January 21, 2025, 2:10pm

“Is it or is it not fascism” is a debate we’re going to be having a lot in the next few years, I’m afraid. And while there is perhaps an intellectual rigor to sussing out an answer, there are also things that are what they appear to be. Yesterday was a grim parade of slaps in the face, especially from the bossists (to borrow a term from John Ganz) like Elon Musk, who threw out two enthusiastic Nazi salutes.

(Sidebar: if you’re inclined to apologize for Musk, and see his heils as some sort of awkwardly bungled gesture, I encourage you to try the same arm gesture in public, and see how it’s interpreted. And if you’re still on the fence, consider that the Nazis aren’t confused.)

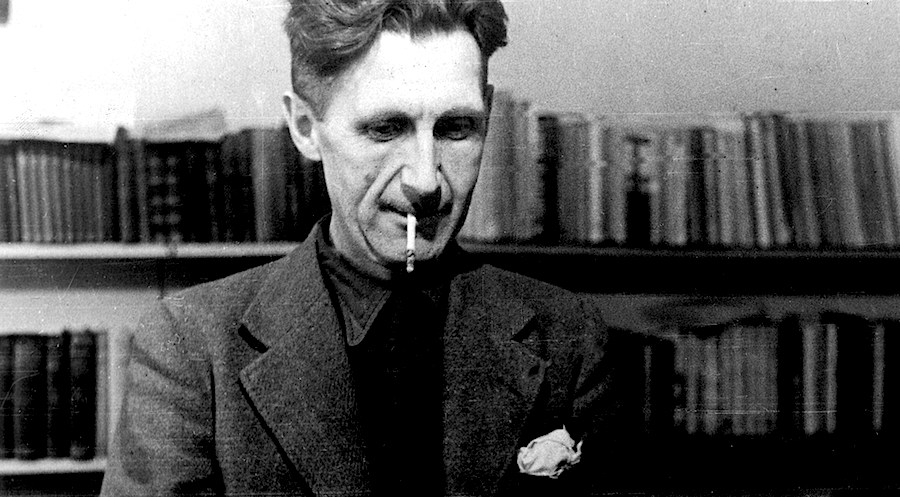

Someone who was always clear-eyed and articulate about fascism was George Orwell, who died 75 years ago today. A brilliant writer and a committed leftist, Orwell knew that the fight against fascism would be fought with both our ideas and with our bodies. His convictions brought him to Spain, where he joined the international brigades fighting against Franco. As he wrote in Homage to Catalonia:

When I joined the militia I had promised myself to kill one Fascist—after all, if each of us killed one they would soon be extinct.

He saw the power of a revolution, especially in Barcelona, before the infighting and Stalinist reprisals:

It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle … There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for… Above all, there was a belief in the revolution and the future, a feeling of having suddenly emerged into an era of equality and freedom. Human beings were trying to behave as human beings and not as cogs in the capitalist machine.

The experience of the war was not a positive one for him by any means—he was shot in the throat, after all—but it left him a much more committed democratic Socialist and antifascist. In “Why I Write”, he emphasizes that “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.”

Orwell’s political analysis saw not only that many people would be crushed under the tread of totalitarian fascism, but also, as we see today, that it would entice those who find it easier to go along, as well as those who see class solidarity and benefits to their material interests in fascist rule.

His essay “The Lion And The Unicorn” is full of sharp observations about how people contort themselves them in accommodation. Referencing the ongoing Nazi Blitz against England, he wrote,

As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me. They do not feel any enmity against me as an individual, nor I against them. They are “only doing their duty,” as the saying goes. Most of them, I have no doubt, are kind-hearted law-abiding men who would never dream of committing murder in private life.

Orwell might not have been surprised to see yesterday’s row of voluntarily subservient billionaires, either. He too saw this capitulation:

The British ruling class were not altogether wrong in thinking that Fascism was on their side. It is a fact that any rich man, unless he is a Jew, has less to fear from Fascism than from either Communism or democratic Socialism. One ought never to forget this, for nearly the whole of German and Italian propaganda is designed to cover it up.

And like Adam Serwer would later write about Trump, Orwell understood that the cruelty was the point:

Its ugliness is part of its essence, for what it is saying is “Yes, I am ugly, and you daren’t laugh at me,” like the bully who makes faces at his victim. Why is the goose-step not used in England? There are, heaven knows, plenty of army officers who would be only too glad to introduce some such thing.

In Tribune magazine, Orwell even anticipated our current predicament stemming from an overuse of the term: “the word ‘Fascism’ is almost entirely meaningless,” he wrote in 1944. But this doesn’t mean he was unclear about which side to take, writing in Homage to Catalonia:

I have no particular love for the idealized “worker” as he appears in the bourgeois Communist’s mind, but when I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on.

It’s worth noting too, that Orwell was not a pessimist, nor an ascetic. He saw the beauty and the hope of a revolution to come, writing in a book review that,

In England, a century of strong government has developed what O. Henry called the stern and rugged fear of the police to a point where any public protest seems an indecency. But in France everyone can remember a certain amount of civil disturbance, and even the workmen in the bistros talk of la revolution—meaning the next revolution, not the last one.

In short, he enjoyed life, and saw his struggle as on behalf of the things that made life beautiful. Writing of his fellow Englishmen in “The Lion and The Unicorn”: “We are a nation of flower-lovers, but also a nation of stamp-collectors, pigeon-fanciers, amateur carpenters, coupon-snippers, darts-players, crossword-puzzle fans.”

Rebecca Solnit writes about this side of Orwell, who loved gardening and flowers, in her excellent Orwell’s Roses, a collection of essays inspired by a chance encounter with Orwell’s rose garden. I highly recommend the book, not just for Orwell fans but for anyone who’s looking for inspiration in this moment, when we’ll need both bread and roses.

Orwell is an endless well of inspiration for me, but we don’t have to reach across the Atlantic to find motivation for the struggle ahead. America has always had a robust legacy of antifascist resistance. Alongside Orwell, Black Americans saw the fight in Spain as part of their fight, conceiving of a “Double V” before and then during WWII: a victory over fascism and white supremacy abroad and at home too. Many Black Americans flocked to the antifascist fight earlier than their fellow citizens, seeing that “fascism was Jim Crow with a foreign accent,” and later that “Jim Crow segregation and the Nazis’ master-race theory were two sides of the same coin,” as Matthew F. Delmont notes in his excellent Half American.

The legacy of antifascism in America has always been most robust amongst those who felt it most directly: Marsha P. Johnson, Kwame Ture, James Baldwin, and others were always clear-eyed about the struggles required, and where the loyalties of powerful Americans would settle most comfortably: alongside the cruel and venal. May they all soon be extinct.