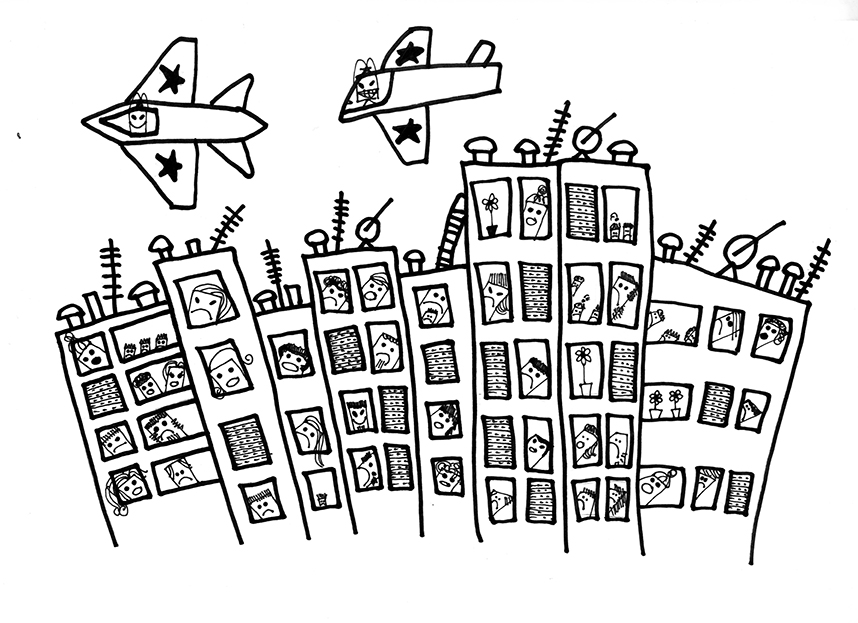

Until that day I thought you could only hear such a sound at an air show, when the planes in the sky left blue, white, and red trails and the pilots performed breakneck stunts like Tom Cruise in Top Gun. Except on this particular day, all the Tom Cruises were wearing the olive-green uniform of the Yugoslav People’s Army.

