One of the first, if not the first, published bits of Black, gay prose—and for all intents and purposes and for the remainder of this book, when I say “gay,” I mean almost exclusively “gay cisgender male”—was Richard Bruce Nugent’s “Smoke, Lilies and Jade.”

Article continues after advertisement

One passage opens with the main character, Alex, searching in a field “on his hands and knees,” until he finds at last “two strong white legs…dancer’s legs…the contours pleased him…his eyes wandered…on past the muscular hocks to the firm white thighs…the rounded buttocks…then the lithe narrow waist…strong torso and broad deep chest…the heavy shoulders…the graceful muscled neck…squared chin and quizzical lips…Grecian nose with its temperamental nostrils…the brown eyes looking at him…like…Monty looked at Zora…his hair curly and black and all tousled…and it was Beauty…”

This short story was published in 1926 in the first and only issue of the nevertheless highly influential Fire!! magazine, which was founded and filled by some of the greats of the Harlem Renaissance. Alongside poetry, plays, essays, and short stories by Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, and Wallace Thurman sat Nugent’s gay‑ass prose. Openly gay. Openly ass.

A lot of the Harlem Renaissance luminaries were queer in some way, but it was an aspect of their lives that was often obfuscated in their work and in their later biographies. Subtitled “A Novel, Part 1,” “Smoke, Lilies and Jade” is, as a work of literature, a’ight. Nugent wrote it when he was twenty, and it reads like something I might have written in college. While some writers do amazing work at that age, I was not one of them, and neither was Nugent. No tea; no shade; no smoke, lilies, or jade.

I’ve learned to love being Black, to love being gay, and to love the densely layered and beautifully textured nexus of both identities.

The story is all very stream of consciousness with no proper sentences, just clauses separated by ellipses, the kind of novelistic experimentation that seemed to be all the rage back then—with the previous year’s Mrs. Dalloway among the best examples—but Nugent didn’t have the range to pull it off, not yet anyway. Still, Nugent does have a poetic lilt to his words that’s appealing, and one wonders what the rest of this novel could have been had he finished it. And it’s a good story—it would’ve gotten an A in college, and it made the single issue of Fire!!, where it fits in perfectly as part of that magazine’s manifesto to give voice to the young, radical Black creatives shaking the tree of American culture out of a few square blocks in New York. Therefore, as a work of transgressive art, “Smoke, Lilies and Jade” is fucking astounding.

The story’s protagonist, Alex, a clear stand‑in for Nugent, is a struggling artist, living with his mother and chronically unemployed, though he also happens to be close consorts with people named Zora, Countee, and Langston. Alex is bisexual— but is she, though? He’s ostensibly in a relationship with some poor girl named Melva, but he’s completely obsessed with this white boy Adrian, whom he calls Beauty. He claims to be in love with Melva, who, it seems, is also white, but he fixates on Beauty. An entire passage is dedicated to Alex and Beauty lying in bed together, the sleeping Beauty’s hair tickling Alex’s nose as he smokes beside him, all the while wanting to kiss his beautiful lips.

Again, this is something I might have written in college, or in those wandering years after I had dropped out, when my desire gnawed at my insides and the only reprieve was the fictions I constructed around beautiful white boys. Once I finally started getting it in, as the kids say, I was able to turn the fictions into reality and wrote those moments as memories in my head. I came to understand why so many gay writers delight in describing the nape of a man’s neck; the softness of their hair and the way it decorates a pillow; the soft, soft eyelashes veiling secret treasures of the world; the parted lips aching to be kissed; the skin always white, always white, always white.

So much of gay literature fixates on white male beauty (and its destruction)—from Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray to James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room to the seminal gay novels of 1978 to Alan Hollinghurst’s The Sparsholt Affair. So much of anything intended for a gay audience fixates on and exalts white male beauty. Is it any wonder, then, that I have always fixated on and exalted white male beauty, when the things I sought to teach me how to be all taught the same thing: that white boys are beauty, white boys are desire? It all comes down to fucking white boys.

*

I came to America in 1990 from Guyana, a tiny island‑nation off the coast of Africa. Just kidding, it’s a mostly landlocked country in South America, but I had you going there for a minute. America blew my stupid four‑year‑old mind: Cable television? Are you fucking kidding me? Malls! Food that was fast and, I assumed, good for you—otherwise, why would they make it so cheap and readily available? It’s not like Guyana was “the third world” when that was still a legitimate way to describe countries—after all, noted white American man Jim Jones seemed to like it enough…too much, some might say—but it certainly wasn’t the first world. I don’t have any memories of it, really, but we didn’t have HBO. America was so rich and white and big and loud compared to the mostly Black and brown, very poor, pretty small land of my birth. I hadn’t quite figured out what being gay was, but I did have a tacit understanding that whatever it was, to quote the great Valerie Cherish, “I’m it!” And I should probably keep quiet about it.

