In the first half of the twentieth century, radical bookstores took many forms and often served as part of larger, multichannel campaigns. Nazis, as well as Communists and Socialists, organized festivals and parades, dances and concerts, and schools and camps to disseminate critiques of American democracy and American capitalism. Bookstores served as their intellectual hubs, the places where ideologies circulated—and places granted at least a veneer of respectability.

Article continues after advertisement

Indeed, the Aryan Book Store was much more than a place to buy something. It was the de facto headquarters of American Nazism.

*

The Aryan Book Store opened in March of 1933, the same month Franklin Delano Roosevelt took presidential office and, across the Atlantic, when an Austrian-born, middle-aged antisemite rose to power. Hitler’s message of hate was spun and spread by an elaborate propaganda machine, a machine with its official heart in Germany and limbs stretching across the globe via an army of enablers. The goal was international revolution, a restored German Empire, an earth peopled by an Aryan race.

To win over Americans, they focused on Los Angeles, and Hollywood in particular. Although Nazis were more famous for burning books, they also sold them. Destroying books and establishing bookstores were both a tacit acknowledgment of the same truth: books have power.

The bookstore made no secret of its aims. On the ground floor, it was the most visible part of the South Alvarado Street operation that also featured a restaurant, beer garden, and meeting room. The eating, drinking, socializing, and guest lectures, along with the reading, discussing, and browsing, were all intended to recruit Californians to the Nazi cause.

Although Nazis were more famous for burning books, they also sold them. Destroying books and establishing bookstores were both a tacit acknowledgment of the same truth: books have power.

As the Depression unfolded, curious passersby, including unemployed wanderers, popped in, looked around, and chatted with booksellers, who gave them easy explanations for the root cause of their suffering. Most of the theories fundamentally boiled down to this: the Jews control everything, and the Jews ruin everything.

The store described its specialties as anti-Communism and antisemitism, which it defined as one and the same. One woman remarked that the bookstore “really opened her eyes to the Jewish-Communistic conditions in our country.”

On a typical Friday evening, twenty-five people visited, mostly men in their twenties who drove Pontiacs, Buicks, and Studebakers. We know these details, as well as their plate numbers and the exact times at which they arrived and departed, because just around the corner was a spy.

Although the authorities downplayed the Nazi threat, American Jews did not. The same year that the Aryan Book Store opened, a Jewish lawyer named Leon Lewis established a team of undercover operatives, men and women, Jews and Gentiles, to expose Nazi plots—plots to take over Hollywood and ultimately America.

The then manager, thirty-one-year-old Paul Themlitz, greeted all his customers. “Take a look at this,” he’d say, ushering them over to the latest issue of Liberation, a Fascist newspaper. If they appeared receptive, he invited them into one of the private backroom offices. Here was the nerve center of the Friends of New Germany, a group of pro-Hitler German immigrants.

In his downtime, Themlitz wrote letters to German-owned businesses warning of Jewish boycotts, an obsession of his. He typed the letters on official stationery embossed with the store insignia, a red oval encircling a large swastika.

Themlitz often worked alone but at times employed another bookseller, whom he paid one dollar a week plus room and board. Ideal employees were Americans already familiar with the tenets of Nazism. Mein Kampf was required reading.

The newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, and books, some in En- glish and others in German, didn’t come by way of traditional means. The store was fed by a combination of niche American publishers who printed or reprinted antisemitic tracts and by German steamships that transported works concealed in burlap. Customs officials at the Port of Los Angeles were not a great obstacle. Themlitz gloated (and probably exaggerated) when he claimed that a bit of cash and a bottle of champagne usually did the trick.

German boats also arrived at Pier 86 in Manhattan, where books found their way to the shelves of the Mittermeier Book Store. A member of the Nazi Party, F. X. Mittermeier had a store on East Eighty-Sixth Street. He sold Mein Kampf, Jews Look at You, and The Program of the Party of Hitler.

In preparation for a Madison Square Garden rally of sympathizers, the shop ordered two thousand copies of Nazi Party songbooks. One tune was called “Death to Jews.” There were other Nazi bookshops in Chicago and San Francisco.