Article continues after advertisement

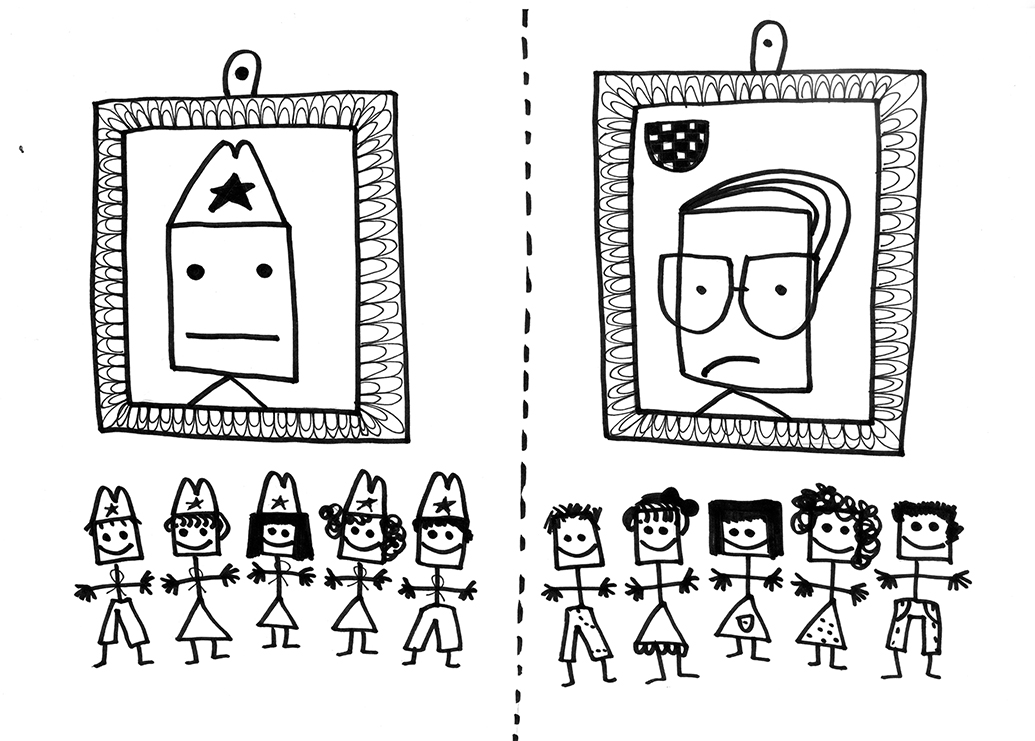

I’d never been to an air show, but in the sixth grade my brother enrolled in a plane-modeling class, and their comrade took them to one as a reward. Then suddenly the air shows ceased, just like we were no longer allowed to call our teachers “Comrade!” Everything was repackaged. Including the word “comrade,” which was folded into “Mister” and “Miss.” And while we’d lavishly been inducted into the Yugoslav Union of Pioneers, there was no pomp or circumstance when the time came for the upgrade in rank to the League of Socialist Youth. At school, Tito’s portrait was replaced by the Croatian coat of arms and the crucifix. Mass was no longer held in a two-bedroom apartment off Bolšić Street but in our school lobby. Our school was no longer named Branko Ćopić Elementary after the Yugoslav writer but “Island Elementary,” and we no longer went on field trips to the Yugoslav Pioneer City but to an ancient Croatian castle or some such thing up north. Most of my friends with newly out-of-fashion names—Saša, Bojan, and Boro—moved away overnight.

All the little Yugo cars lost their Ys, while Converse high-tops gained a Croatian checkerboard taped over the star. We stopped swearing on our honor by Tito’s “little key” (whatever that was) and dropped the Communist Partisan Rade Končar star trick from our jump-rope routines. And yet, maybe worst off were those guys with the dated “JNA” tattoos, for the now-obsolete Yugoslav People’s Army.

Back in the air-show days, my brother and I had a little impromptu gang—“impromptu” because he called all the shots and summoned or dismissed us whenever he pleased. I complied with his every demand, desperate to share in the atmosphere of him and his friends, a few of whom I had crushes on, though I entertained no illusions that they’d ever even noticed me. I knew their attention was reserved for the hot girls in their grade. Me? My mushroom haircut participated as an accessory to one of a million pitiful, glitterless corduroy outfits that two generations of women (my mother and grandmother) relentlessly sewed for me. Anyway, back then, my brother had taken an interest in books about weapons and fighter jets, and, during rare moments of goodwill, and for lack of better company, he would talk me through them. The Polikarpov I-16, the Henschel HS 126A-1, the Messerschmitt Bf 109E, and many more from the Ilustrovane istorije vazduhoplovstva (The Illustrated History of Aviation), along with a few ultramodern ones from a book in English. Even though I never found any of it nearly as interesting as he did, there was some decent stuff. Like that American plane with its snout painted to resemble a shark. My brother knew everything there was to know about planes, about weapons, armies, you name it. I could appreciate that shark plane, and moments when my brother considered me a friend.

When one day the planes became as loud as they did, it dawned on me what the air shows must have sounded like—albeit this wasn’t the first thought to cross my mind that afternoon when two planes whizzed past a hair’s breadth above our heads while we were playing in front of our apartment building. School was supposed to start the following day, so those were our last moments of joy on the raised sewage vent out front. The ensuing anxiety-ridden fall afternoons would be dictated by homework, music lessons, piano practice, and solfeggio to avoid embarrassing my mother and father in front of the music teacher, Ms. Milić. When the planes hissed past us, I was gripped by the kind of fear I’d felt when my comrade—when my teacher—randomly quizzed us on geometry, flipping through the roster and lingering near the Ks. As a matter of fact, the feeling that Sunday was much more terrifying. We scattered immediately because we were chased off by Ms. Munjeković from the fourth floor, although all the neighbors’ heads had already popped up in the windows of their apartments, including my mother’s, shrieking that I was to come inside this instant, which I would have done without her bold invitation. We used the stairs and not the elevator, like we usually would after we played. The whole building was in complete disarray, and I reached our fifth-floor apartment before you could say cakes, my heart pounding so hard I thought I would suffer a heart attack, the kind of aches my mother warned I’d have if I consumed black coffee.