But I fell in love so easily with men. Men in magazines, on television, in film. They weren’t all necessarily white men, but being that most of the men anywhere were white, they tended to be. My first loves were Saved by the Bell’s Zack Morris and Blossom’s Joey Russo. My mother loved her daytime soap operas, and so did I, because soaps had a reliable stream of shirtless hunks who were always just coming out of the shower or just about to put on a shirt or just lying around suggestively naked after making softly lit love to a woman. And then I started to fall in love with men in real life.

In school, my first crushes were almost all white boys. There was Jake Capella, my tall, lithe, athletic bully who was my main antagonist throughout middle and high school, but, what can I say, I love a challenge. I was obsessed with every inch of him. He had this protruding Adam’s apple I would catch myself ogling during our classes together. Jake would always make fun of me, but not in as cruel a way as some of the other kids. But he was persistent. He would make fun of my weight or my glasses, but I secretly appreciated his attention. God, that explains so much of my dating life.

Jake loved coming up with nicknames for people, and because of his humor and force of personality, they often stuck, even if they initially seemed cruel. Our mutual friend Stefan became Buff because, Jake observed one day, his hair made him look like a buffalo. Dan became Sucio, Spanish for “dirty,” because, Jake said, Dan’s house was dirty. Once he learned my middle name was Fabian, Jake started calling me Pheebs, like Lisa Kudrow’s character on Friends. I got off pretty easy, though Jake took every opportunity he could get to roast me. Sometimes I’d fire back, but I learned the best way to deal with him was just to laugh along. If we were both laughing, then I was in on the joke, and maybe Jake would like me more.

This was the same Jake about whom I wrote secret fan fiction and daydreamed. One day, I hoped, his animosity would turn to admiration. When Netflix’s British dramedy Sex Education premiered in 2019 with its love story between the openly gay and Black Eric Effiong and his tall, lithe, athletic, and very white bully Adam Groff with his protruding Adam’s apple, the sad fifteen‑year‑old faggot inside me that I will always be cried just a little. Or a lot.

When I first discovered “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” it came as both a relief (Oh, Black boys have been pining after white boys for at least a century!) and an indictment (Oh…Black boys have been pining after white boys for at least a century…). Nugent’s love story was groundbreaking because it was queer and interracial at a time when both were taboo and/or illegal. There would be other gay stories and novels throughout the twentieth century, but very few with a Black protagonist, and very few that rapturously praised and exalted Black male beauty. Sure, there were copious references to big Black dicks scattered among the gay literary canon, but where was the rhapsodic, poetic appreciation evident in the books I devoured to get a better understanding of who I was and what I could be, of Black features, of Black skin, the napes of Black necks, of Black hair, eyelashes, and fingers?

James Baldwin came out with what many consider the greatest gay novel, Giovanni’s Room, in 1956. Despite being authored by a Black gay writer—really, the Black gay writer—it’s about two white boys. Baldwin later said that Giovanni’s Room was too crowded as it was with the gay shit to bring in the Black shit: “I certainly could not possibly have—not at that point in my life—handled the other great weight, the ‘Negro problem.’ The sexual‑moral light was a hard thing to deal with. I could not handle both propositions in the same book. There was no room for it.”

It was 1956, so he had a point. Nugent didn’t have to, or didn’t feel the need to, handle the “Negro problem” with his scant short story, which is less about being Black and more about being a young artist in love. Baldwin would try to handle both “problems” in 1962’s Another Country, though his Black queer protagonist (spoiler alert!) dies by suicide early on in the book and said protagonist’s gay lovers are all exclusively white. And like his characters in Giovanni’s Room and Alex in “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” Baldwin’s queer male characters in Another Country are not gay but bisexual. As if Baldwin and Nugent were hesitant to go full‑blown gay, something their white counterparts were less worried about, because, one assumes, they could be. Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar came out in 1948, and its protagonist, Jimmy Willard, is a big old corn‑fed all‑American faggot. By the time he got to 1979’s Just Above My Head, his sixth and final novel, Baldwin is still killing his Black gay darlings, but his protagonist, Arthur, doesn’t hide under the slightly more respectable(?) guise of bisexuality, and he actually has love affairs with Black men.

To be Black and gay is to have to deal with the implications of your desire.

