From Israel blockading electricity to the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, we live in a moment of infrastructural collapse. Large-scale public works projects have been privatized, meaning that the systems of circulation that enable day-to-day life—from pipelines to data clouds, drinking water to education—are crumbling at increasingly accelerated rates. Now is “a scene shaped by the infrastructural breakdown of modernist practices,” writes Lauren Berlant. Thus, in the political and cultural imaginary, infrastructure has gone from perennial bit player to a starring role.

Not only is political attention to public infrastructure increasing, but also scholarly attention to literary infrastructure. Such work investigates material infrastructure (the object that generates critique) as well as generating a method of critique grounded in infrastructural thinking (investigating how and under what conditions literary critique is produced).

When I say that infrastructure itself is the object of critique, I mean that an increasing number of critics are interested in the literary life of material infrastructures. Books like Julia Lee’s The Racial Railroad and Jessica Hurley’s Infrastructures of Apocalypse, for example, consider how railroads and nuclear power create new narrative logics and literary forms. Lee and Hurley underline how systems and hierarchies are reproduced through the infrastructures that we depend on in our daily lives.

But infrastructure has also become a method for thinking about how and where we produce literary critique. Consider a triumvirate of books published last year: Alexander Manshel’s Writing Backwards, Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction, and Courtney Thorsson’s The Sisterhood. All three are concerned with the infrastructures that produce and circulate literature: Manshel focuses on literary prizes, Sinykin on conglomeration publishing, and Thorsson on how a group of Black writers enshrined their work in the commercial and academic marketplace. Although vastly different in scale and scope, these books share an acute interest in the infrastructures that enable and disable literary production and literary critique.

Manshel, Sinykin, and Thorsson, in other words, think about literary criticism as an infrastructural method. These critics model a way of approaching critique that resembles the function of infrastructure: opening up new ways to analyze individual texts through careful close reading, while also thinking in the abstract and accumulative about how literary scholarship itself enables or disables different types of relationships to infrastructures.

This might be most clearly seen in Thorsson’s work. In The Sisterhood, Thorsson traces how a cadre of Black women scholars in the late ’70s created “a model for collective action to change cultural institutions.” This was a collective enterprise where authors—including June Jordan, Toni Morrison, Ntozake Shang, and Audre Lorde, among others—would cite one another’s work, add readings to syllabi, and nominate one another for literary prizes. The Sisterhood is not interested in the specific representation of infrastructures by any of the authors it discusses (although there is plenty of that too!), but rather with how they created the scholarly conditions to reproduce new types of knowledge outside of institutional path dependency. What Thorsson’s book provides, in other words, is a reading of the work of these authors as an infrastructural method of critique.

Similarly, Anna Kornbluh’s work strives to understand what I describe as this nascent mode of infrastructure-as-method. She is interested in how the novel and studies of the novel produce what she calls “infrastructures of relation to support a world, abstracting from concrete content to produce and limn wholes.” Literary criticism becomes about building and sustaining new relations—whether that is among texts (as in Kornbluh’s work) or among other critics (as in Thorsson’s). Kornbluh continues: “We live in destructive times, on an incinerating planet, over institutional embers, around prodigious redundancy between the plunder of the commons and the compulsive echolalia ‘Burn it all down.’ Theory must prepare to build things up, and literature models that building.”

Actual infrastructures—whether those are universities or bridges—provide the material foundation to perform critique. But infrastructures are not just technical systems. They are also aesthetics and cultural ones that produce very specific articulations of modernity. Thus, Thorsson’s network of like-minded writers and Kornbluh’s call for new ways to approach aesthetic form are both infrastructural.

My argument in this article is that the work of certain authors (including Thorsson, Kornbluh, and others that I detail below) are infrastructuring critique: building new models of critique, which foreground how infrastructure is not just an object of concern, but a methodology for contemporary scholarship. This provides a way for literary critique to intervene into our understanding of those infrastructures. As a literary method of reading, infrastructural critique becomes a practice that seeks to not just offer rejoinders of existing systems, but to actually build and sustain new ones.

I want to spend the rest of this essay thinking through a question that Christopher Breu and Jeffrey R. Di Leo pose in a recent special issue of symplokē dedicated to infrastructure: “Why has the humanities turned toward infrastructure? Why now, after the decimation of the infrastructure of the humanities by neoliberalism?”

Like Breu and Di Leo, my own sense is that a change in institutional headwinds has ushered in a new research environment. The administrative push toward interdisciplinarity, the increasing winnowing of humanities departments, legacy media think pieces on the death of the English major, and the global divestment in humanities funding all indicate a new epoch, where our research faces new crises that are distinctly infrastructural.

