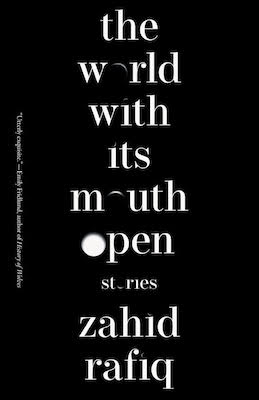

Zahid Rafiq’s debut collection The World With Its Mouth Open carries a quiet sense of haunting. Eleven stories bring forth eleven lives, changed by an encounter—with a stranger, personal grief, financial circumstances or the conflict that stains the quotidian conditions in Kashmir.

In the opening story, Nusrat, a pregnant woman, encounters a childhood friend’s older brother, Rajaji, on her way back from the doctor’s appointment and finds herself grieving the girl she used to be. In “The House,” a workman discovers bones as he digs the earth to build the foundation of a new house. He worries about other secrets the earth holds, insisting to dig deeper, and bringing up questions of how to dispose of the remains correctly but the owners have other plans, adamant on making the remnants disappear without the word getting out. In “The Man with the Suitcase,” Salim, a young man on the hunt for a new job is going door to door at local businesses when he catches a glimpse of a stranger with a suitcase. An unknown curiosity makes Salim abandon his employment search and with it, skirting the responsibilities of being the breadwinner and the grief of having lost his older brother, as he goes on a seemingly wild goose chase. Rafiq offers chilling, striking details that expose his characters’ inner turmoil amid the chaos and violence that permeates their land and lives.

In conversation, on a Saturday morning, Zahid tells me he is a reluctant writer—always avoiding getting to the page but pushed to contend with fear and the uncertainty of life when the words arrive. We spoke about restraint in language, vague endings, the uncertainty of our lives, and more.

Bareerah Ghani: I want to begin with the opening story where we meet this pregnant woman who is grieving her previous miscarriages, thinking about how at the time of losing the baby, she’d begun noticing other childless women. It got me thinking about how sometimes loss and grief, instead of making us more isolated, can make us more attuned to the world around us. I would love your thoughts on how grief affects our worldview.

Zahid Rafiq: I think it is different for different people. Some people, I guess, could become bitter. Some people sharpen. Some people become more aware and receptive of the grief of others. Some probably drown in their grief in a way that they no longer are aware of other people’s grief. I wouldn’t like to generalize. As a writer, I am interested in trying to see who these characters are. How do they respond to grief? What does it make of them? How do they relate to themselves and to one another?

BG: In many of your stories, grief is such a prominent thing, and I wonder if you perceive it as one of those emotions that can consume you, that can quite easily become your identity.

ZR: In cultures where there has been a lot of violence, where there is oppression, injustice, grief, sorrow, kind of, become the sea we swim in. It becomes almost like this nature of ours. We go about life, but grief is this ever-present thing – grief, sorrow, melancholy, the bitter aftertaste of things! And in the place these stories are set in, there is a persistence of grief.

BG: And it shows up in your prose, too, in the way there is restraint. Was that intentional?

ZR: To some degree. I would say it was a restraint I wanted to have in life, and it was a restraint I wanted to have in the prose as well. It was partly conscious, or rather, I became conscious of this while working on it, that I’m trying to hold myself back. I realized during the writing that I was reluctant to take certain paths; I think that the reluctance and the restraint are somehow related.

BG: Your stories have this underlying sense of unease and unrest. They often end in very vague ways, and you leave the reader with a lot to figure out on their own, which I love! I’m curious about how you think of endings in life and in fiction?

ZR: In a way, there are no endings. It keeps going on – something comes to an end, and another thing sprouts out of it. But of course there are, at the same time, endings to stories, to relationships, to everything but they are never very clean endings. Like revolutions end, dictatorships end, countries are born, occupations end, but it always merges into something else. There is this constant metamorphosis that keeps happening, so endings are not very clean to me, not clear to me. And the way I write, sometimes I don’t have the endings. But what I want to do is not write a false sentence. I would rather have it end in a manner that isn’t clean. But at least it is true to itself. The sentence is true to itself, and to the story.

And then, some of these endings are also vague because the world I write about is vague and I don’t quite see it all. I’m trying to make sense of it, just as a reader would when reading the book. And in a lot of places, I am aware of the narrowness of my own vision, of how I couldn’t see beyond something, but that was my limitation as I was writing this book. That was where I was.