My mother and father were straight-faced and agitated, but not like when they were fighting with each other or scolding us about something. Inside the apartment, the radio and television were both on and tuned to the news. And when a group of unshaven men appeared on-screen standing along barricades, and other slightly less unshaven men were shown assembling under the Croatian checkerboard with Dr. Franjo Tuđman at the fore, an air-raid siren sounded. My first-ever air-raid siren. Until then, I’d only heard the one for Comrade Tito’s death, which obligated everyone to freeze no matter what position it had caught you in. The state of affairs in our apartment now reached its culmination: my father was rolling down the shutters, my mother turning off the gas, my brother moving the birdcage away from the window. My heart began pounding again like in that would be heart attack. Then my father was telling my mother to grab their suitcase, which had already been packed several days prior and had since stood at attention in the foyer. I likewise bolted to fetch my own things, because when midnight finally struck, I, too, was, in a sense, prepared.

Over the previous weeks, I’d heard my mother and father sounding increasingly anxious on the phone with our extended family as they squeezed out every shred of news, and that year we’d skipped vacationing on the coast but for a couple of days. My grandmother and nono in Zadar seemed equally worried, and all the beaches near them were relatively deserted (there’d even been plenty of space to lay out your towel). All roads had been leading to this moment, which, albeit anticipated, was no less horrifying. Nevertheless, we had to “remain collected,” as one of our neighbors kept saying. (His name—Stevo—had recently grown out of fashion, but he surprisingly hadn’t moved away.) All this is to say that my things, which neither my mother nor father knew anything about, were also prepared. In my little Smurfs suitcase, I packed away my most prized portable property, the most important heirlooms I wanted by my side if the world ended. Should our building be struck by a bomb and reduced to ashes, spewing flames and black smoke, life would still be worth living if my Barbie remained whole, wearing her flashy little pink outfit with its tiny fluorescent lemons, pineapples, and bananas; her pink-and-green watermelon-shaped purse; her sunglasses; and the open-toe heels that completed the look. And, fingers crossed, nothing happened to any member of my immediate family, my distant relatives, or my friends from school and from our building. Leaving Barbie at the mercy of the shelling would have been a reckless gamble, and Barbie was merely one share of my wartime necessities. I mean, what was Barbie without her abundance of flawless belongings? She would be reduced to the plainest peasant girl from the Handicrafts store, and I had seen more than enough of those before the day arrived when She finally knocked on my door (to be precise, my mailbox). But that was long ago, long before all that business with the planes and the sirens. In the beginning, my mother had absolutely refused to buy me that sliver of plastic perfection, but she was talked about, she was known, and some, like one Ana F. from building #17, had even acquired her before I had. Everyone from our building had watched Her. Even though she was so small, oh, that platinum-blonde cowgirl was clearly visible in Ana’s hands. And not just visible. On the raised sewage vent where the girls from #17 played, you could just feel there was something extraordinary present, something that must have fallen from the sky. Ana’s aunt had sent her this real Barbie by airmail from America. The blonde who could bend her knees and came with a ton of accessories. Rumor had it that the folk singer Neda Ukraden’s niece owned as many as fifty! Jealousy is not the right word to express the feelings that overcame those of us who didn’t have a real Barbie. Yes, a real one. For the record, there was no shortage of wannabe Barbies made from abysmal varieties of plastic. Non-Mattel fakes with puffy cheeks, unbendable knees, poorly sewn clothes, and catastrophic shoes, who weren’t even called Barbie, but Stefi, Barbara, Cyndy—a whole gamut of stupid names. Needless to say, not having a real Barbie meant being profoundly unhappy. My uncle Ivo from New York finally put an end to this dark Before Barbie Era and sent one to our home, because, unlike all the others, he simply couldn’t let his niece in Yugoslavia be deprived of that small but important token of prestige and prosperity.