This hasn’t gone unnoticed by those of us working in the humanities, especially those in my own discipline of English. Since 2020 alone, there has been a dizzying proliferation of monographs, special issues, and edited collections, all dedicated to the nexus of literature and infrastructure, like some of the ones I list above.

This scholarship builds upon methods that percolated across the social sciences in the preceding decades. In the mid- and late ’90s, anthropologists began turning their attention to infrastructures through the framework of inversion. “Inversion,” as originally coined by Geoffrey Bowker, describes a reorientation of background and foreground, so as to locate and diagram the political and ideological work undertaken by various systems of circulation. Susan Leigh Star began writing ethnographies of infrastructural systems and developing methodologies for engaging with infrastructure, as she phrased it in 1999, “to study boring things.”

This, to return to my earlier point, is a useful way to approach infrastructure as an object of critique. But it’s also a methodology that has limited purchase for literary studies.

Kelly Rich, Nicole Rizzuto, and Susan Zieger summarize this historical trajectory in their introduction to last year’s collection, The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure: “Twenty years ago, a critic could provoke readers merely by claiming that infrastructure was not boring.” This new crop of criticism contends that it isn’t enough to simply make visible the previously invisible (isn’t this, in fact, what literary scholarship has always done?). In fact, those ostensibly invisible infrastructures humming away in the background weren’t actually that boring or invisible anyway, at least not for everyone.

As a literary method of reading, infrastructural critique becomes a practice that seeks to not just offer rejoinders of existing systems, but to actually build and sustain new ones.

My claim is that infrastructural critique in literary studies understands infrastructure not just as object that needs to be brought into the foreground, but also as method. This is a way of understanding infrastructure as an approach to critique: thinking about how the type of critical practices we undertake enable and disable new patterns of circulation.

We can trace this method of infrastructural critique through the prominence of reading across this emergent field. In a 2021 joint special issue of Resilience and American Literature on the topic, “Infrastructures of Emergency,” Reuben Martens and Pieter Vermeulen provide a useful summary of reading infrastructurally: “The critical task is then not simply to make unseen violence visible but to make it readable in relation to social and cultural frames, personal and collective memories and desires, and political and economic forces that impose their own rhythms on what can be felt, intuited, and apprehended.” Their idea is that readability—as opposed to visibility—becomes a political framework: a way to not just identify, but to become actively involved in the process of changing the way we understand ourselves in relation to both one another and the systems that enmesh us.

This charge is taken up in a special issue of Social Text titled (appropriately) “Reading for Infrastructure,” and in The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure. In the latter, the editors’ introduction, “Reading Infrastructure,” provides the most explicit detailing of what this methodology looks like: “First, to read is to place an object in context, attuning oneself to its chronology and setting, to test its narrative against itself. Second, reading trains us to assess the social and political production of infrastructural space, a practice that requires imaginative investigation beyond the visible.”

What is being outlined is a practice of infrastructural close reading. The authors in this collection are interested in very specific infrastructural spaces—roads, dams, borders, etc.—but their practice of reading those object through their aesthetic, political, and cultural dimensions means that they see these infrastructures as a set of contingent relations, ones that are continually open to rearrangement. Infrastructure is not structure. A bridge may look like a static monolith, but it requires continual reproduction by everyone: from the commuters driving on it to the politicians who make the case for funding its maintenance. The act of critique then becomes a place where otherwise relations to existing infrastructure can be imagined.

Take for example Yanie Fecu’s essay on Frantz Fanon and radio in The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure. Fecu traces the complicit role that radio played in perpetuating colonial ideology, but she also looks at how radio was transformed, through creative practice, into an insurgent medium of revolution. She writes that the act of collective listening “generated not only a counterpublic but also a counterinfrastructure that disrupted the cultural, political, and economic circuits of empire.”

What Fecu does is provide a framework for identifying, diagnosing, and (re)interpreting existing infrastructures, alongside the role that critique plays in disrupting and/or sustaining those relations. This is something that Fanon does, but also that Fecu mimics in alerting us to how acoustic infrastructures (e.g., radio) were instrumental as not just telecommunications technologies but also enabled collective practices of rebellion.

Another camp of critics approaches reading infrastructurally through form. In Lee’s The Racial Railroad, for example, she thinks through how the railroad both creates and consolidates “the stories we tell about race in the first place,” while also gesturing toward an insurgent underside where the infrastructure of race is interrogated and critiqued. The train operates as a particularly important example for its continued prominence in the American imaginary as a tool of environmental exploitation and racialization while also being a site of imagined and actual promise and potentiality.