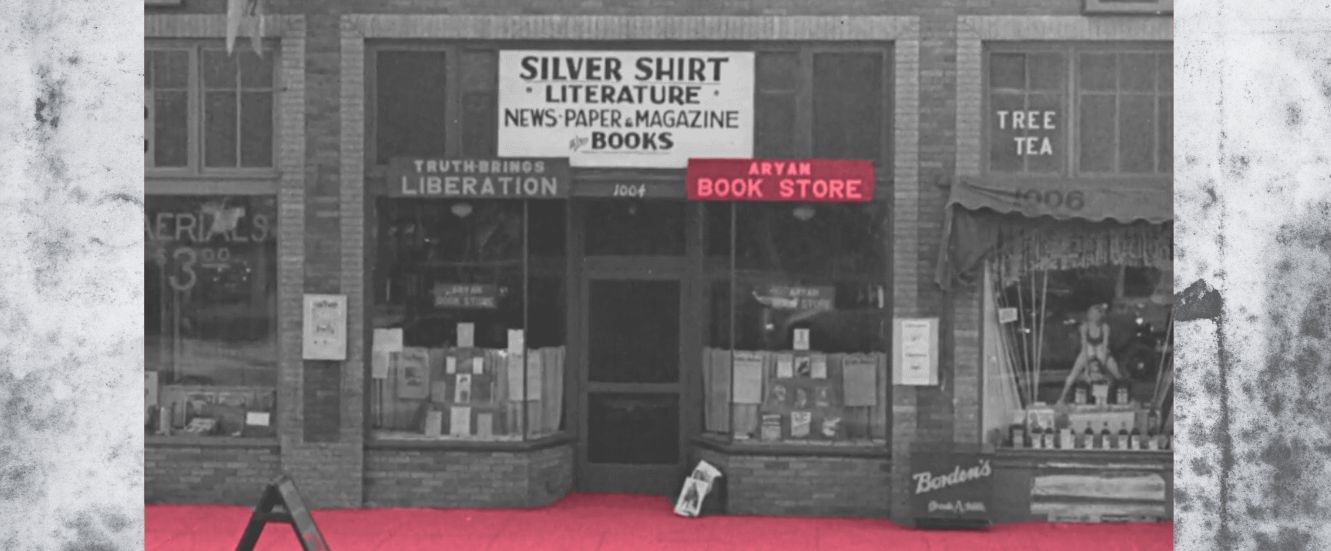

Business at the Aryan Book Store grew brisk enough to warrant a move to a larger location on Washington Boulevard. On the sidewalk was a sandwich board directing the crowds—mostly men, all in suits—inside. A newsboy hawked copies of the Silver Ranger. “Free speech stopped by Jew riot!” he shouted. Above the generous book- store windows were three signs:

ARYAN BOOK STORE

TRUTH BRINGS LIBERATION

SILVER SHIRT LITERATURE

Inside was a decent-sized counter, desk, and center table. The color scheme was green (for hope) and red (for loyalty). Hitler’s speeches played on a phonograph.

A hallway led to a reading room with a generous light well where the regulars gathered. They folded flyers and swapped conspiracy theories. (For example, President Roosevelt was Jewish, and so was the Pope, despite his “Italian name.”) Off the reading room was the office of Hermann Schwinn, the leader of the Friends of New Germany and one of America’s most notorious Nazis. The bookstore was not separate from political organizing.

As spies infiltrated the shop by posing as friendly customers, others resisted out in the open. On two different occasions in 1934, bricks and rocks crashed through the windows. Themlitz blamed the Communists.

Shortly thereafter, Themlitz was called to testify, albeit not about the vandalism. The McCormack-Dickstein Committee, led by Samuel Dickstein, a Jewish New York congressman, was one of several 1930s congressional committees charged with investigating “un-American activities.”