Still, Just Above My Head isn’t strictly a gay novel, just as Another Country isn’t. Baldwin is more concerned with handling the great weight of American morality as it relates to Blackness, as it relates to queerness, but he could never be Black or gay enough for everyone’s taste. Eldridge Cleaver famously wrote of his dislike of Another Country, particularly its depiction of interracial homosexual desire, referring to it as a “racial death‑wish” in his 1968 essay “Notes on a Native Son.” Cleaver writes that “Negro homosexuals” are simply “frustrated” that they can’t have babies with a white man and so they end up “bending over and touching their toes” for them, leading to “the unwinding of their nerves” and the further “intake of the white man’s sperm.”

Yeah, but, sis, I’m a top. What about the white man’s intake of my sperm?

*

I’ve fallen in love with so many white boys over the years. If not love, at least lust. It was never truly love—that remains elusive. But whenever I imagine myself in love, it’s always with a white man. I’ve dated (read: slept with) men of all backgrounds because I’m an equal opportunity slut, but in my heart, I think I will, I want to, end up with a white man. And that thought has haunted me since its realization. Why wouldn’t I want to fall in love with a Black man? Or any non‑white man? Why does the ideal man of my dreams have to be of a certain race at all? I’ve had to interrogate my own desire and the immense guilt around it since I crushed on Jake Capella a quarter century ago. His very whiteness informed my perception of him, as my tormentor and oppressor, as something unattainable, as someone so unlike me in so many ways.

I used to think that my attraction to whiteness was a reflection of some inner self‑loathing, but if I’m being honest, I’ve developed a really unhealthy obsession with myself. Like, a bitch has got it going on twelve ways from Sunday. This is, however, an act of overcompensation. If I don’t believe that I’m, with all due respect to Trina, da baddest bitch, it’s only a matter of time before I backslide into questioning if I’m even a worthwhile human being. I’ve struggled with accepting my Blackness like I think a lot of Black people in America have, especially when you’re told, either implicitly or explicitly, through language or legislation, through history or an attempt at erasure of that history, that you’re not good enough.

Then to be queer on top of that is to invite even more of society’s ire, to shoulder even more of the burden for the ills of the world, to feel as if your very presence is a blight on humanity. If you’re not surrounded with any sort of counter-programming—be it love or art or some sort of passion—you’re likely to believe these lies told about you. As I got older, the culture around identity changed enough to provide some of that much‑needed counter‑programming, but more important, I just got older.

As an adult, you have some agency, albeit very limited, in defining what life is and how you fit into it. By the time I got to that point, I had already been questioning everything, all the lies—so then I had to figure out what the truth was. I’m still figuring that out, but in the figuring out I’ve learned to love being Black, to love being gay, and to love the densely layered and beautifully textured nexus of both identities.

It’s just really hard sometimes. A lot of the times. To be both, and not to feel enough of either. To not be Black enough for Black people, and to feel like an outsider among the gays, an outlier among those who should be your community, your peers, your family. No matter how comfortable I am in my own Blackness, I feel it will always be questioned, by both Black and white people, because I don’t conform to a certain understanding of what a Black man is or should be. Black folks have their own ideal, and white folks theirs, and they are as different as night and the morning three weeks hence. I don’t know where I fit into either of these archetypes, nor do I particularly care to fit into any archetype whatsoever.

I imagine myself getting a white boyfriend and secretly admonishing myself for being yet another Black boy living his little white‑boy fantasy. But being with a white man would grant me a form of legitimacy among the gays, a social escort through the machinations of gay life with which I never felt comfortable in the first place. With my token white boy, I would be granted the legitimacy of existing in the same predominantly white and white‑controlled spaces not as an intruder but as something more than a guest. (Though I would never make the mistake of believing that I actually belonged.) In dating a white boy, however, I would risk losing further legitimacy among Black people, gay or not—either in actuality or just in my own eyes.

Suspicion always follows a white person among Black people. Not so much hostility as a genuine wondering of What’s going on here, and who invited you? So I’m not just worried about what everyone else thinks, and that’s none of my business anyway. I worry about what I think of myself and what dating a white boy says about me. Am I not enough? Is my Blackness not enough? Am I betraying my race? Am I just another stereotype? The great weight, indeed. To be Black and gay is to have to deal with the implications of your desire. When all I’ve ever wanted was to be in love. Yet, love remains elusive because I keep it at bay, out of fear of my own desire. I shouldn’t desire whiteness; therefore, I shouldn’t have love.

__________________________________

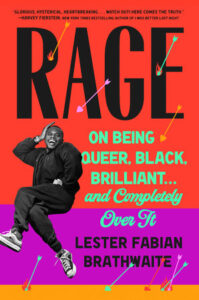

From Rage: On Being Queer, Black, Brilliant…and Completely Over It by Lester Fabian Brathwaite. Copyright © 2024. Available from Tiny Reparations Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.