It was the dawn of a new day when she arrived in our mailbox, which my mother and I opened together. At least in that moment, despite her previous show of disinterest, my mother caught Barbie fever. I saw it in her eyes. And it honestly didn’t make me think she was any less in charge, since you would have to be blind (at the bare minimum) to remain indifferent in Barbie’s presence. This fever was marked by the realization that only a thin layer of brown wrapping paper stood between me and my most coveted piece of plastic, preventing me from even guessing which one would be my first Barbie—no less, my first real one. When I unwrapped the package, it simply couldn’t have come out more perfectly, because my first Barbie was also my favorite TV character: Krystle Carrington from Dynasty! (On second thought, it might not have actually been that Krystle, since the box had “Crystal” written on it, but this detail was immaterial and I imagined it was Krystle in the flesh.) And when I opened the box and loosened Crystal Barbie from her protective restraints, it felt like I had come into physical contact with a deity. Only this deity was much more glorious than all those fat and clumsy prehistoric goddesses that had set my corneas ablaze, given my exposure to all sorts of exhibits at the Archaeological Museum my mom and dad hauled me through in the hope that I would acquire a “cultural sense” from a very young age. Oh, that shimmery little pink ribbon tied around her iridescent, waist-defined cocktail dress, with a matching shimmery pink at her neckline; her small ring; her earrings; her little silver sequined shoes; her hairbrush and comb; the scent of fresh plastic—it was all so real! She was no longer an unattainable object in commercials on the satellite channels, inviting me to imagine for the umpteenth time that I was playing with her as if she were really mine. For the first time in my life, I had something that was truly valuable.

My next Barbie was gifted by my uncle Marko. Although the matter at hand now concerned my second Barbie and the first would always be first, my second Barbie was really something miraculous. It was only when Uncle Marko brought her, Day-to-Night Barbie, that I began to recognize Barbie’s true potential and how many additional little things could accompany one single Barbie. During the day, Day-to-Night Barbie wore her velvety pink suit jacket and skirt, accessorized with a computer, a hat, a briefcase, and a pair of pumps. On the box she was pictured deeply engrossed in her work and handling some bills, but at one and the same time, above the tasteful prescription glasses that made her look smarter, she was throwing secret glances at Ken. Oh, the romantic convolutions that took place between them in that little office overlooking the Twin Towers! In the evening, that selfsame Barbie would slip out of her suit jacket to uncover a shimmery pink bodice; she’d turn her plush skirt inside out to unveil a sequin trim, then put on her open-toed heels, grab her clutch, and head out with Ken to some super-expensive restaurant in Manhattan. Was there anything more perfect than this Barbie? I spent hours upon hours admiring her ability to effortlessly transform from businesswoman to vamp, vamp to businesswoman. The third, Tropical Barbie, was given to me by my uncle Lolo. Her accessories were rather modest, but you had to admit she possessed qualities neither my first nor my second Barbie possessed. Sure, my cousin Karolina from New York had ten Tropicals lying idle in her overseas suitcase, which she habitually left strewn all over Grandma Luca’s house in Privlaka, but against the earthy gray landscape of Sloboština, my Tropical girl was absolutely singular. She had long blonde hair (all the way to her knees), a little Hawaiian swimsuit, and a skirt (imitation flowers). She wasn’t a glam heroine from Dynasty, she wasn’t a businesswoman from Manhattan, she was a beauty of nature—the ocean, the sun, and the waves. Even though that wretched, barefoot soul had only a single hairbrush to her name, Tropical Barbie was unsurpassed as far as her natural attributes were concerned.

From that point, their numbers grew in an orderly fashion. The fourth in my collection was not a Barbie but an Aerobic Skipper—Barbie’s little sister or cousin, whichever you imagined. My parents bought her for me when they went to Rome with my brother, aunt, and cousin. I say “bought,” but they essentially bought me off with the Skipper because there was no room for me in our Renault 4. But hey, being bought off with a Skipper wasn’t all that bad. Aerobic Skipper was almost equally perfect—like Barbie, but of a lower class. They’d initially intended to buy me some pitiful tennis player who only came with a crummy little racket, but since they subsequently decided to stay in Rome a week longer, the gift had to reflect those changes with a significant upgrade. Although Skipper could never be Barbie, because she had smaller boobs and it was anatomically impossible for her to wear heels, anyone with an ounce of dignity had to have at least one Skipper. Obviously, along with a Ken, who was absolutely indispensable, despite the fact that no grander euphoria could be obtained from owning a Ken, given that he merely served as another one of Barbie’s accessories. The heart of the matter is, I’d only seen Aerobic Skipper in the Barbie catalog that I was given free of charge in the American pavilion at the Zagreb Fair and kept in a special folder to protect it from accidental damage. She came with every possible piece of sporting equipment imaginable, from a pair of leggings, some leg warmers, a leotard, and two pairs of sneakers (pink and yellow) to visors, tennis skirts, and tracksuits. But dwelling on excess in Barbie World was itself excessive, because no one—no one—in this world could have an excess of anything from Barbie World. A shortage—yes! A shortage always. Just how much was missing from as modest a Barbie household as mine? Listing the items would take a lifetime—and longer, if you named every single accessory down to the tiniest one, all the pinks and purples on those catalog pages I had spent so many hours staring at in the hope of bringing them to life, in the hope that those pictures would become real, objects I could have and hold.