This is true materially: the train, after all, was a place where some of the earliest class and racial struggles took place, thanks to the Pullman porters. But it is also true at a literary level. Lee looks at how Black and Asian writers turn to the train to map the entrenchment of white supremacy and how it becomes instrumental in their critiques. From Anna Julia Cooper to Colson Whitehead, writers continually use the train as a surrogate for their critiques of systemic racism (a topic that has graced the pages of Public Books previously).

This formalist approach draws from the resources and terminologies of genre critique and is equally prevalent in Hurley’s book, Infrastructures of Apocalypse. “Infrastructure is thus produced by narrative forms,” she writes, “and at the same time it also establishes—at least partially—the kinds of narratives that can play out within its space.”

In these accounts, infrastructures are simultaneously produced by and produce narrative. Infrastructure is equally material and metaphorical. And it’s this movement between these two valences of infrastructure in which literary critique thrives.

Looked at in a certain light, ideas around the infrastructural humanities mirror the omnipresence of turns in critical theory (not to mention the en vogue prefixing of the humanities more generally). Whether it is the environmental, material, affective, digital, or … fill in the blank, there has been a proliferation of ostensible novel frameworks for reading in the past few years. In this sense, it’s hard to shake the feeling that literary studies of infrastructure are just another front in the so-called method wars, where competing practitioners make the case for the primacy of their approach to interpretation.

What troubles me about this emphasis on methodology is that we occasionally lose sight of what we are trying to actually do as literary critics. Matt Seybold and his guests across the best-in-class podcast series “Criticism Ltd.” have argued that method has become a substitute for actually thinking through the politics of critique. Much of this work has confused cause and effect. In a recent survey of the method wars, Stacey Margolis drives this home: “One of the strongest critiques of the formalist turn—and, by extension, many of these new methodologies—is that it mistakenly equates passively thinking with actively performing political actions.” Observation is not the same as actually acting.

But the scholarship emerging on infrastructure wants to move past this methodological impasse and to think about how a literary critique of infrastructure can and should produce action. Jeffrey Insko and Jessica Hurley phrase this question concisely in their introduction to American Literature: “If another world is indeed possible, then how can we make it from the infrastructures of the world that we have?”

Infrastructural critique in literary studies understands infrastructure not just as object that needs to be brought into the foreground, but also as method.

Let me give an example of what I mean. In Kornbluh’s most recent book (the genuine academic blockbuster) Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism, she thinks about how to create the infrastructures to support artistic and critical production. She identifies how the contemporary is defined by its prioritization, above all else, of circulation, from binging entire TV shows to Amazon’s next-day delivery. This, of course, is an infrastructural relation, as Brian Larkin wrote back in 2013: “Infrastructures are matter that enable the movement of other matter.” What this means is that the political also becomes infrastructural: the contested site between flow and blockage. Infrastructure, in this iteration, is the metaphor and method for her own critical thinking.

Kornbluh wants to create new infrastructures for producing theory. Sure, an extemporaneous X-thread can come up with an interesting syllabus almost immediately (a genre Kornbluh practically invented), but it doesn’t allow for the structural conditions necessary to perform sustained and ongoing criticism. She argues for the importance to theory of “distance, abstraction, movement away” as opposed to the primacy of immediacy’s “intimacy, immersion, the negation of intercession.” If we are invested in the act of trying to create these metaphorical structures of literary criticism, why wouldn’t we want to figure out how to start building new structures?

Kornbluh concludes by reading Caroline Levine, Sianne Ngai, and Fredric Jameson, describing their collective critical practices as “[committed] to categorical thought, the composition of categories that work for and through scale, impersonality, and hold. They offer interpretation of aesthetics to propound syntheses that can, in turn, capacitate new understandings and other kinds of critical theorizing.”

This, for my money, is an infrastructural critique. She constellates a way of thinking across scales that are named and enabled by and through infrastructure that, in turn, offer the potential space to create new patterns of possibility.

We can trace these patterns in Mark McGurl’s Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon. McGurl takes on the complex infrastructure of Amazon and subjects it to generic critique. He explores how its infrastructural and logistical operations are conditioned through various devices of genre: the romance, the epic, and the novel.

While the specifics of the critique are less important to me, what is telling is the way he thinks through how an actual existing logistical enterprise is materialized and made legible (and, therefore, readable) through the logics of genre. For McGurl, this becomes a way of thinking about how we move past the stranglehold a company like Amazon has on determining the conditions of the contemporary. He writes: “To analyze fictions produced in Amazon’s shadow is hardly sufficient to the task of reconstructing our collective life on more sustainable grounds, but it is one place to start thinking about what it would mean to try.”

