In the weeks that followed the horrific attack on October 7th, we saw as one of the largest movements in American history rose up to stop the incoming genocide in Gaza. To date, Israel has killed at least 40,000 people in its unprecedented campaign in the small, two-mile wide stretch of land, destroying civilian, political, and health infrastructure, and acting as one of the largest dispossessions of Palestinians since Israel’s founding in 1948.

In response, anti-Zionist and Palestinian solidarity groups around the country came together to demand a ceasefire and an end to U.S. military aid to Israel. Jewish-led groups were at the forefront of this, with the nearly 25,000 member organization Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) as the most notable as they held demonstrations, blockades, and civil disobedience in cities from coast-to-coast. JVP has been an established project in fighting for Palestinian rights, in normalizing anti-Zionist Jewish identity and pushing the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction (BDS) movement to demand Israeli accountability and the end of the occupation of Palestinian land. In doing so, they have become notorious in many Jewish circles, where association with JVP can be enough to have relationships with mainstream Jewish organizations completely severed.

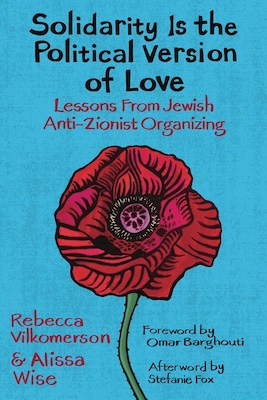

In its nearly 30 years of life, JVP has reshaped itself to accommodate a growing and changing demographic base, taking on new strategies and evolving to highlight underrepresented Jewish voices and those often left behind by both the left and the Jewish establishment. Two former staff members were at the heart of building the organization during the first two decades of this century, and helped to see the organization from its early days as a mostly California-based group to the evolving powerhouse it has become today. In an effort to chronicle the lessons they learned in their time in leadership at JVP, Rabbi Alissa Wise and Rebecca Vilkomerson have published a new book, Solidarity Is the Political Version of Love: Lessons from Anti-Zionist Jewish Organizing, that looks back on what they learned from years organizing one of the most direct, and divisive, organizations fighting for justice.

We talked with Vilkomerson and Wise about what motivated them to write this book, what experiences they had in building JVP that might be instructive for others considering what it takes to change the world, and what those lessons mean for one of the most significant moments in the entire history of the conflict.

Shane Burley: When I was reading this book what stood out was that this was a real organizer book, meaning that it jumped into the nitty gritty of how movement building works and the lessons you walked away with from your work in Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP). What made you focus on the practical activist work when you were considering how to tell your story?

Rebecca Vilkomerson: The reason we want to talk about organizing, first of all, is it doesn’t get talked about that much. The mechanics and the specificity of it. The book is about and for the Palestine movement, but we actually also wanted it to be much broader, so we talked with folks at organizations like Showing Up for Racial Justice and Hindus for Human Rights. And there’s a very specific kind of organizing of when you’re trying to shift your own community’s perspectives and where part of your fight is within your own community.

Some of it is specifically for organizers, but we also hope that it’ll reach people more broadly who are thinking about moving from activists to becoming organizers. I think now, especially, all these new people are coming into the Palestine movement and need leadership development and political analysis and strategy. All of those skills and questions are critically important, and that is what a lot of people are thinking about now as they consider the political crisis we are in.

Alissa Wise: When we were pitching the idea to Haymarket Books and were in conversation with them about what the book could look like, we discussed how the organizing approach we practiced in JVP is often more durable and long-term and can offer broad lessons.

There has been a trend of emergent organizing that has less staying power in terms of building power over time, versus the approach that JVP has often taken that requires digging in over time. With everything from developing member leaders, campaigning, and building organization, the model we have worked with is both institutional and flexible so we can evolve as the political winds change. This is another important piece for the Left, to build and sustain enduring organizations that are not static and ossified, but instead incredibly responsive. From our reading of organizing history, this has been an important part of what has allowed movements to thrive over time.

SB: There are a lot of different elements to JVP’s approach, from both being a mass movement organization and a kind of non-profit, to being a Palestine solidarity organization but also a place where a lot of people reclaim, or redefine, their relationship with Jewish identity. How did you balance these different components of the project together when you were building it up to the movement it has become today?

RV: We name this in the book, that the productive tensions of the organization always living in what we call “both/and” situations, which are present in the examples you mention. Especially as we matured in our leadership, we were able to name these tensions with our staff and members. You shouldn’t pretend that those contradictions don’t exist and instead want to live with those tensions and be responsive to them. The truth is, sometimes we got that balance right, and sometimes we didn’t. We used a few examples in the book when we felt like we balanced them in the right way and where we erred on the wrong side and, hopefully, learned from it.

