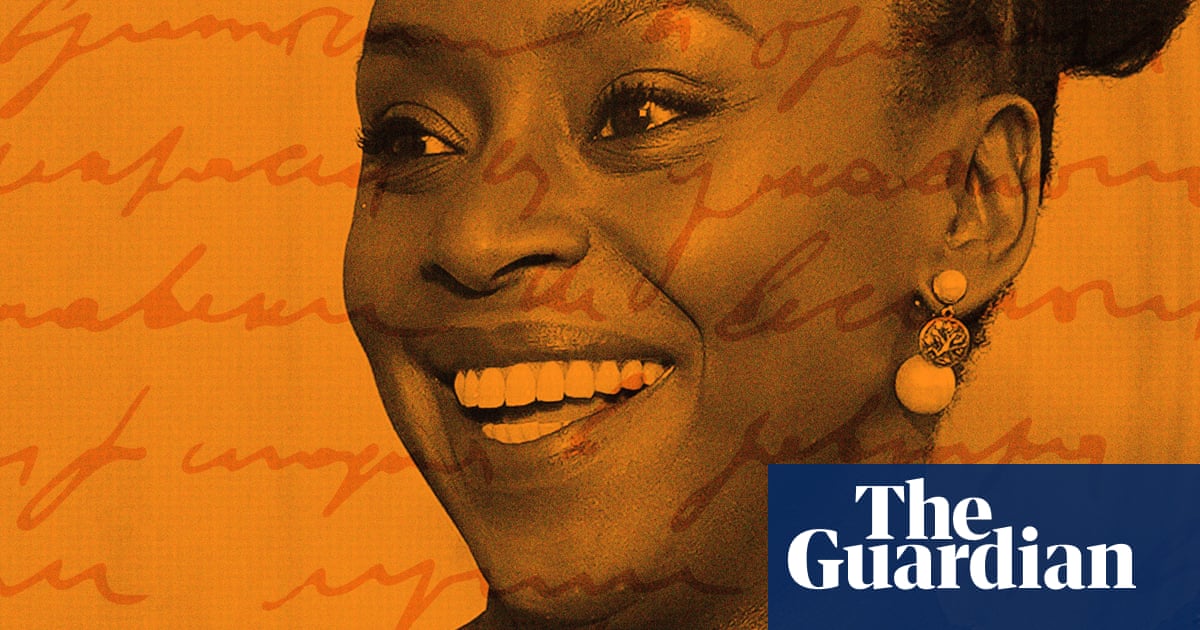

She’s won multiple awards for her novels, had her Ted talk sampled by Beyoncé, and was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People of 2015. Now, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is back with her first novel in 10 years – so if you haven’t read anything by the Nigerian author yet, it’s a good time to catch up. Writer and critic Maya Jaggi suggests some good ways in.

The entry point

Adichie’s second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, not only won the Orange prize for fiction (now the Women’s prize for fiction) in the year I was a judge, but also its Winner of Winners in 2020, and was made into a 2013 film with Chiwetel Ejiofor and Thandiwe Newton. It begins after Nigerian independence in 1960, telling the story of the Biafran war via “The Master,” a maths lecturer in Nsukka (where Adichie grew up), his London-educated lover Olanna, and teenage houseboy Ugwu. The traumas of war are preceded by joyous intellectual jousting, fuelled by Ugwu’s mouthwatering jollof rice and pepper soup. While Adichie once acknowledged to me her debt to Romesh Gunesekera’s Sri Lanka-set novel Reef for this master chef culinary device, her breakthrough novel earns its place as a west African War and Peace.

The credo

Adichie’s essay The Danger of a Single Story, first given as a 2009 Ted talk (and available as an ebook), sets out her stall as a storyteller as succinctly as Orwell’s 1946 essay Why I Write. Joining novelist Chinua Achebe’s call for a “balance of stories,” it echoes Binyavanga Wainaina’s How to Write About Africa, the 2005 satirical bombshell in Granta magazine – reprinted in a posthumous 2022 collection for which his bereft friend Adichie wrote the introduction. “Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story,” she writes – a flattening of experience that “robs people” of human complexity and dignity while exaggerating their differences. “Africa is a continent full of catastrophes … But there are other stories … just as important.”