McGurl’s final phrase, “to try,” feels like a particularly useful way to summarize infrastructural critique more generally. These scholars are not just thinking, but also trying: modeling new ways of reading and working with texts that might be able to generate new conditions of circulation.

Today, the infrastructure that supports our research and teaching continues to teeter as it is continuously rescripted by administrators, journalists, and popular culture into a moment of forever crisis. As such, we must continue to identify new ways to try and build something different. This reflective glance inward at infrastructure—at what is “beneath, behind, before”—seems like as good a starting place as any.

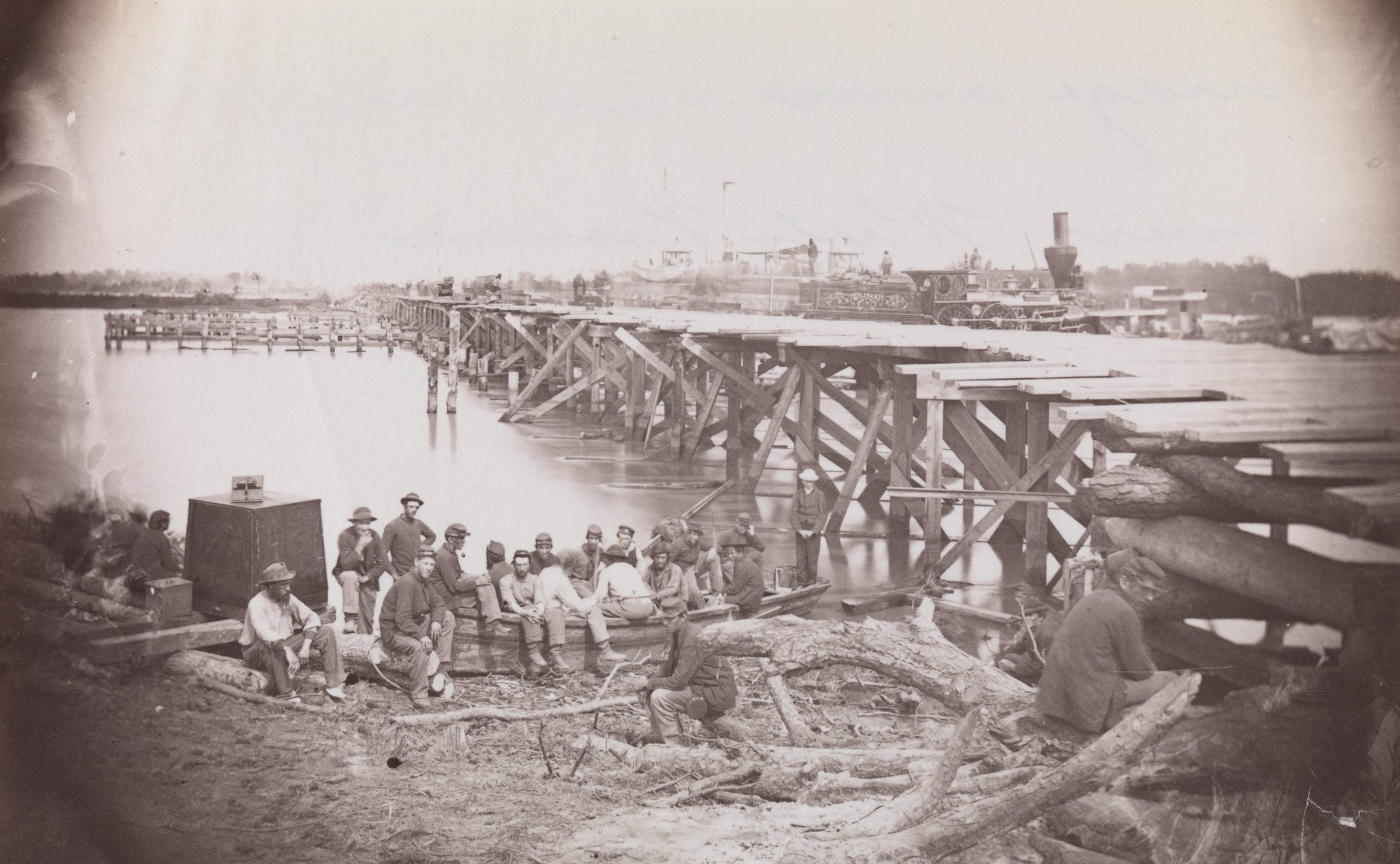

If we want to build new infrastructure, we first must study it. But we can’t stop there. We also need to try to build new ones. ![]()

Featured image: Detail of Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Bridge Across Pamunkey River, near White House (c. 1861–65). Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.