AW: One of the important takeaways from the book is that we never had a strict solidarity model where we are essentially there to do what Palestinians ask us to do. It was a more complicated solidarity model where we understood that we have these serious accountabilities to Paletinians and ingrained ourselves into our work in the organization. But, at the same time, we were clear that there were Jewish communal concerns that were part of our obligation and mission. There is work that has to be done in the Jewish community that is a venn diagram with Palestine solidarity work, but is actually separate from it. And that was always a tension. So for me personally since October 7th I have focused on picking up the side of the venn diagram that doesn’t fit squarely in JVP, which is the project of building a Judaism outside of Zionism. That is important, but it’s not the same thing as JVP’s organizing model. For a long time, JVP was trying to do both and it does get messy. I think the way we navigated it was we tried things, some worked, some didn’t. Jews are implicated in this but are not the victims of Israeli oppression the way Palestinians are, and there is an injury to the Jewish community in this. So this tension remains so you have to take each choice as they happen and weigh the pros and cons of different priorities and tactics. This is one of the ways in which identity politics and solidarity politics rub up against one another.

SB: Who do you think the primary audience is for JVP? Are actions and strategies meant to target primarily those in the Jewish community, or do you use your positionality to move politics beyond Jewish organizational life?

AW: It’s interesting you use the word “audience” because we review several examples in the book where JVP was instrumental in achieving actual, tangible victories in the movement because of our position as Jews in solidarity with Palestinians. But that’s different from the audience because that positionality is about who we are working with. But when you say audience I think that’s true, but as organizers we are always trying to reach the people who are setting the tone for the Jewish community with actions, but it’s those who are participants in Jewish culture who are movable that we want to invite in. So there are the legacy Jewish institutions that might be the audience, but it’s the members of those organizations that we actually want to come into our ranks.

RV: This gets back to the “both/and” analogy. At different times we had different, though complementary targets and/or audiences. Early on (even before I was on staff) we had an approach, which later was echoed by IfNotNow’s strategy. In the early 2000s in San Francisco, we applied to be part of the Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) and were shocked that we weren’t accepted. We wanted to be a part of the larger Jewish communal infrastructure and they didn’t want us. And that continued as our politics sharpened, where institutions like Hillel excluded anything JVP related. So at a certain point we were like fuck them, we will create our own Jewish institutions that reflect our whole selves. That was an evolution. Our job was not to reform the Jewish world from the inside, but to build a whole new one. So we were still often speaking to the Jewish community, but also creating space for Palestinian voices and other people who wanted to speak for Palestinian liberation but were silenced by weaponized accusations of antisemitism.

SB: There seems to be a debate happening in the anti-Zionist world about how much collaboration or even relationship is possible with larger Jewish organizations that generally have some degree of a pro-Israe consensus. So, for example, if an organization like JVP is allowed to hold an event at a Jewish Community Center, that may be a victory since they were able to get past the censors and will be able to reach a larger Jewish audience often kept away from them.

But at the same time, there’s also a push to build Jewish life completely outside of these institutions. To build new synagogues, community centers, even a sense of Jewish identity that doesn’t fight for its space in the mainline Jewish world, but on its own terms completely. How do you think about this negotiation, and are those two strategies actually at odds with one another?

AW: I have a dream to start a new movement of Judaism, a truly new stream of Judaism that we would establish, which could supplant the existing ones. I was recently talking with a group of rabbis about it and pitching my idea and one of them really took issue with the idea of “supplanting.” He said that we don’t want to supplant them. We have lots of people that are inside of these institutions that are moving them on these issues and that’s actually really important work. So we had a philosophical conversation about what we’re doing, and what it means to sort of create an alternative that can somewhat replace some of those old institutions in the lives of many Jews. And, if successful, this becomes the future of American Jewish life. So then the question is, how do we do that if we aren’t trying to replace these existing organizations.

Our job was not to reform the Jewish world from the inside, but to build a whole new one.

—Rebecca Vilkomerson

The aesthetics of this is part of the problem because people also enjoy the rebellious nature of building a new project, which they sometimes don’t want to then become the status quo. This can also be part of the conversation around projects like Rabbis for Ceasefire, which I co-founded, where some anti-Zionists will pose the question immediately about why all the participants aren’t themselves openly anti-Zionists. And this perspective can miss the reality of the organizing work involved, which is that you don’t get everybody on board right away. Not everyone comes into this work exactly where you, as the organizer, might want them to be. So part of my hope for this book is that it will create a space for us who are in conversations with our local communities about these issues so we can ask that exact question of the difference between just mobilizing supporters and organizing a community so as to move them along on an issue.

