John William De Forest’s Miss Ravenel’s Conversion from Session to Loyalty might not have been the “Great American Novel,” but its author was the first who conceived of their being such a thing. In 1868, while writing in The Nation, Deforest called for the creation of a new type of literature, of a novel that could “paint the American soul,” which would “capture the ordinary emotions and manners of American existence.”

Article continues after advertisement

Literature as Manifest Destiny, commensurate with the American continent stretching from New York Harbor to San Francisco Bay; literature which sutured the nation together as surely as Civil War transformed these united states into The United States. An imagined and idealized book that included the teeming multitude working on the factory floors and the boardrooms of the capitalists, the settlers of generations immemorial and the immigrants arriving at port, the rusticated farmer and the president of the United States.

The [Great American Novel] is a manifestly strange idea, the fabulism that a single author in a single novel can somehow encompass the entirety of a country.

A walrus-mustachioed Union Captain in the 12th Connecticut Volunteers who’d served in Louisiana and the Shenandoah Valley, the Nutmegger had lived in not just South Carolina, but briefly in Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine as well, and so De Forest imagined a maturing American literature taking its place in the world as he had. “We may be confident that the Great American Poem will not be written,” De Forest wrote, for the age of Homer and Virgil, Tasso and Aristo, Spenser and Milton, was too antiquated for such a young nation, but “the Great American Novel…will, we suppose, be possible.”

Because the novel itself is a young form, it was to be the appropriate method of expressing the nation. Any number of candidates for the Great American novel (henceforth “GAN”) have been proffered, works as antiquated as James Fennimore Cooper’s 1826 The Last of the Mohicans to contemporary door-stoppers such as Jonathan Franzen’s 2001 The Corrections, but any broad agreement on which of these is the singular example is as elusive as Ahab’s white whale.

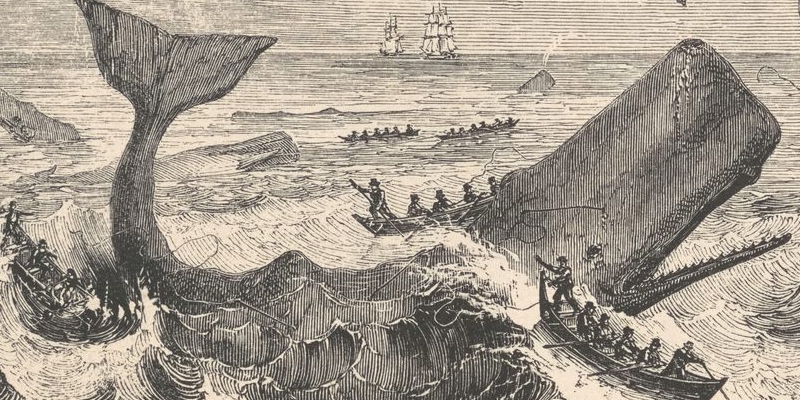

Herman Melville’s 1851 Moby-Dick from whence I drew that last metaphor is often configured as an example of the GAN, as is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s slender The Great Gatsby, published a century ago this month. Another pertinent metaphor can be drawn from Fitzgerald, when he writes that “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther.” An apt encapsulation of the GAN itself, for the green light upon Daisy Buchanan’s pier is symbolic of that American desire for more, the same desire behind the fantasy of a novel that can encompass the entirety of the nation.

This is what unifies all of the various claimants to GAN-hood: the sheer hubris of the endeavor, of this idea that we only need reach out our arms further and further and some book will be written one day that’s equivalent with the country, that reconciles all of the contradictions that have long threatened to demolish it, which can restore the nation in a simple act of composition and editing, so as to approach the “fresh, green breast of the new world,” as Fitzgerald wrote, our desire to face “something commensurate to… wonder.”

In defense of De Forest, he never designated his own book as such; as a critic, he doubted that the GAN had been written yet. Throughout his brief note in The Nation, he considers possible claimants to the designation, only to dismiss them. Washington Irving, that old Knickerbocker, may have been the first domestic author to be appreciated by Europeans, but he looked too much to the Old World to be considered authentically American. Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose 1850 The Scarlet Letter is often given as an example of the GAN, is celebrated as the “greatest of American imaginations,” yet dismissed as parochially of New England. If anything, De Forest’s patriotic call evidences an anxiety over our cultural belatedness and lack of seriousness.

After all, it was in 1820 that Sydney Smyth in The Edinburgh Review opined that “Literature the Americans have none… It is all imported.” As such, the GAN was an answer to that charge, but also (as is clear in reading De Forest) an acknowledgement of Smyth’s accuracy as well, for The Nation essay was not celebratory, but imploring.

There is no pining for the Great Belgian Novel, no desire for the Great Fijian Novel, because writers in those nations are simply intent to produce Belgian titles and Fijian books. By contrast, the GAN is a manifestly strange idea, the fabulism that a single author in a single novel can somehow encompass the entirety of a country. America alone among countries has quixotically embraced such a concept. Ironic, for American literature itself, which is largely produced in English, rather than a language called “American,” is itself a misnomer.