Themlitz didn’t deny carrying antisemitic works. He insisted there was nothing disloyal about it; he was merely sharing “the truth about Germany.” When showed a photograph of two swastika flags in his bookstore, he asked that the record reflect that there was also an American flag just out of view. And he took grave offense at the charge of engaging in any activity considered “un-American,” a term he regarded as being synonymous with Communism.

“If you would go down and look over my windows, you would see—I have quite a few anti-Communistic books in my store,” he added smugly.

Dickstein also grilled F.X. Mittermeier, the bookseller and a dues-paying member of the Nazi Party. “Have you Shakespeare in there?” the congressman prodded. “Have you got Dickens’s works in there?”

Mittermeier said no. It wasn’t that kind of bookstore.

*

What was so disquieting about bookstores? To be sure, bookstores disseminated propaganda and functioned as recruitment centers. Yet the government often overestimated the threat, especially in terms of the number and power of Communists in particular. Indeed, while some politicians painted enemies with a broad brush, lumping together a motley crew of political malcontents under the singular umbrella of radicalism, more often, American Nazis (and their bookstores) were not the primary concern.

At the congressional hearings on Nazi propaganda, that was explicitly acknowledged: “We are just as interested, if not more so, in anti-Communistic matters.” The subsequent and more famous House Un-American Activities Committee hearings focused on Communists.

Indeed, while some politicians painted enemies with a broad brush, lumping together a motley crew of political malcontents under the singular umbrella of radicalism, more often, American Nazis (and their bookstores) were not the primary concern.

Congressmen were alarmed at the rising number of Communist bookstores. By the late 1930s, there were probably close to one hundred in the United States, some managed directly by the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA), which emphasized the importance of reading for “workers to arm themselves with theoretical knowledge as an indispensable weapon in the class struggle.” The organization maintained regional “literature squads,” with books in English, Russian, German, and Yiddish readily available.

Not far from the Aryan Book Store in Los Angeles was a Workers’ Bookshop, one of three Communist shops in the city. Workers’ Bookshops were also in Hartford, Pittsburgh, Toledo, Cleveland, Detroit, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Minneapolis.

There was a Jugoslav Workers’ Bookshop and three others in Chicago (one not far from Marshall Field & Company). In New York in the mid-1930s, there was a Workers’ Bookshop in the Bronx, another in Yonkers, two in Brooklyn, and four in Manhattan, including the most prominent of all on the main floor (turn left) of a nine-story building on East Thirteenth Street.

Originally opened in 1927 along Union Square, the Manhattan store had long rows of books spanning theory, “proletarian novels,” children’s literature, Soviet culture, the arts, unionism, imperialism, and capitalism. If there was such a thing as a radical neighborhood, this was it. It was home to the CPUSA offices, the headquarters of the New Masses, and the site of annual May Day parades.

It was also home to Socialists, namely the Rand School Book Store, the most prominent Socialist bookshop in America. The Rand School of Social Science opened in 1906. With appalling income inequality, unsafe working conditions, and no genuine welfare state, Americans were increasingly turning to Socialism.

In 1912, Socialist Eugene Debs ran for president, netting more than nine hundred thousand votes. This was before the Great War. Before Socialism became so scary. Before Debs was thrown in jail.

The Rand School was the educational nucleus of the movement, offering courses on the history and theory of Socialism, composition, and public speaking, as well as a Sunday school for kids. Leading thinkers, writers, activists, and authors, Socialists or otherwise, taught classes and gave evening lectures, including W.E.B. Du Bois, William Butler Yeats, Jack London, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Carl Sandburg, Bertrand Russell, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Upton Sinclair, Clarence Darrow, Helen Keller, John Dewey, H.G. Wells, and Diego Rivera.

By 1918, more than five thousand students, mostly workers in their twenties, many of them Jewish immigrants, attended class in the People’s House, a handsome building of chunky brownstone and bricks with its name emblazoned in oversize letters on the fifth story. Anyone walking by on East Fifteenth Street between Fifth Avenue and Union Square, just a few turns from Book Row, couldn’t miss the archway-framed line of windows. Inside were stacks of books and magazines, newspapers and pamphlets, and bulletin boards tacked with flyers.