This means asking people: what is your vision of change is you are looking for, what the Jewish community could look like. Do you want to change organizations or do you want to build new ones? Do you want these older institutions to disappear so new ones can take their place? And I think right now we are not at that level of discourse because of the aesthetics of activism that are playing out right now.

RV: I don’t disagree, but also it takes two to tango. Alissa has an incredible vision for Judaism beyond Zionism, but that’s also a different question than the viability of the organizations that have taken control of Jewish life now. And with the way that mainstream Jewish organizations treat us, there is not necessarily a pressing threat of cooptation right now. We are so far from that. So we should just be aware that there isn’t just an aesthetic of being told we don’t belong, but actually we’ve been told over and over again in often the most hateful ways possible that we don’t belong and in ways that are incredibly hurtful on purpose. This is more personal than strategic, but I struggle being in relationship with any group that has not called for a ceasefire. I feel like we may not hold many values in common.

SB: We’re also talking at a really heightened moment where people are drawing really sharp political lines, often because the moment seems so dire as the genocide continues in Gaza. But sometimes these choices are different from strategic ones that we need to make as part of long-term movement building. What kind of strategic lessons do you have from your experience of organizing in other moments of heightened emotions that might be helpful today?

RV: This returns to “both/and” and the ongoing productive strand of debate that has continued through JVP. Instead of spending all of our time and energy in conversation with people who were still out of reach, we were able to build something where people who were ready to take action could do so. That has proven strategically effective because the low hanging fruit was always Jewish people who already didn’t feel like they had a Jewish home, so connecting with them rather than moving people who would have to leave their Jewish home and come to another. So when finding people who already felt outside of Jewish life they were able to discover a new Jewish community that felt precious, beautiful ,and meaningful. So we chose to focus on the unorganized, the often unaffiliated Jews who may have affinity for our politics, rather than re-organizing those already deeply involved in existing institutions. At different times you might want to choose different approaches, and there are also different lanes within the movement. For example, right now JVP can be a container for those who are ready and Rabbis for Ceasefire is creating a place for people who are in process of changing their politics. You can have both of these strategic options.

SB: With some of these mass protests over the past year led by leftist Jewish organizations like JVP, there is a question about whether or not we are seeing a resurgence of the Jewish left. Do you think that something distinctly new is happening right now, or is this just the continuation of the work that has been happening for years?

I became a rabbi in the first place, because I want to make sure that there is an ethical, liberatory Judaism for future generations.

—Alissa Wise

AW: It could be that what you’re noticing is a really good development in that people are noticing that Jewishness as a category is genuinely under threat by the ways that it’s been completely conflated with Zionism. And that it’s actually strategically expedient for people who identify as Jews to be able to draw the distinction between Zionism as a political project and Judaism and Jewishness as a religious and cultural tradition. The debate on that conflation has steadily had the volume turned up, because of JVP’s shift to being anti-Zionist and debates around antisemitism definitions like the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition, which has been used to stifle pro-Palestinians speech, has brought it into focus more.

RV: This is beyond just the question of the Jewish left: there has been a return of the left in general. The left is undeniably stronger than it was, definitely ten years ago, probably even twenty years ago. Since the late 1960s, even. So the Jewish left is a part of that and responsive to that. So we were always here, but we weren’t here in the size and prominence we are now. A big part of that, like Alissa was talking about, is that there are multiple conversations happening right now about how to build Jewish communities beyond Zionism institutionally. This has existed for a long time, but to have enough strength, power, experience, and ambition to be able to put a name to it and build institutions is a different stage in this.

AW: I was having lunch with a friend and we were talking about this question of whether or not Judaism and Jewishness continuing is something you would feel proud for your kids and your grandkids to be a part of. Does this matter in our heart of hearts? I wonder how much of what is animating people to be involved in these projects and to show up like they have is that this is a live question. This is my motivation in life. I feel personally responsible, and I became a rabbi in the first place, because I want to make sure that there is an ethical, liberatory Judaism for future generations. And I think that possibility is up in the air at the moment. This is part of the parallel fight that’s happening right now, and it’s been simmering the past number of years. I wonder if this is what’s in the air, a sense of pressure, and obligation and responsibility to our Jewish ancestors and our Jewish family and our Jewishness itself.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.