The spectacular debut

The consummate coming-of-age novel Purple Hibiscus, which won the Commonwealth Writers’ prize for the best first book, explores faith, freedom, sexual awakening and religious hypocrisy through a 15-year-old girl, Kambili, growing up in south-eastern Nigeria after a military coup. Her father, a “Big Man” factory owner, is a patriarch and religious zealot whose wife-beating tyranny devastates the family, even as he garners human rights awards for defying the new regime. Where the Catholic church demands prayer in Latin not Igbo, and cash-stuffed envelopes get things done, a brother’s act of defiance leads ultimately to prison. Yet Kambili blossoms with a scholarly aunt in Nsukka, a university town where questioning and debate are encouraged not slapped down. To the strains of Fela Kuti, she exults because, for all its potholes, “Nsukka could free something deep inside your belly that would rise up … and come out as a freedom song.”

after newsletter promotion

The epic love story

The 600-page, tricontinental novel Americanah, winner of the US National Book Critics Circle award for fiction, is as much sharp observational comedy and critique as romance. Its heroine Ifemelu, a fellow at Princeton, is first seen having her hair braided for the journey home after 13 years away. Fleeing military-ruled Nigeria, she felt the burden and pathologies of race only in the US – as explored in her flâneur’s blog, “Raceteenth, or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known As Negroes) by a Non-American Black”, which ranges from Barack Obama to the vexed politics of black hair. But her homesickness is partly for her first love, Obinze, the “only person with whom she has never felt the need to explain herself”. Having failed in the visa lottery for the Land of the Free, he languished in London before making it as a property developer in his newly democratic homeland. As the novel traces their sundered lives towards reunion, the question is whether their love is beyond rekindling.

****

The one everyone should read

We Should All Be Feminists speaks to successive generations of women and men in its efforts to reclaim feminism’s high ground from a mighty backlash. Expanded from a 2012 Ted talk – since sampled on Beyoncé’s Flawless – it bristles with outraged anecdotes and observations on how women are still taught to shrink and silence themselves, how gender bias becomes normalised through repetition, and how the cage of masculinity breeds men’s fear of weakness and vulnerability. “We must raise our daughters differently. We must also raise our sons differently,” Adichie writes in a book that could be read alongside her advice for parents, Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions. Embracing her great-grandmother, who ran off to marry the man of her choice, as a feminist avant la lettre, Adichie rebuts notions of feminism as “unAfrican”.

The one that will make you feel less alone

Published the year after her father’s sudden death from kidney failure, Notes on Grief is a doting daughter’s reckoning with her father’s loss. It contains rare confidences from an author who guards her privacy, and a bracing confession of the rage and turmoil of mourning. Though the family met on Zoom, Adichie had not seen her father in the flesh for months when he died during lockdown, and her “leaden heart” feels only fury at condolers’ presumptuousness (“he is in a better place”). Flashes of obituary reveal a man, deputy vice-chancellor of the University of Nigeria in the 1980s and a leading professor of statistics, who had returned from doctoral studies at Berkeley shortly before the Biafran war, when all his books were burned by Nigerian soldiers. Years later, he was kidnapped for ransom because of his famous daughter. Yet his humour, “already dry, crisped deliciously as he aged”. Was he “the reason I have never been afraid of the disapproval of men?” Adichie asks. “I think so.”

The comeback

Her first novel in 10 years, Dream Count, charts the interlinked lives and desires of four women during the Covid-19 pandemic. Adichie’s mother, who died in 2021, was an inspiration for its mother-daughter relationships. Central is Chiamaka, a Nigerian travel writer living in the US, considering her body clock and missed opportunities. The character of Chiamaka’s housekeeper, Kadiatou, was inspired by Nafissatou Diallo, the Guinean woman who in 2011 accused the then IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn of sexual assault in the New York hotel where she worked as a maid – though the case was dismissed because she was said to have lied about her background. “A victim need not be perfect to be deserving of justice,” Adichie notes in the novel’s afterword, arguing for the need for “imaginative retellings”. Fleshing out this character while preserving as sacrosanct her account of the alleged assault, was, for Adichie, “to ‘write’ a wrong in the balance of stories”.