Although it sold texts to students, the Rand was more than a school bookstore. It was a hangout with a cooperative restaurant in the same building. While other bookshops struggled to attract laborers (“We never really reached working people,” lamented the Sunwise Turn’s booksellers), the Rand did—and made money doing so.

Over the 1918–1919 academic year, it totaled more than $50,000 in sales, far more than the average bookstore. People ordered by mail from around the country, and customers with no Rand affiliation leafed through the store’s selection of alternative newspapers and magazines—The New York Communist, The Workers’ World, and Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review. There flourished a wide range of pamphlets and books, some published by the store itself, including editions of The Communist Manifesto, Women of the Future, and The Salaried Man.

In June of 1919, state officials launched a raid on New York organizations suspected of plotting to overthrow the government. Fifty officers marching in pairs ransacked the Rand School’s bookstore, carting away boxes of books deep into the night. The New York Times cheered, labeling the Rand a brainwashing center that fomented “hatred.” New York’s attorney general promised to shut down the bookstore for good on the grounds of having distributed “the reddest kind of red propaganda” and, worse, radicalizing “the negroes.”

Under the National Recovery Administration, the government had finally given publishers and the American Booksellers Association what they had long been lobbying for (and what the Supreme Court had previously denied): legislation forbidding booksellers from discounting.

The Rand School’s attorney, who worked pro bono and self-identified as anti-Socialist, argued that the bookstore sold thousands of titles, including classics that had nothing to do with Socialism. “The New York Public Library and probably every other great public library and book store has on its shelves hundreds of books of the character you condemn,” he wrote. “Why not seize their property and blow open their safes?”

He charged the state with “frittering away” time and money by “unearthing” books openly displayed in the wide windows, printed in catalogs, and advertised in newspapers.

With factions pulling in opposite directions, the Socialist Party of America splintered in 1919, leading to the formation of the CPUSA. Communism grew as the Socialist Party—and Socialist bookstores— began to fade. By the mid-1930s, the Rand School Book Store, which had once helped fund the school, had only about $8,000 in yearly sales, compared with the more than $50,000 of two decades prior. The small expenses—telephone, towels, stationery, window cleaning— added up. The store was bleeding money.

Two blocks south, the Workers’ Bookshop increasingly became a destination. It hosted reading groups, exhibitions on the history of Marxism, and a circulating library where party members borrowed books for fifteen cents a week. Pro-Communist gear was on sale, too. Show your support for the cause, shop staff urged, with an anti-Hearst button or a progressive greeting card.

The shop offered periodic sales to workers (available at any Workers’ Bookshop nationwide), distributed leaflets, issued a regular newsletter, and sold tickets to balls, dances, and talks by Emma Goldman. It was a physical hub where anyone could read endlessly about Communism and meet real Communists.

The Workers’ Bookshop also stocked anti-Nazi works. Among them was The Brown Book of the Hitler Terror, which alleged that the Nazi government was responsible for burning down the Reichstag, home of the German Parliament.

In 1934, A.B. Campbell found it on the shelf. He was alarmed. It wasn’t the content. The price was too low. Under the National Recovery Administration, the government had finally given publishers and the American Booksellers Association what they had long been lobbying for (and what the Supreme Court had previously denied): legislation forbidding booksellers from discounting.

The Roosevelt administration concurred that price-cutting “oppressed small independent booksellers.” The new Booksellers’ Code required books to be priced, for at least the first six months after publication, at the publishers’ list prices. A nine-person National Booksellers’ Code Authority was charged with oversight. In reality, the ABA handled most of the complaints.

As it turned out, the charge against the Workers’ Bookshop derived from a tip from someone at Macy’s, the very target of the federal legislation. The Daily Worker called the department store “one of the most notorious price-cutters, when it comes to selling publishers’ garbage.” Ultimately, the case was dropped, and the Booksellers’ Code lasted for just over a year. At that point, the Supreme Court struck it down once again, deeming the NRA unconstitutional.

______________________________

The Bookshop: A History of the American Bookstore by Evan Friss is available via Viking.