Ah, those images of Barbie World in those Barbie magazines that turned my longing into immeasurable sorrow. The commercials between segments of Fun Factory that I watched on Sky via satellite. And to think that one Saturday morning, in the very middle of an episode of Fun Factory, my mom and dad had dragged me to a “Passion of the Christ” exhibit where there were hundreds of different crucifixes on display. In that moment, all I wanted, more than anything else in my life, was to set my eyes on the endless combinations of Barbie outfits that the commercials advertised to the beat of “Fun, fun, fun!” Eventually, night would ease my suffering, but every fresh glimpse into that perfect world, elaborated to its teensy and even teensier details, dared to crush my body, in danger of bursting from all those intense longings.

And yet, little by little, you come to terms with your deprivation and begin seeking out other solutions. They were certainly not lacking in my Barbie household, scrapped together as it was with every “other solution” under the sun. Being deprived of the catalog’s offerings had so twisted my mind that I could associate absolutely anything on planet Earth with Barbie: the washbasin my grandmother used to soak her feet in scented salt became a pool for Barbie; cassette holders sitting upright served perfectly as armchairs for Barbie; bricks from the balcony, along with some soil from my mother’s potted plants, functioned as building materials for Barbie hanging gardens; the eraser caps from my mechanical pencils were an adequate set of glasses for Barbie and her friends; perfume samples became top-shelf bottles of whiskey for the cocktail parties Barbie threw (and not so rarely, either); a red Converse All Star transformed into a red Ferrari (one-seater); hand towels were rolled into little beds; aluminum cans lined up together formed a promotional bar for Barbie. The motto of my personal Barbie design was: “Name anything in the world, and I’ll tell you what it can become for Barbie!” Many of the things I made myself with the help of other forced laborers—like my grandmother, who upholstered cardboard armchairs with the purple linen of her old slips, while my mother sewed pillows for them. And unlike the wretched boys’ clothes they sewed for me, my mother and grandmother were perfectly capable of designing sexy-flexy outfits when it came to dressing Barbie. Needless to say, the little outfits they made could never measure up to the originals, but there were some truly brilliant ready-made creations. Of the utmost importance was finding the right fabric—e.g., an old swimsuit made from colorful synthetic material or a curtain that resembled undergarments. The best example in the latter category was, unquestionably, the transparent corset my mother sewed according to a picture in the Barbie catalog. Barbie in that little corset and lying on a bed beside a small nightstand on which she could lay a fake book (she would never read it anyway) next to Ken’s picture (a cutout of Ken’s head glued to a scrap of cardboard)—it was almost a perfect copy of the original scene.