The idea of the GAN makes little sense, since in terms of genre American literature should be subsumed into the broader category of Anglophone. After all, the twentieth-century Czech author Franz Kafka is considered a German writer because that’s the language he wrote in, while the eighteenth-century Swiss philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau is taught in French classes because that was his mother tongue.

Yet for critics of De Forest’s generation, language was a secondary issue in defining America and the writing which it produced. “American independence required a distinct literature as well as a separate politics,” notes William Spengemann in A New World of Words: Redefining Early American Literature. Nobody classifies Whitman or Emily Dickinson as English, however, and that’s because it’s not how American critics have conceived of our national literature, preferring to identify something otherworldly, almost mystical, in the land itself, and with the books that would grow from its fertile soil.

Like Utopia or God—or the nation itself—the Great American Novel is a prophetic ideal that we must not abandon.

Lawrence Buell in The Dream of the Great American Novel explains that “one common talk about ‘great’ or defining ‘national’ novels has been cultural legitimation anxiety.” The GAN then was a kind of Declaration of Independence from European antecedents. Though Buell does detect an equivalent desire in that other continent-sized nation of Australia. Which is to say that neurosis wasn’t the only justification for De Forest’s idea.

A feeling of “sheer territorial bulk” was part of the impetus of the GAN explains Buell, the “sense of national bigness.” To patriotic anxiety and geographic size, Buell adds other “American” characteristics which he sees underlining the idea, including the ambiguities inherent in our national character (so aptly explored through the negative capability of the novel), a sense of individualism (exemplified in the form of the novel itself), and an obsession with the future.

According to De Forest, only Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin came close to embodying the principles he envisioned, but that doesn’t mean that there haven’t been veritable shelves of contenders identified since the critic’s essay appeared. Such titles often have a sense of massive scope in keeping with the country’s size, but the relatively provincial setting of Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter or Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn belies that.

Nor should it be said that America itself need be the setting, for despite the early Nantucket chapters of Melville’s Moby-Dick, that consummate GAN takes place in waters entirely international. A large cast of characters is often a prerequisite for GAN-status, as in the multinational crew of Melville’s ship the Pequod, but the focused first-person narration of a Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye shows how granular some claimants can be.

Annoyingly, most of the novels bestowed with such laurels are by white men, but the identification of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man as an example helps to rectify that injustice a bit, as does the not infrequent categorization of Gertrude Stein’s The Americans or Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Finally, the most salient aspect of the “Great” in “Great American Novel” in the form of sheer size need not be an impediment, for The Great Gatsby is maybe the book most commonly identified as such, and it comes in under 200 pages, easily readable in a single sitting.

For a certain type of writer, the Great American Novel represents a literary Mount Denali to scale. Norman Mailer—pugilist, narcissist, writer—was intoxicated by the idea of the “Big Book,” as he called it, drawn to the completism of the endeavor like a Serengeti game-hunter, while Philip Roth even had the semi-ironic chutzpah to dispense with any ambiguity when titling a 1973 contribution The Great American Novel.

The masculinist bravado of such attempts has dissipated over the past five decades as the canon itself has expanded, however; using Google’s Ngram, a cursory analysis of instances of the word across the bulk of published material from the last century shows a peak around 1900 (the era of Henry James and Edith Wharton), again in 1926 (Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, and William Faulkner), in the 1970s (Saul Bellow, Roth, Mailer), and ironically in 2013 right before the idea of America itself seemed to become obsolete, after which there is a precipitous decline in mentions. If America is supposed to be great again, our literary sense of self certainly isn’t.

Which raises the question: what use is the idea of the Great American Novel—that bloated, often sexist, frequently racist, normally egocentric concept—at precisely the moment that our nation seems so clearly in decline, when the country itself is as frayed and beaten as a once-loved paperback that hasn’t been checked out in decades? More than any other country, the United States is a child of textuality. Defined into existence by acts of writing—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution—the United States has always been marked by a literary characteristic at odds with our otherwise deserved reputation for anti-intellectualism. Marked not by blood or soil, the United States is most of all an agreement, a covenant. But nothing makes greater drama than a promise betrayed.

The best of the American literary tradition has to exist in the yawning disjunct between the national ideals as expressed in the nation’s founding documents and the dismal reality of the country itself. Morrison’s Beloved, Ellison’s Invisible Man, these are works which call the nation to account. They are prophetic—they are jeremiads, that most venerable of American literary forms. Mailer in The Armies of the Night, his nonfiction account of a 1967 anti-Vietnam War protest at the Pentagon, arguably much closer to being a GAN than any of his actual novels, prophesied a future choice whereby America, due to its unique history, can either birth the “most fearsome totalitarianism the world has ever known” or rather deliver a “new world brave and tender, artful and wild.”

When would we be more in need of the Great American Novel, or maybe a whole host of great American novels, than now, when we’re faced precisely with that choice? Like Utopia or God—or the nation itself—the Great American Novel is a prophetic ideal that we must not abandon; a means of measuring the height of our imagination and the failure of our reality, a concept that we ever orient ourselves, our boats against the current, born back ceaselessly into the past but staring ever hopefully towards the future.