of cancer at age 69. In the country where they retired, my mother was known to bring shoes right to the house of the kids whose shoes were falling apart. She brought winter coats to them that she bought in bulk from Walmart. These two women are both my mother—the one who went out of her way to bring coats and shoes to her neediest students, who never gave up on them; and the woman, who sat downstairs and drank at her neighbor’s house while her daughter was molested upstairs. In some ways, my life would have been easier if they’d been two different women—a good mother and a bad mother— but they are not. And so I’ve been left to struggle all my life with this complexity.

When I read Skinner’s essay, my first reaction was a feeling of admiration for the courage it must have taken for her to tell her story. My next reaction—which has more to do with my own family history than hers—was a feeling of sadness that she wasn’t able to tell the story while Munro was still alive. It’s not that I want Munro to suffer that humiliation for the sake of revenge, but rather, part of the enduring trauma of the abused is that so many of us are never told by the people who were supposed to protect us: I’m sorry. I should have done more. The longing for that validation never really goes away. I still feel it today, years after my mother’s death.

The longing for that validation never really goes away.

This kind of wound—childhood sexual abuse—is profound and so misunderstood that when Freud was presented with evidence of many of his female patients coming to him with their experiences of incest and child sexual abuse, he chose simply not to believe them. In fact, he came up with theories of girls seducing men and fathers, theories that helped men like Alice Munro’s second husband (who was convicted) justify his abuse. Instead of believing the women’s stories, Freud changed them to be about the fantasies of men.

Of all the painful aspects of Munro and Skinner’s story, the one most painful to me is the fact of how common a story it is—the story of women like Munro, like my mother, who are able to free themselves from so many of the constraints and injustices of a misogynist culture, but who, in the freeing, leave their children behind. And so when I think of my mother it is with a familiar mixture of sadness, rage, regret, and also, admiration and love. I did love her and she did love me and maybe that’s the hardest thing about all of this. Underneath it all, no matter how fraught and twisted the story, there is love.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.