This is not a normative biography linearly dragging you from a cradle to a grave” writes self-described “queer Black troublemaker” Alexis Pauline Gumbs, whose new biography of Audre Lorde attempts to trace the life of the pioneering Black feminist thinker through the land, air and water that surrounded her. Gumbs takes her lead from the smallest details of Lorde’s poems and the earthly conditions that influenced her: she uses “supernovas, geological scales of transformation and radioactive dust” to give shape to the events of Lorde’s life, maintaining that “the scale of the life of the poet is the scale of the universe”.

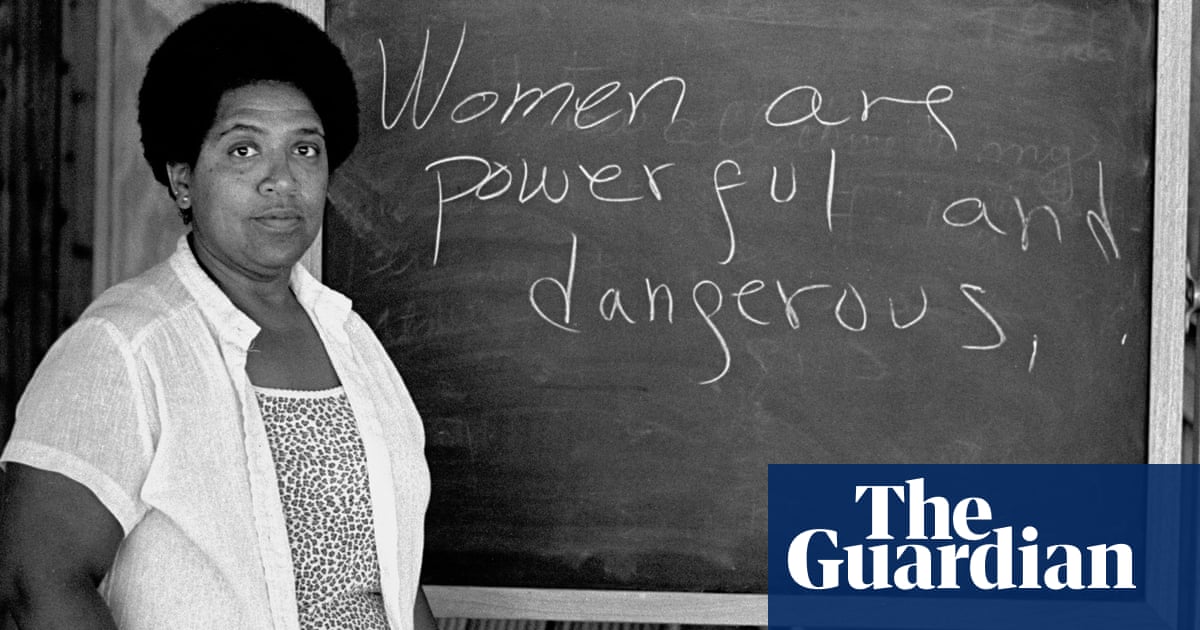

In doing so she reckons with an under-theorised element of Lorde’s poetry – her consistent engagement with nature. Gumbs asks: how might we think of Audre Lorde, not as a hollow symbol of Black feminism, but as a thinker whose own survival in a world premised on her extinction required her to take up the task of self-defence through poetry and political action? She approaches Lorde as one would a mentor, mother, sister, auntie, lover – with curiosity and mutual respect, through 58 fragmentary chapters to be approached by the reader in any order.

For Gumbs, Lorde’s life is not yet over. In fact, at various points she invents her anew using speculative narrative, rescuing her from the fixity of history. She writes that, at her own funeral, Lorde “squeezed her longtime partner Frances’s elbow,” “made her colleague Johnnetta Cole laugh out loud” and “whispered in Gloria Joseph’s ear”. Throughout the book, Gumbs hints that Lorde is always there, watching over a new generation of Black feminist theorists, artists and practitioners.

Two decades since a long-form biography of Lorde was published by Alexis De Veaux, Gumbs’s own mentor and a student of Lorde’s life partner Joseph, she experiments with the form, taking seriously the idea that one cannot understand the individual or their social world without a thorough analysis of the earth that hosts them. Gumbs weaves materialist Black feminist political analysis with lessons we might learn from the non-rational: animals, hurricanes, all the warning signs emerging from a planet being destroyed by fossil fuel corporations.

Gumbs’ reflections on the events of Lorde’s life are always grounded in the political forces that produced her. She writes that Lorde’s generation emerged “during the precarious period between two world wars on a planet reeling from the largest-scale man-made death event recorded up to that point” and that this historical moment produced a “bellicose baby”, a rebel, a woman who rejected authority at every possible juncture.

This two-pronged approach means that Lorde’s staunch anti-imperialism, solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for self-determination, critiques of capitalism and patriarchy are not subsumed by Gumbs’ admiration of her poetics. In fact, she is determined to demonstrate how Lorde’s creative work can never be separated from her political convictions. For example, Gumbs notes how Lorde’s exposure to the racist nursery rhymes in Arthur Rackham’s Mother Goose and the work of English poet and writer Walter de la Mare shaped the form, rhyme and metre of some of her earliest fantasy poems.

Moving beyond an attempt at straightforwardly reconstructing events in her life, Gumbs disintegrates, rearranges and examines all the matter that created Lorde, enabling her to unearth the many layers of feeling evoked by her lesser known poetry. She emphasises Lorde’s continued presence, wrestling her legacy away from the grip of diversity and inclusion initiatives, and situating her in rapidly changing and violent worlds, both past and present.

Gumbs’ rigorous – if sometimes overly effusive – engagement shows what it means to think about life and work as connective tissue. Her writing mimics the tempo of the breathwork she practices, with some passages written like long, slow inhalations, with the turn of a page prompting an an exhale. Ultimately, she shows us the kind of complex and radiant scholarship that emerges when scholars dig deeper, refusing to treat the life and work of Black feminist figures as self-evident.