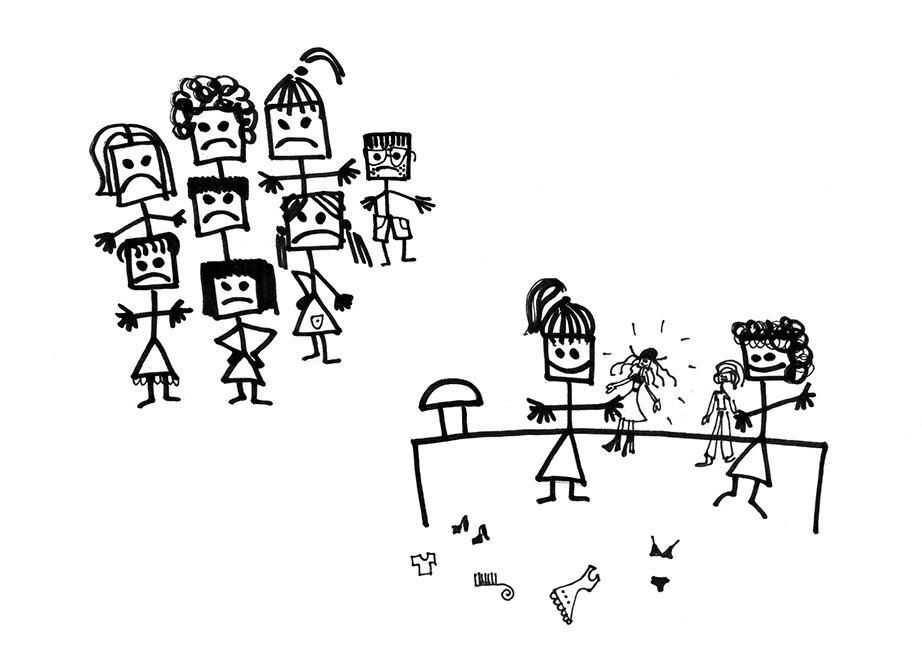

My first genuine pieces of Barbie furniture arrived somewhat later. Closest to genuine, that is. Although Cyndy herself could never be mistaken for Barbie, her furniture, at least, allowed her to act the part. The furniture for Cyndy was cheaper than the furniture for Barbie, so my mother bought me the furniture for Cyndy. First, just a small vanity table with a battery-powered lamp that actually turned on, and then a bed as well. A pink bed with a gold (imitation) vertical-bar headboard. Once, my brother’s friends used miniature handcuffs from a Kinder egg to shackle poor Barbie to that headboard and appointed Ken to do all kinds of abominable things to her. Speaking of Ken, he joined my little Barbie household completely unexpectedly. He came in a bundle package with a brunette wannabe Barbie and two children—all sharing the name of Sweetheart Family. Worse, both of the adults wore engraved wedding rings. I’d only asked my grandmother for a Ken, but Grandma had to go and get me this little holy family set that neither I nor any of my Barbies received with a warm welcome, even though Barbie was by Mattel’s nature an actual sweetheart. That slipper-wearing sissy of a husband was all but glued to his brunette Sweetheart spouse and those two children she had borne for him. They even wore these stupid little matching aprons for the children’s bath time, making an intervention into that humdrum idyll all but necessary. And whenever a blonde Barbie tried to woo Ken, that engraved wedding ring stuck out like a sore thumb. Oh, why couldn’t it have been a removable ring? My grandmother had committed a grave disservice by picking out this set. Now, every relationship between Ken and the blonde Barbies automatically constituted an adultery. What followed this fundamentally unfortunate family was another Skipper—from a duty-free shop in Zadar. I managed to convince my uncle Marko that she was indispensable. She came dressed in a swimsuit that changed colors according to the water temperature. Although the most wondrous bluish color would sweep over her tiny frozen suit, basking in the springs of the so-called mountain-basin sink was not exactly Skipper’s preferred method of relaxation.