BG: I understand what you’re saying about this world that your characters inhabit, which is so uncertain, and I couldn’t help but notice that in so many of your stories we have this presence of a stranger, who your characters encounter, and it changes their day or their life in some way. For example, in “The Man with the Suitcase,” the engine of the story is really just, Salim being curious about this stranger he sees on the street and it leads him to confront his grief, and this suggests to me that our lives are a chain reaction to one another and the world around us. Do you believe life in its essence is uncertain and unstable, and we, in our search of material markers of achievement, create a false sense of certainty?

ZR: It’s extremely uncertain. We cover it up with things, with marriages, relationships, decency, morals, ethics, religion, all of it. But you peel off a layer, and it’s scary, the sheer uncertainty that one might not exist tomorrow morning. In certain places, though, one does not have to confront that fact so much, because the layer that covers this uncertainty is smoother, thicker, unblemished. But if you inhabit places which are, in some sense, saturated in violence, then it becomes very clear how fragile one’s existence is, and how fragile everything is. I’m interested in removing the top layer and seeing how does one live when we know that we can die in the evening.

BG: Did you start writing fiction to contend with this uncertainty?

ZR: I don’t know. That’s a hard question, because I wanted to write fiction for a long, long time. It is some kind of a necessity, that I’m aware of. This is in a way my central meaning.

BG: What is the one lesson you’ve acquired from your years of journalism, and applied in your approach to fiction?

ZR: I think some of the restraint that you spoke about earlier comes from there. One of the necessities of doing that job was not to indulge one’s feelings too much, to go out and report. It’s like, you go to these places where terrible things have happened, and you can’t be the first one to cry. And so that forces on you a certain kind of restraint. You must do your work, you must not weep. That job also introduced me to a lot of people, had me see the various layers of the world in which these stories are set, the world from which I write.

BG: I want to talk about the title. It’s beautiful, haunting, and very apt for the stories we get. There’s this undercurrent of paranoia about the world coming to get you. Your characters are constantly battling expectations and anxious thoughts about what others think and how they perceive them. And there’s always that underlying threat that something bad is going to happen, and it makes sense given where they live. I am curious about where you see the line between this being a cynical worldview or a reality, particularly for those living under occupation.

ZR: I would be curious to see how it speaks to someone who lives in a different set of circumstances. I write out of this mass of feeling, of uncertainty, precariousness, fear of confronting these moments when one is asked to show courage, and sometimes one has it, and sometimes one doesn’t. Before writing these stories, I didn’t know them. To be able to expound on them, to be able to say, what does it mean? I don’t know. I don’t think I have the necessary tools to, or even the vision to say much more. And I hope that if there is more to say, it will take another form of another story, because that’s how I want to think. That’s how I like to think – to articulate myself through characters, through brief moments, sentences.

The title came after the book was done. I didn’t want to take a title from one of the stories. It does in some way capture something of this book, that there is something that can swallow these people. They live around a vortex. Sometimes it’s the vortex of doubt. Sometimes it’s the suspicion, not being able to trust another person.

BG: I was particularly taken by the ending for “Dogs,” where the old dog says to the younger one, “Do you think everyone dies the same way? You don’t still think it is those wretched hiccups and the closing of eyes… if only dying were so easy.” It reminded me of Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha’s verses, “If you live in Gaza, you die several times.” I’m curious about your interpretation of death and dying, and your thoughts particularly on the dialogue?

ZR: I didn’t really decide on that dialogue. For a lot of these dialogues that the characters in the book say, I would like to believe that it’s their dialogue. I didn’t plan that this character will say this.

Characters said their own things, in some way. So when the old dog says what it did, I was like, Okay, what do you mean, old dog? You want to say anything more about it? But the old dog didn’t say anything more about it. And that’s the truth. And for a while I felt the story was incomplete. And had a few endings in mind but all of them seemed like me trying to make sense of the old dog and the situation and the story, and I was like, I don’t want to do that. That’s where it kind of ended for me.

I’m often not convinced by my own endings to be honest, but I think they’re true. I would like some endings in the traditional sense, endings that tie everything together. Till that happens I guess I am stuck with incomplete, unsatisfying, truths.

BG: I understand where you’re coming from. It does feel organic in your writing as well. It’s one of the things I really liked about this book. The fact that we end kind of mid event.

ZR: And these people, these characters, these dogs – they’re going to continue their life. They’re going to continue with their day. And we just have a sense of these characters. That’s how it is for me.

BG: What is next for you in terms of writing fiction?

ZR: I think another story, probably a novel. I’m hoping a novel. I’m trying to write it but it is this distant cloud of dust that has in it shapes, faces, that has a mood, and I’m trying to get a feel of it, not in the way that I understand it, but in the way that I can speak it and go farther, go closer.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.