Much of what the Civil Service does takes place behind the scenes instead of on center stage. Basic public goods that Americans take for granted, like clean air and safe drinking water, rely on a complex infrastructure of regulation and enforcement. The American way of making policy means that benefits, such as they are, are often channeled through the tax code. The political scientist Suzanne Mettler calls this invisible work “the submerged state.”

During the first decades of the 20th century, the rapid growth of the administrative state aroused suspicions. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt created new federal agencies and programs in the 1930s to address the Depression, small-government conservatives were outraged. A group of businesspeople created the American Liberty League to attack the New Deal on constitutional grounds, charging it with executive branch overreach — a “strategic choice,” says the legal scholar Gillian Metzger, who notes that any attempt to go after the New Deal for burdening elite economic interests would have been a hard sell to a suffering public. In the lurid rhetoric of one Liberty League pamphlet, “The federal bureaucracy has become a vast organism spreading its tentacles over the business and private life of the citizens of the country.”

Conservative denunciations of the administrative state have continued to couch objections in terms of the Constitution and bureaucratic treachery. In “Unmasking the Administrative State” (2019), the conservative political scientist John Marini warned that the growth of government bureaucracy “had opened up the prospect of the greatest tyranny of all.” Two years later, Trump’s 1776 Commission published a report that compared President Woodrow Wilson to Mussolini: “Like the progressives, Mussolini sought to centralize power under the management of so-called experts.”

Fears of an undemocratic, overweening bureaucracy haven’t only served as a right-wing talking point. Some of the administrative state’s most pointed critics have been intellectuals on the left, like the anthropologists James C. Scott and David Graeber, each of whom has argued that a domineering bureaucratic state is hostile to local ways of living. But anarchist critiques like theirs are harder to marshal into a mass political movement. In 2015, a time when the Tea Party, a MAGA precursor, was already well underway, Graeber lamented that the right had figured out how to politicize antipathy toward the bureaucracy, deploying the rhetoric of “anti-bureaucratic individualism” to push through a free-market agenda that guts social services while bolstering business interests.

An ‘Unrelenting, Fantastical Assault on Specialized Knowledge’

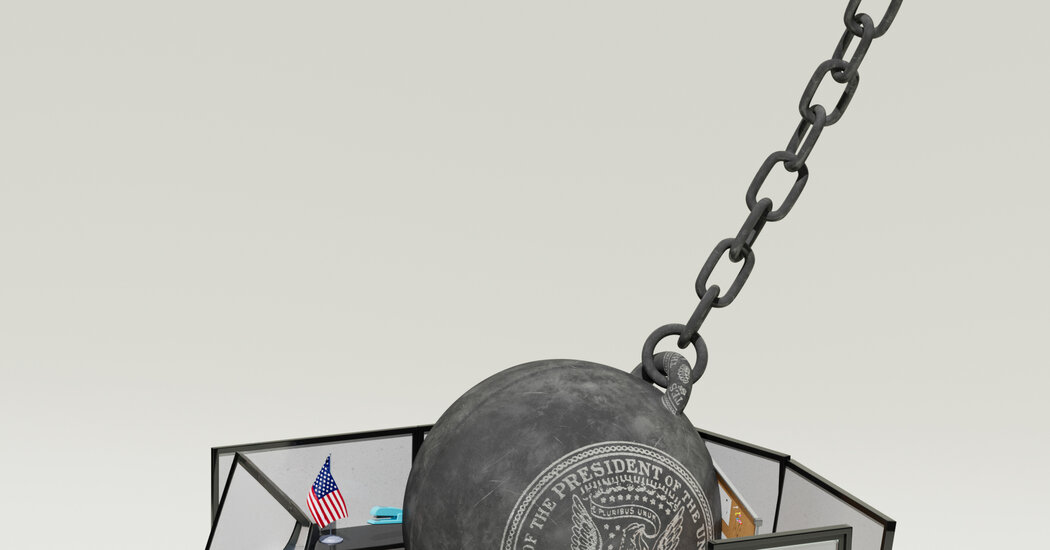

The MAGA thrashing of bureaucracy, though, is of a different order. The political scientists Russell Muirhead and Nancy L. Rosenblum distinguish between critiques of government and Trump’s vows to hobble it. “Every modern state is an administrative state,” they declare in their spirited new book, “Ungoverning: The Attack on the Administrative State and the Politics of Chaos.” They take a common complaint about bureaucracy — its inescapability — to highlight its necessity. A bureaucracy filled by professionals and experts who administer the day-to-day functions of governing is the price we pay to live together in a big, complex, populous society.