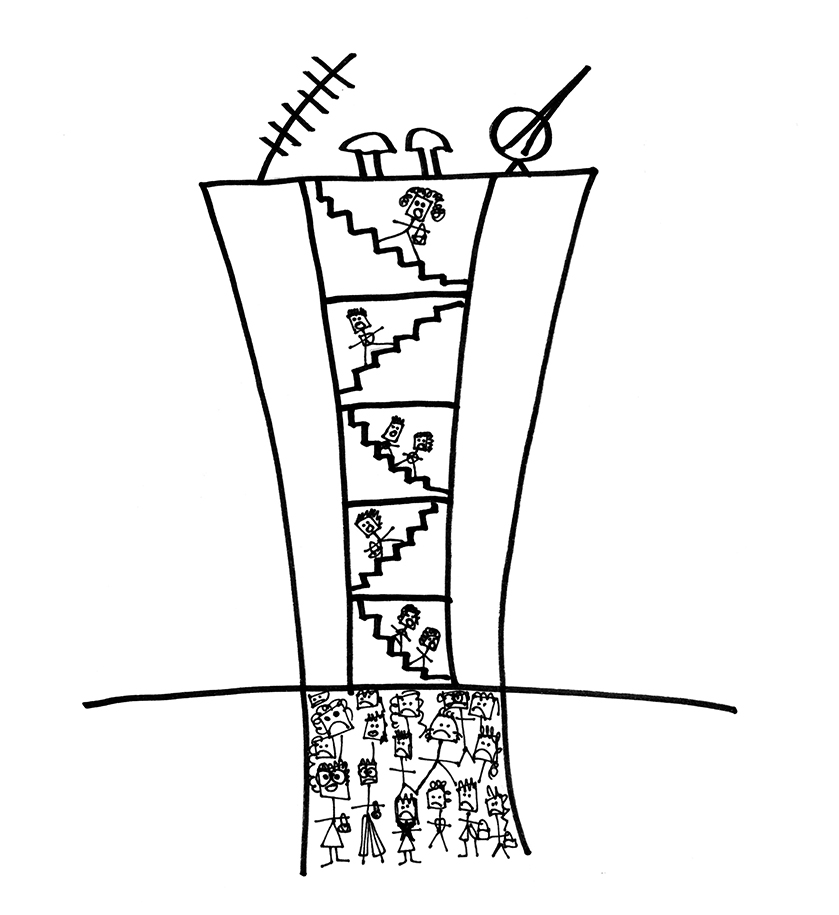

In sum: three Barbies, two Skippers, the adulterous hubby Ken with the brunette Barbie, their two children, a plethora of sewn clothes alongside a handful of genuine pieces, one vanity table, and one bed. That was the full inventory of my initial assets I needed to protect somehow, to secure in the event of a catastrophe, since no personal liability insurance could possibly compensate me were Sloboština to be struck by surface-to-air or air-to-surface missiles, cluster bomblets, machine guns, automatic rifles, assault rifles, bombs, or poison gas. Hence why everything needed to be crammed into my small suitcase. And not simply crammed, but conserved, embalmed in a way against all the dust and shrapnel that might fall upon not only them, but upon all of us. First, each Barbie was individually placed into a plastic bag (the ones my mother used for freezing meat, fish, fruits, and vegetables), then individually wrapped in a towel before then reuniting with all the other Barbies and wannabes in a special canvas bag that was only then stowed in the suitcase. The clothes were stored in a separate baggie, along with a few scented mothballs I stole from my mother’s drawer, and the vanity table was disassembled and returned to its original box. The only problem was the little bed: no amount of mastery in packing could make it conform to the confines of my suitcase. I stormed my brain trying to figure out how best to pack and preserve it, how best to transport this small and exceptionally valuable relic to the catacombs. But, after a lengthy brainstorm and an attempt at compressing the contents of the whole case, the situation with the bed remained unresolved. As a matter of fact, its unresolved status offered a faint glimmer of hope that nothing terrible would actually happen, that no siren or war would come to pass. But they did. The bed situation was resolved ad hoc.

We had to get going to the basement this instant; all the neighbors were already flying down the stairs, and my mother and father were rushing us. As I sprinted toward our apartment door with my suitcase in hand and the little pink bed with its golden frame under my arm, I heard a clap and felt the hot embers on my face. It was a slap from my brother, and the words “Leave that bed, retard!” It was neither the time nor the place for arguing, so I was forced to comply. The little bed was left at the mercy of the Yugoslav National Army. Come what may! We headed down the stairs, and I grew terrified of the planes and of everything that had begun to unfold. The planes continued to hiss past, a little more then, and since I could no longer see them, only hear them, I imagined them as pictures in The Illustrated History of Aviation, in a section called “Warriors of the Sky.”

When we reached the basement, the whole building was already there: Tea, and Dea, and Svjetlana, and Ana P., and Ana Matić, and Borna, and Krešo, and Sanjica, and Marina. Everyone had already landed. I remember that I couldn’t stop crying, and then, after half an hour, the siren stopped and we all headed back to our homes.

That night I slept in my mother and father’s bed. “Slept”? More like: listened intently in case I happened to hear the “steel wings of our army.” And as I finally sank into sleep, Pilot Barbie flew over my thoughts in a pink camouflage suit, streaking the sky a glaring pink in an episode of Fear Factory. Because Barbie could be anything—anything—she wanted. Way more than the catalogs and commercials led you to believe.